![]()

Chapter One—The Gordys

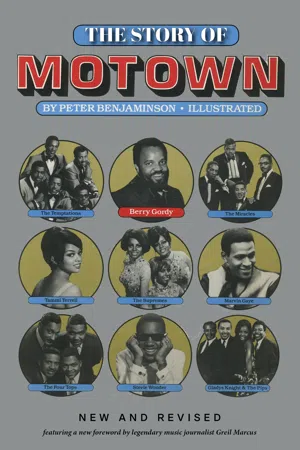

Berry Gordy Jr., who founded what became one of the most successful record companies in the country and the largest black-owned business in America, was born in 1929 on the lower west side of Detroit.

Appropriately for this songwriter turned businessman, whose company was accused of punching out hit tunes and performers the way the Ford Motown Company punches out auto parts, the house where Gordy was born was demolished later to make way for the Edsel Ford Freeway.

He was one of eight children, four boys and four girls: Robert, George, Berry Jr., and Fuller; Esther, Loucye, Anna, and Gwendolyn. The Gordy Srs. were married in 1918 in Milledgeville, Georgia, where Berry Sr. was a hand on a cotton farm. They moved north to Detroit in 1922 along with many other rural Southerners, black and white, attracted to the Motor City by the growth of the auto industry there.

But neither of the Gordy Srs. worked on the endless production lines in the vast gray auto factories slowly disfiguring a city that once advertised itself as America’s most beautiful. Neither was the kind to submit to factory discipline; both were intent on maintaining their economic independence.

Gordy Sr. inherited this desire for economic independence from his mother, who had been faced with a difficult situation on the death of her husband, the first Berry Gordy.

The family says the first Berry Gordy died when struck by lightning. That same day he’d had his first man-to-man talk about family affairs with his young son. The son, Gordy Sr., said he felt as if he’d grown from boy to man during that one eventful day.

Before he died, the first Berry Gordy acquired two parcels of land in Georgia. When he died, he owed more than $1,000 on them. In the turn-of-the-century South, when a black person died and left an estate, a white person was automatically appointed to administer the estate and granted a healthy fee for doing so. But the widowed Mrs. Gordy didn’t think it was right, just two or three days after her husband’s funeral, to hand over his land to some white person.

A friendly white neighbor told Mrs. Gordy that although it was the custom for a court to appoint a white person to administer the estate of a black person, no law required it. So, to the consternation of the local probate judge, Mrs. Gordy appeared in court, demanded the right to handle the estate herself, and was appointed administrator. Supporting herself and her children, she paid off the debt on the land and kept it in the family.

The first Mrs. Gordy’s determination to assert herself—and be economically independent—was passed down to her son and grandson. But her son, Gordy Sr., father of the record magnate, had his own flair for driving a hard bargain.

His bargaining ability showed to advantage in another incident involving the same Georgia land. By the late 1950s, the Gordy family holding in Georgia had grown to some 400 acres divided by a road. Kaolin, the mineral from which fine china is made, had been discovered nearby. For years, Gordy Sr. resisted offers of $100 plus mining royalties for the right to dig up the land in a search for kaolin and the right to purchase the land if sufficient kaolin was found.

Eventually, his brothers, who owned the land with him, insisted that some of it be parceled off to them so they could accept one of these offers. Gordy Sr. acceded to their wishes. A mining company paid the brothers $100 and was allowed to dig extensively. Kaolin was found, but not in marketable quantities. All the brothers got out of it was $100 and some dug-up earth.

But Gordy Sr. then got a $1,000 offer from the Anglo-American Clays Corporation for the right to dig on his portion of the land. Sniffing money, he bargained persistently and finally accepted an offer of $10,000 for the right to dig on the land and for a ninety-day option to purchase it for $140,000 if sufficient clay was found.

No more clay was found on Gordy’s land than had been found on his brothers’ and his land wasn’t purchased. But he had managed to obtain $10,000 for the same rights his brothers had sold for $100. He divided the money among those family members who had stuck with him in his earlier refusals to option off the land. The lesson in hard bargaining and family loyalty was not lost on the younger Gordy.

Gordy Sr. was no more intimidated by legal procedures or courtrooms than his mother had been. Nor did his ability to drive a hard bargain wither in an urban environment. In the late 1950s, the city of Detroit wanted to raze the neighborhood he was living in to make way for a hospital complex. The city offered him $20,000 for the building he owned, which included a grocery store, a print shop, and the flat above.

