![]()

CHAPTER 1 Home

There is no way of isolating living experience from spatial experience. 1

The home, more than any other interior space, offers a clear indication of the constant and changing nature of patterns of social activity. Domestic space is a personal reflection of its inhabitants – a sign of their values and aspirations, a record of their character, culture and lifestyle. Therefore adapting a building in order to house its new inhabitants always places an emphasis upon the relationship and connections between both the lived experience of the space and its new occupation.

Domestic space often comprises a series of rooms that perform various domestic functions, such as cooking, eating, sleeping, relaxing and washing. The home will also enclose more esoteric entities such as memories, collections of objects and sentimental items – matter that has been solidified by the rituals of everyday life until it represents a person not only to themselves but also to other people. Therefore, when adapting a building to make a home, the composite of meanings, from the past, present and the future, form a complex weave of material and immaterial conditions. These are circumstances and situations that the designer can select and edit as required. As Doris Salcedo suggested in the above quotation, both spatial and living experiences are entwined to such an extent that there is no way of unpicking or separating them. The making of a home in an existing building always involves the amalgamation and manipulation of both lived and about-to-be-lived experiences.

The developed surface

The interior emerged in addition to constructional, ornamental and surface definitions of inside space that were architectural. The interior was articulated through decoration, the literal covering of the inside of an architectural ‘shell’ with the soft ‘stuff’ of furnishing. 2

The history of the home, created from reusing existing buildings, is a narrative that consists of the relationships between the past, present and future. The family house created by Sir John Soane between 1792 and 1823 epitomizes this narrative. Soane remodelled three adjoining London townhouses in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to create his family home. A striking feature of the interior of the house was the placement of objects that Soane had collected on his travels – a habit that from 1811 grew into an obsession, fuelled by the refusal of his sons to follow him into the profession of architecture.

What began as an understandable aspiration for an heir soured into an obsessive dream. 3

Traditional collectables such as prints and paintings were accumulated and displayed in the house, alongside objects as diverse as death masks, casts and even a tomb (the sarcophagus of King Seti of Egypt, which was placed in the basement). Each object was carefully positioned in the interior. The density of these clustered objects embodied the obsessive and compulsive nature of Soane, the fervent collector.

Looking east across the collection of objects in the dome area of the Soane Museum. A bust of Soane by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey is placed at the centre of the balustrade.

In Soane’s house the connection between the past, lived experience and the present was contained in this collection. The casts, statues and reliquary souvenirs that were attached to the walls and surfaces of the building formed a lining of the architectural envelope and created a skin that was independent of the existing shell and one that reflected the past back to the occupants. Soane’s house exemplifies the close connection between lived and spatial experience. It also embodies the notion of the domestic interior as essentially a surface condition, a lining of an existing building shell – a condition that is, as Charles Rice suggested above, one of the defining characteristics of the nature of interior space.

Modernism and the home

The beginning of the twentieth century was dominated by the reformative zeal of Modernism, which concerned itself, amongst other things, with the function of domestic space – culminating with the infamous claim by Le Corbusier that the house was a machine, and one that was to be lived in.4 The use of the machine analogy and the generally prevalent precise qualities of functionalism that it embodied eschewed any ambiguities in spatial form. Functionalism, a central principle of Modernism, was characterized by a rigid orthodoxy, one that was a decisive factor when designing and constructing a building. Its aphorism ‘form follows function’ suggested a rigid and inflexible bond between space and its use.

When buildings are adapted to accept new forms of occupation, determinant functionalist tendencies are considerably weakened. Although function might have initially shaped the building that is to be reused, its adaptation for a new use supersedes its original function. The old use can be considered redundant. Function is a flexible aspect of the design process in reuse. When the building envelope is adapted to contain a new form of occupation, new form does not follow the previous function. Instead new form will follow new occupation, possibly influenced by the old form of the building. The reuse of buildings is more correctly described through patterns or rituals of occupation. Therefore the determinant functionalist ideals of Modernism do not make sense when the function of a building changes through reoccupation and a new use.

