Roots and Freedom

Human life needs a sense of belonging, firm roots, a sense of identity and of family. There is no lexicon of civility that does not recognize the importance of the border. Freud constructs psychoanalysis as a science of frontiers between the different mental realms (the unconscious, the pre-conscious, the conscious) and their different internal instances (Id, Ego, Super-Ego). Bion uses the language of psychoanalysis to emphasize the importance of the ‘contact barrier’ that separates the conscious from the unconscious, that which is internal from the external, the Me from the Not-Me. Without this border, life becomes undifferentiated, indistinct, and falls into chaos.1

Belonging to a culture, sharing a world, filiation, genealogy, race, descendance: the issue of identity and roots accompanies human life from the minute it arrives in the world. There is no human life without the memory of its roots. Life comes to life without protection, steeped in despondency, exposed to the chaos of the world, submerged by its vulnerability, but the child’s first scream acts as an appeal, an invocation, a cry for help from the Other. This is the fundamental sociality of existence. No one can save themselves. Without the Other, life falls into nothingness. However, in a way that might sound paradoxical, Freud imagines that the first task of life is also that of carving oneself out a protective nook in which to take refuge from the powerful and uncontrollable stimulations that come from within one’s own body and from the outside world. Human life at its earliest stages resembles that of a ‘bird’s egg with its food supply’, which must shelter that life still so defenceless and vulnerable.2 This is the primary urge of the drive: human life must defend itself from the world, which it experiences as a source of threat. Hence the insurmountable importance of a human institution such as the family. The life of a child demands to be inscribed in a symbolic process of filiation.

We should not dismiss the human drive to defend the confines of their individual and collective lives as an urge that is inherently barbaric or uncivilized. Freud himself tells us this, pointing out how life, both individual and collective, needs protection, reassurance, that it builds barriers in order to be able to bear the adversity of the world. Human beings have always protected their own existence, whether from the inhumane might of nature or the threats of enemies. The human urge to mark their own territory is an expression of the primarily securitarian nature of this drive. The art of marking out this border is a necessary operation for our survival. Life primordially searches out refuge from life and the definition of borders that are capable of circumscribing its own identity. The uprooting that characterizes life’s arrival in the world (no one chooses to be born, no one is master of their origins) is compensated for by an aspiration to become rooted in the place of the Other (be it the family, society, culture). Without roots or borders, both individual and collective subjects – the Ego and a population alike – would lack any sense of identity. It is no coincidence that, in clinical experience, it is the absence of boundaries that defines the schizophrenic life, a life that is radically lost, wandering, disintegrated, fragmented.

However, human existence is not comprised solely of a desire for belonging and reassurance, but also the urge to wander, a desire for freedom. While the desire for belonging includes individual life in a community (that of the family, for example), which offers it the right of citizenship, protection and security, that community cannot presume to encompass human life in its entirety. The desire to wander is the desire for freedom, the desire to travel, for adventure, to cross the border, and is equally important to human existence. It is no surprise, then, that the illness of an individual or a community is always somehow connected to the displacement of this relationship. While, on the one hand, an excess of belonging leads to a closing in on oneself, an erection of borders, conformism, uniformity and the exclusion of difference, on the other hand, excess wandering can lead to a severing of ties and loss of one’s own identity, disorientation, bewilderment, perhaps even culminating in the loss of oneself. These are the two ways in which the splintering of the ‘anthropological proportion’ can occur3 in the midst of the compelling need for the border, and the equally compelling need to move beyond it. When the sense of belonging prevails over that of freedom it creates an illness of life that, in the name of conformist adhesion to one’s own culture, waives freedom, sacrificing it to the needs of that life’s own security. In this case, everything that breaches the frontier, everything that lives beyond our own borders (be they individual or collective), is seen as a permanent source of threat. When, conversely, freedom and wandering overwhelm (being anthropologically disproportionate) belonging, when life is uprooted, all borders removed through the refusal of any bond or descendance, when life burns everything in the name of freedom that must be absolute, the symbolic bonds that provide us with the right to be citizens of the human community are ripped away.

The Uncivil Disease of the Wall

In his short story ‘The Great Wall of China’, Kafka offers a clear illustration of the pathology that can overwhelm the symbolic dimension of the border:

Against whom was the Great Wall of China to serve as a protection? Against the people of the north. Now, I come from the south-east of China. No northern people can menace us there. We read of them in the books of the ancients; the cruelties which they commit in accordance with their nature make us sigh beneath our peaceful trees. The faithful representations of the artist show us these faces of the damned, their gaping mouths, their jaws already furnished with great pointed teeth, their half-shut eyes that already seem to be seeking out the victim which their jaw will rend and devour. When our children are unruly we show these pictures, and at once they fly weeping into our arms. But nothing more than that do we know about these northerners. We have not seen them, and if we remain in our villages, we shall never see them, even if on their wild horses they should ride as hard as they can straight toward us – the land is too vast and would not let them reach us, they would end their course in the empty air.4

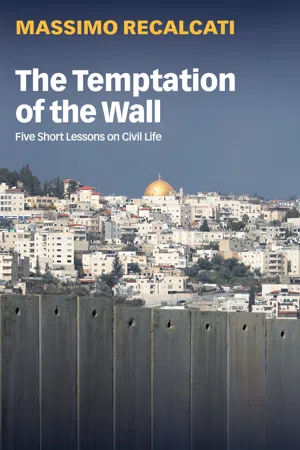

The stranger lives beyond the border – ‘the people of the north’. As foreigners, they are an insidious threat against which we must strengthen our borders. The infinite extension of the wall, as described by Kafka, must be capable of exorcizing this threat through the creation of an unbreachable boundary. The stranger is seen as a malign and cruel entity, capable of violating the very intimacy of our own families. This is the basic principle for every one of any identity’s paranoid pathological developments: every foreigner carries the risk of a nefarious contamination of our own identity. The alterity of those who live beyond the border is a danger that must be thwarted, defended against. And so, the border becomes sclerotic, shell-like, it is transformed into fences, barbed wire, walls that block everything that lies on the other side.

This pathological metamorphosis of the border forgets to consider how the symbolic function of the border is not just that of marking out our own identity (collective or individual), but also that of guaranteeing exchange, transition, communication with the stranger. This is why the great psychoanalyst Bion recognized porosity as one of the fundamental attributes of the border. In the rush to build up fence posts, walls, barriers, organized defences we see today, in this time seemingly dominated by an unbridled urge for security, the border risks becoming a wall that makes any exchange impossible.5 This closure ends up prevailing over openness. That sense of belonging loses all contact with wandering and freedom. The border loses its porosity. Here, we rediscover two of the greatest forms of incivility that subvert any lexicon of civility. On the one hand is the pathology connected to the dissolution of the border, its absence, its symbolic non-inscription. This is the pathology that finds its paradigm in schizophrenia: indistinction, confusion, chaos, a lack of differentiation. It is the unilateral prevalence of uprooting over being rooted, of wandering over belonging. On the other, however, is the pathology of the border, which involves its transformation into a wall, a fortress, a stronghold. In this case, identity is paranoically hardened against any difference. The foreigner becomes a threat, a horror, the terrifying enemy we saw in Kafka’s description.