- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Deployable Structures

About this book

Deployable structures can expand and contract due to their geometrical, material and mechanical properties – offering the potential to create truly transforming environments. This book looks at the cutting edge of the subject, examining the different types of deployable structures and numerous design approaches.

Filled with photographs, models, drawings and diagrams, Deployable Structures is packed with inspirational ideas for architecture students and practitioners.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General INTRODUCTION

1

INTRODUCTION

Kinetic design and deployable structures have been used throughout history, but it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that there was an emergence of thought inspired by the speed and technological advances of the Industrial Revolution. Movements such as Italian Futurism and schools such as the Bauhaus in Germany formed a cradle of ideas including kinetic principles that were explored in art, industrial design and architecture. These early explorations looked to challenge the establishment and its static convention, introducing the fourth dimension of Time as a key element of the process of transformation (RA 2014).

In the 1950s the aerospace industry took an interest in deployable structures, and today probably dominates the research in this field. Deployable structures have found many uses in this industry. Large structures such as satellites, telescopes, solar arrays and antennas have to be packaged in much smaller volumes in spacecraft, and once in space they are deployed.

Transportation has also been a concern for earth-bound applications. Today there is also strong research being carried out on mobile and rapidly assembled structures, mostly made of lightweight deployable structures, for adaptable building layers and for mobile or temporary applications, such as emergency shelters for disaster relief or military operations.

As this is still an emerging field, there is no single agreed definition of a deployable structure. These structures are sometimes referred to as foldable, reconfigurable, unfurlable, auxetic, extendible or expandable structures; however, they are perhaps best understood from these descriptions:

Deployable structures are structures capable of large configuration changes in an autonomous way.

TIBERT, 2002, P1

Such structures may pass from a ‘folded’ to an ‘erect’ state; and in many cases the component parts are connected throughout topologically, but alter their geometry through the process of deployment. In the process of deployment the initial mobility is transformed into a final rigidity. But that is by no means the only possible scheme for structural deployment.

CALLADINE, 2001, P64

By the application of a force at one or more points, it [a deployable structure] transforms in a fluid and controlled manner. Despite such ease of transformation, these structures are stable, strong and durable.

HOBERMAN, 2004, P72

The following is the author’s own definition, which, it is believed, can be applied to any deployable type:

Deployable structures can expand and/or contract due to their geometrical, material and mechanical properties.

It would seem that deployable structures offer great potential for creating truly transforming, dynamic experiences and environments. Their lightness and transportability allow them to adapt to a society that is constantly evolving and changing. Furthermore, these are reusable structures that make efficient use of energy, resources, materials and space, thus embracing the concept of sustainability.

Today, not only engineers and architects, but origami scientists, biomimetic researchers, astrophysicists, mathematicians, biologists, artists and others are studying, designing and developing applications for an extraordinarily vast range of deployable structures. This includes mechanisms that have yet to be tested in architectural applications and are relatively unknown outside their scientific field. From these, the author has selected a variety of deployable structures (or principles) believed to have potential for technology transfer into architecture and design. This research also includes built projects and prototypes that are deployable or contain deployable elements.

This selection of deployables has been classified in typologies, classes and subclasses, shown in a tree diagram created and used as a navigational map, on pages 18–19.

This is novel design space.

DEPLOYABLE TYPOLOGIES

We are at an early, formative stage of its development, where we know and understand relatively little; where experiments are of the essence; where there are plenty of surprises in store; and where we have a long way before we reach that remote state where ‘principles’ can be enunciated and the whole business reduced to a branch of axiomatics.

CALLADINE, 2001, P64

This emerging field is rapidly changing and evolving in unpredictable ways. Research in this subject is carried out in disparate scientific fields, which do not necessarily always meet. But equally, many deployable inventions come from people who are not formally carrying out scientific research, such as artists. It is a field where applications spread across unforeseeable territories such as medicine, aerospace, art, industrial design, stage design, architecture, portable architecture, military equipment, infrastructure, vehicle components and fashion. Simultaneously, there are deployable structures for which no application has been found. Beyond pragmatic applications, deployable structures can also have philosophical implications (explored in Responsiveness, p146). The nature of this subject also seems to lie on the border of other research lines, such as robotics, biomimetics and material science. The scale of deployable mechanisms can range from a few millimetres (such as a deployable stent graft that can open a narrowed artery to treat oesophageal cancer; Kuribayashi, 2004) to vast structures that extend over thousands of metres (such as solar arrays deployed in space). Furthermore, this is a subject where ideas emerge that are difficult to articulate in words, and concepts can be best understood by acquiring experience with those deployable objects themselves, rather than entangling ideas in semantics and sophisms.

All these unattainably vast and incongruous parameters in which deployable structures operate seem to have made the task of giving an overall view of the subject a difficult one.

In 1973 Frei Otto classified typologies for deployable roof systems. Other classifications have been developed based on their one- or two-dimensional structural elements. There is also a classification by Ariel Hanaor for deployable structures capable of creating an enclosure, based on their morphology and their kinematic behaviour (De Temmerman et al, 2014).

