![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Atypical Bodies

The Cultural Work of the Nineteenth-century Freak Show

NADJA DURBACH

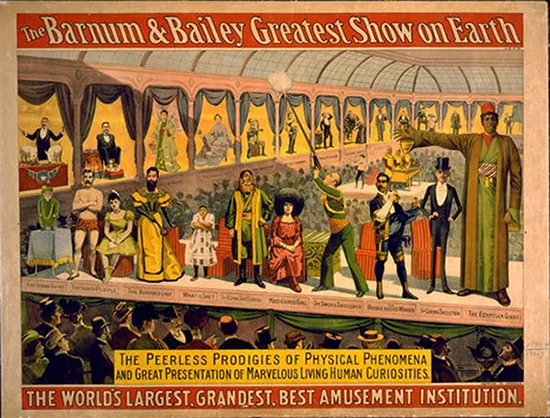

On January 6, 1899, performers with the Barnum and Bailey show (Figure 1.1), which was appearing in London, held an “indignation meeting” to protest the use of the term “freak” as applied to the “human abnormalities and specialty artistes” on display. They resolved that merely because they were “fortunately, or otherwise” possessed of “more or less limbs, more or less hair, more or less bodies, more or less physical or mental attributes than other people,” and as such differed from “the ordinary or regulation human being,” there was no reason that they should be called “freaks.” This term had been widely used throughout the nineteenth century to refer to those who displayed their atypical bodies for profit, but these performers maintained that it was “opprobrious” and “without any specific meaning in an anatomical sense.” They further argued that their physical distinctions might in fact be assets and intimated that “some of us are really the development of a higher type, and are superior persons, inasmuch as some of us are gifted with extraordinary attributes not apparent in ordinary beings.” Their resolution underscored that although they had been “created differently from the human family as the latter exist to-day,” these bodily variations might have been expressly “for their benefit,” intimating that in the future all persons might be blessed with nonstandard forms (“Freaks in Council” 1899: 19). This meeting was most likely a publicity stunt. Newspaper coverage of the event used it primarily to highlight the acts that would be on display at the show, which included a bearded lady, armless and legless performers, a giant and a dwarf, a man with a parasitic conjoined twin, an elastic-skinned man, and the so-called Wild Men of Borneo. But whether it was an authentic expression of discontent over appropriate terminology, as some scholars have argued (Chemers 2008: 97–101), or an instance of the humbug inherent in all of Barnum’s promotional materials (Lentz 1977; Cook 2001), what historians have called the “revolt of the freaks” sheds light on the complexities of the freak show, the primary cultural site for public and professional encounters with atypical bodies in the nineteenth century.

FIGURE 1.1 The Barnum and Bailey Greatest Show on Earth.

This chapter focuses on the cultural work that the freak show performed in the long nineteenth century. This is because if we wish to find where atypical bodies were most visible to the public, then we must look to their commercial display. By exposing these bodies for all to see, rather than segregating and silencing them through the practices of institutionalization, freak shows demanded that society engage with the fact of corporeal variation. Throughout the nineteenth century, human oddities from around the world crisscrossed the oceans, appearing in North American and Western European cities, towns, and rural communities. Some continued on to Eastern Europe and into the Middle East, tracing and retracing what soon became an established freak show route. By the middle of the century, the freak show had thus become firmly embedded within an increasingly cosmopolitan entertainment industry. In fact, these exhibitions were one of few nineteenth-century leisure activities that attracted an extremely broad audience, which transcended national borders and cut across lines of class, gender, and age. Curious members of both the public and the medical and scientific professions eagerly flocked to see bodies that defied the norms of corporeality and challenged the divide between human and animal, male and female, black and white, civilized and savage, slave and free, self and other, as well as a range of other binaries that increasingly structured modern Western societies.

This chapter argues that it is to the popular and professional debates these spectacles generated over how to interpret extraordinary bodies that we must turn if we are to understand the various ways that the nineteenth century framed the atypical body. Section 1.1 seeks to complicate how we use the term “disability” when writing about atypical bodies in the past. It suggests that rather than seeing freak performers as people with disabilities, it is more historically accurate to locate them in relation to a range of attitudes toward and anxieties about the body that were relevant in the nineteenth century. These discourses deliberately resisted essentializing the meanings of physical difference and kept the ambiguous nature of these bodies alive. Section 1.2 explores the issue of agency, challenging the widespread assumption that freak shows were merely voyeuristic and exploitative. Instead, it demonstrates that the relationship between performers and spectators was more interactive and complex than we might imagine and that freak shows often provided financial stability and thus independence to those who were economically vulnerable. In the case of ethnographic acts, however, this issue was more complex, as the racial systems of colonialism and slavery further limited these performers’ range of life choices. Section 1.3 seeks to locate these ethnographic shows within the wider history of the display of atypical bodies, arguing that these exhibitions were crucial sites for the scientific study of “the races of mankind.” By displaying non-Western peoples alongside bearded ladies and legless men, these shows produced racial and ethnic difference in dynamic relationship to other forms of corporeal “deviance.” This section then moves to a discussion of scientific medicine’s use of the freak show for its raw material. It posits that the medicalization of the anomalous body emerged in the nineteenth century not in contrast to freakery, but directly out of negotiations between scientific professionals and freak performers. This chapter suggests, therefore, that the freak show should not be dismissed as merely prurient, exploitative, and thus degrading to those who inhabited nonstandard bodies. Rather, it was a critical site for negotiations around the meanings attached to physical diversity and thus central to understanding the place of the atypical body within nineteenth-century culture.