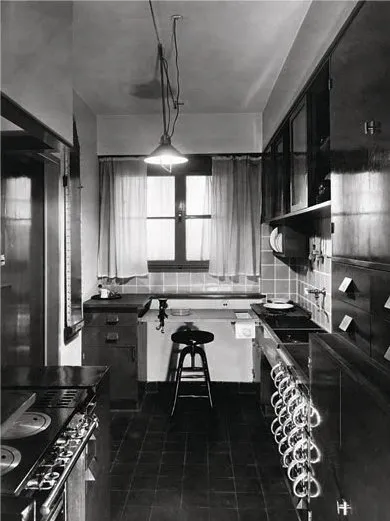

The Frankfurt Kitchen by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky.

The Pao for the Nomad Woman, an installation in a department store exploring new ways of living in the city.

House of the Future, an experimental home shown at the Ideal Home Exhibition of 1956 predicting what domestic space might be like in the 1980s.

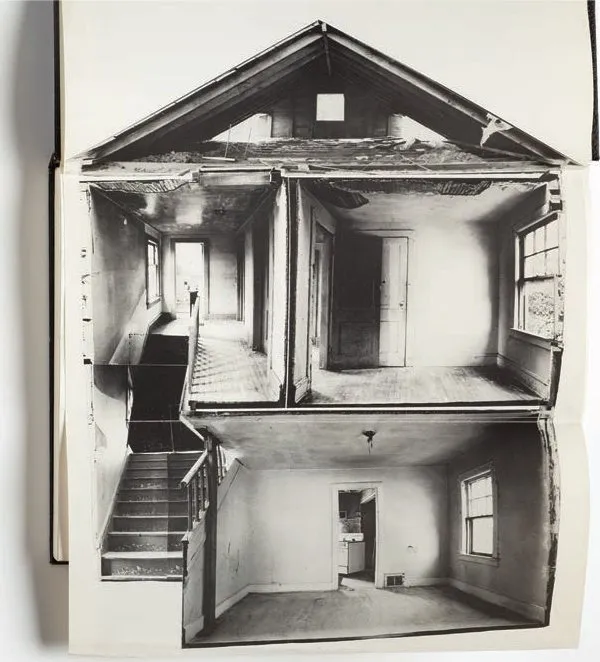

A ‘section’ of the split house designed by Gordon Matta-Clark in Englewood, New Jersey, USA. The image was constructed from a collage of photographs of the house interiors.

Zecc Architecten has transformed a former Catholic chapel in the Netherlands city of Utrecht into a spacious and light-filled home.

This is not to say that Modernism was not important in the history of reusing buildings. The machine aesthetic of Functionalism may find expression in the history of domestic interiors in the reuse of buildings through technological innovations. New developments of servicing technologies, such as heating and plumbing, lighting and structure, as well as research into new arrangements of space led to many new innovations and experiments in the home. The Frankfurt Kitchen was installed in 10,000 homes in post-World War I Germany in order to modernize its social housing programme. The first fitted kitchen, designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1926–7, radically changed domestic space, with a room for cooking and preparing food that contained built-in cupboards, integrated appliances and even a foldaway ironing board. All were precisely worked out in order to create an efficient and effortless space, one that drew inspiration from American social reformer Christine Frederick’s research into space efficiency.

Throughout the twentieth century the house was often used as a speculative device, a predictor of the future and a leitmotif of change. In the Daily Mail-sponsored Ideal Home Exhibition in London in 1956, the British designers Alison and Peter Smithson designed and constructed a one-bedroom house with a garden inside the main hall of the exhibition space. The futuristic house was set in 1980, was constructed from ply and clad in moulded plastic, with built-in appliances serviced by invisible plumbing and under-floor heating.

The Smithsons’ design imagined a future of endless raw materials yet their forward thinking included a silver foil roof to repel the rays of an overbearing sun and a direct link to a local nuclear power station, one that provided a constant source of energy to the house. Mobile furniture included a kitchen that could be moved to wherever it was needed and a bed that was sunk int...