He refused. He and his wife were living in the flat, and, he told city officials, he’d just have to use the $20,000 to buy a place somewhere else. A few years later, when both Mr. and Mrs. Gordy Sr. were well-paid officials of Motown, Mrs. Gordy Sr. convinced her husband they could afford a house in a better neighborhood. Eventually, vandals made a mess of their old building, which they had left uninhabited.

Again, the city made an offer for the aging, sagging structure, but this time offered only $2,000 because the building had deteriorated. Gordy Sr. refused the offer, although his lawyers said he should accept it. He acted as his own lawyer before the condemnation jury, which rules on the fairness of purchase prices for properties in urban renewal areas.

When the city’s property appraiser took the stand, Gordy Sr. cross-examined him. “Didn’t you offer $20,000 for that building a few years ago?” Gordy Sr. asked. “Yes,” the expert replied. “Well, what would have done with it at that time?” Gordy Sr. asked. “We would have torn it down to build the medical center,” the witness said. Gordy Sr. replied, “So now it’s hardly standing. It’s easier to tear down. How can you say it’s worth less to you?” The jury agreed, and awarded Gordy Sr. the $20,000.

Gordy Sr. worked as a plastering contractor. His wife, Bertha, was a real estate and insurance executive and agent, and a political campaigner in her spare time. (She campaigned to elect G. Mennen “Soapy” Williams, later US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, as Governor of Michigan.) Together, the Gordys also ran a grocery store and a print shop.

With his light-colored skin, thinning white hair, white goatee, white suits, and Southern accent, Gordy Sr. bore a passing resemblance to Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame. Although the businesses owned by Gordy Sr. and his wife were hardly on the scale of Colonel Sanders’, to the Gordy children they may have seemed just as extensive. And they demanded hard work.

Helping their father in his plastering business was not the job of choice for the Gordy children. Plastering involved hard manual labor: hod carrying and cement mixing. Gordy Sr.’s extraordinary handshake was testimony to how hard he worked and how hard he expected others to work. Many men smiled strangely for a while after shaking hands with Gordy Sr.

The print shop and the grocery store were relatively popular, but Berry Jr. and his brother Robert didn’t like the print shop. They made up excuses to avoid working there after school.

A childhood friend of the Gordy family, Artie King, said the two brothers were so persistent in their attempts to avoid after-school labor in the family vineyards that to her they were “the two laziest guys in the world.” While living in California in the early 1960s, Mrs. King heard of Motown Records but couldn’t believe it was Gordy Jr.’s business, since he was always such a straggler. Since Gordy Jr. showed an appetite for hard work later in life, maybe his father’s businesses just didn’t appeal to him.

He couldn’t completely avoid working in the family enterprises, though, and learned a lot about the business world in the process. He later told an interviewer he learned how to be a businessman “through osmosis.” Some lessons were taught directly, however. The Gordy children learned to save a certain amount of money each week, for instance.

But another major lesson was taught by example: family unity. Whatever the Gordys did, they did together. Run the grocery store. Run the print shop. Bowl. Help the Gordy sisters when they took over the cigarette and candy concession at the Flame Show Bar. Cheer Gordy Jr. from the audience when he became a prizefighter, wherever he was fighting.

The Gordy’s neighborhood was a fairly nice place to live in. With eight children to support, Mr. and Mrs. Gordy Sr. didn’t have a great deal of money, but there was no lack of necessities for any of the children.

There were even some luxuries. In the basement below the Gordy businesses was a family recreation room, complete with piano. After an evening of skating, or dancing at the nearby Club Sudan, the Gordy children and their friends would sneak into the rec room to play records and dance. Gordy Jr. would amuse himself by picking out a tune on the piano. His nascent musical talent also surfaced when he won an honorable mention in a talent show for singing “Berry’s Boogie.” (He didn’t carry his musical interests very far until later, though. Boxing was more appealing to him at the time.)

Unlike what many white people like to think off as the typical black inner-city family, the Gordys were as middle class and upwardly mobile as they possibly could be. That Gordy Jr. grew up in such a striving, middle-class environment had a lot to do with why Motown was so successful. But for Gordy Jr., success was a long time coming.

![]()

Chapter Two—Gordy in the Ring

Perhaps it was only natural that teenage Berry Gordy was drawn into the amateur and then into the professional fight game. He lived near Black Bottom, the neighborhood that had spawned Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber. His older brother Robert and his younger brother Fuller were both boxers. And boxing was very popular in the Depression-ridden 1930s.

The Depression developed a lot of fighters; few people had the money to entertain themselves otherwise. Gym fees were very low, a boxer’s personal equipment was inexpensive, and a kid who wanted to box could get in condition even without a gym by running in the park and boxing in the backyard. (The US has far fewer licensed fighters now than it had in the 1930s.)

The Detroi...