The following is a holistic classification of a selection of deployables that offers an introduction to the subject and was carried out during my postgraduate studies in 2006 at the Oxford School of Architecture.

The principal issue that becomes apparent when attempting to classify deployable structures is that there are in fact two distinct approaches to developing a deployable. The first one is based on the structural components of the deployable mechanism: structures using this approach are classified under Structural Components. The second concentrates on movement and form inspired by various sources; these structures are described under the heading Generative Technique.

Two general types of Structural Components have been identified by experts in this field. These are Rigid Component Deployables and Deformable Component Deployables (You, 2006). These two main types have been used as a starting point for creating an assembly of typologies (including classes and subclasses) with potential for architecture and design. Other structural typologies cannot be classified within these two main existing types, thus other main types are created, Flexible Deployables and Combined Deployables.

Generative Technique includes deployable principles inspired by origami and paper pleat techniques, and systems inspired by biological phenomenology (a field known as biomimetics, i.e. morphology and motion in animals and plants). Generative Technique thus contains deployable studies which have originated through conceptual principles and can later be developed with numerous structural systems.

These deployables, which have until now remained as isolated pieces of research, have been placed in an architectural context by adding examples of built projects and prototypes that are deployable, or contain deployable elements, thus illustrating the potential of technology transfer of deployable concepts in architecture.

The tree diagram presented on the following page displays the selection and classification of over thirty deployables and it aims to highlight the diversity (not quantity) of deployable approaches and to introduce this emerging field to the reader.

It is impossible to approach the field of deployable structures with a single, general concept or theory.

MIURA AND PELLEGRINO, 1999

TREE DIAGRAM

.1-plgo-compressed.webp)

STRUCTURAL COMPONENTS

2

2.1 / STRUCTURAL COMPONENTS / RIGID

This type of deployable includes mechanisms made of rigid components. Their deployment process is fully controlled and the structure is stable at all stages of deployment.

Rigid-component deployables are considered to have great durability and have the most applications in architecture.

Deployables in this group are differentiated principally by the skin of their components. As a first general differentiation the skin can be made either of solid surfaces or latticework.

LATTICEWORK

These deployables have the minimum necessary structure to create the surface and the fold. The following latticework examples are differentiated by their mechanical geometry.

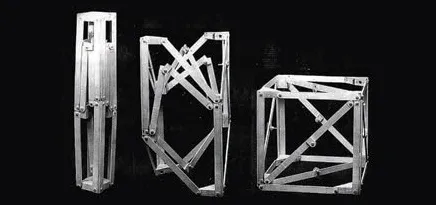

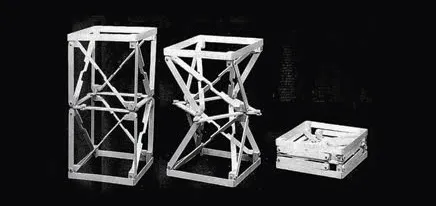

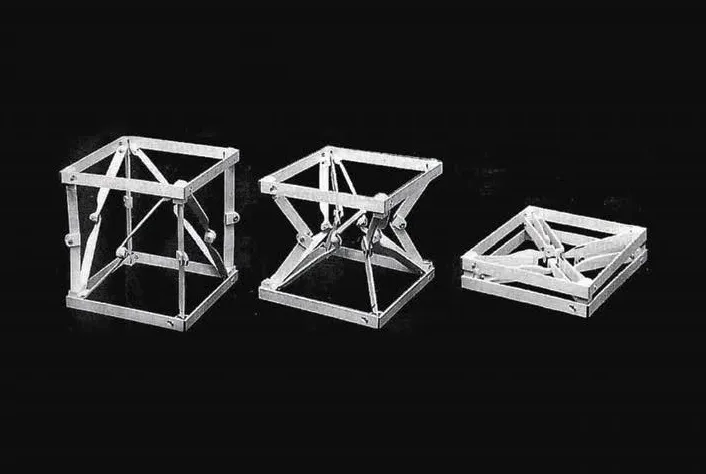

NASA Type Cubic

Alan L. Britt and Haresh Lalvani

This research project originates from the analysis of several deployable truss structures devised by Alan Britt for NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in the United States) in 1997 in the Morphology Studio of the Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture, New York, and in the studies done by Haresh Lalvani in the mid 1970s of topology and symmetry transformation.

Fig 1. Deployment sequence of NASA’s PACTRUSS geometry model.

Fig 2. Deployment sequence of NASA’s X-BEAM geometry model.

Fig 3. Deployment sequence of NASA’s STAC-BEAM geometry model.

The team aims to define a morphological design method that can generate deployable structures based on cryst...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Forewords

- Preface

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Structural Components

- 3.0 Generative Technique

- 4.0 Syntegration

- Sources

- Index

- Picture Credits & Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Deployable Structures by Esther Rivas Adrover,Esther Rivas-Adrover in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.