1.1. HISTORICIZING THE ATYPICAL BODY: ATTITUDES, ABILITY, ABNORMALITY, ANXIETY, AND AMBIGUITY

The language deployed by the performers involved in the “revolt of the freaks” resisted a reading of their atypical bodies as inherently less able. Although they acknowledged that they had been “created differently,” those who attended this purported meeting suggested that their physical peculiarities could be interpreted “as additional charms of person or aids to movement” rather than in terms of disability, a term in limited circulation at this time (“Freaks in Council” 1899). During the nineteenth century, there was no omnibus term for those with atypical bodies, no category to which all, regardless of the specificity of their physical differences, could belong. Instead, a variety of labels, including “the defective,” “the deformed,” “the infirm,” “the impotent,” or “the crippled,” were deployed to categorize particular forms of impairment in specific contexts (Stone 1984: 55). The use of these different terms distinguished bodily variations from each other; more significantly, it signaled appropriate social attitudes and cultural responses to these bodily states that included identifying those deserving of financial assistance. Charles Dickens’s Tiny Tim, for example, is an archetypal “crippled” child, meant to evoke pity, empathy, and thus charity in the reader. This had particular resonance at Christmas, “a kind, forgiving, charitable time,” A Christmas Carol articulates, “when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys” ([1843] 2003: 42). Dickens’ Silas Wegg, however, the one-legged blackmailer in Our Mutual Friend, while similarly impaired, is never constructed as a “fellow passenger.” Dickens does not describe the wooden-legged Wegg as a “cripple” precisely because, as a villainous character, Wegg was meant, as Martha Stoddard Holmes has argued, to elicit “righteous outrage” in readers, not pity (2004: 94–132). Wegg’s impairment thus signals that he, unlike Tiny Tim, has in fact been consigned to that race of creatures bound on other journeys.

The term “disabled” did circulate in the Victorian period and was sometimes used to signal bodily states wrought by illness, injury, or old age. But it was rarely used at this time to describe those born with congenital anomalies. Instead, “the disabled” emerged as a category primarily in relation to wounded soldiers and sailors, particularly the limbless, who, having sacrificed their bodily integrity for the safety of the nation, had the right to make demands upon the state.1 The American Civil War began to shape this new body–state relationship, and the concomitant rights that accrued from it, in the second half of the nineteenth century. For Europeans and their colonial subjects, it was not until the First World War that this particular meaning of “disability” took root. “Disability” thus evokes an understanding of bodily difference that expresses a specific relationship among the self, the state, and society that was largely shaped by the experience of modern mass warfare’s impact on the body. The problem with using “disability” to interrogate the nineteenth-century freak show, then, is that scholars have often collapsed the project of analyzing the ways in which societies have dealt with atypical bodies over time and space and the specific meanings and connotations of this word. In an otherwise theoretically rich study of the American freak show, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson has argued that the “wondrous monsters of antiquity, who became the fascinating freaks of the nineteenth century, transformed into the disabled people of the later twentieth century” (1997: 58). This suggests that these terms and the meanings attached to them were interchangeable or evolutionary understandings of physical difference.

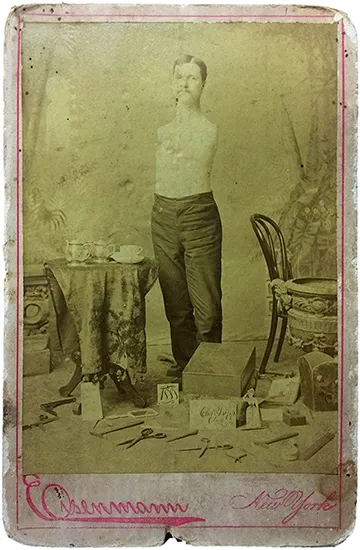

I deliberately employ the term “freak” when discussing those who displayed their atypical bodies for profit because it was the most common term in use for these performers throughout the nineteenth century. But using it also highlights that the practice of enfreakment was a culturally and historically specific approach to manufacturing and managing the divide between the “normal” and the “abnormal” body. In fact, freaks did not necessarily think of themselves as physically less able than those with standard bodies. As the resolutions that emerged from the “revolt of the freaks” suggested, freak performers often had bodily anomalies—abundant hair, unusual pigmentation, extra appendages—that in no way interfered with their cognitive or physical abilities. Those whose physical differences were assumed to be compromising invariably incorporated into their acts demonstrations of their capacities. Eli Bowen, a “legless wonder,” could perform a wide range of skilled acrobatic tricks; his promotional materials underscored that he moved “swiftly and gracefully” and that all of his movements were “dexterous” (Bogdan 1988: 215). Oguri Kiba, who participated in the “revolt of the freaks,” was armless. Her publicity materials nevertheless stressed that this did not interfere with her ability to undertake skilled labor, explaining that, “with her highly educated feet she does more things and does them better than most people fully endowed by nature with hands.” Using only her toes, “she sews, threading even the finest cambric needles, spins, uses hammer, saw, and plane, makes toy ships, builds water-tight tubs and firkins, cuts delicately traced lace out of paper, makes artificial flowers, and shoots with bow and arrow with wonderful accuracy” (Dean 1899: 8–9). The armless Charles Tripp sold a souvenir photograph that depicted himself surrounded by the tools he could skillfully manipulate with his feet (Figure 1.2). Freaks of all varieties thus tended to construct themselves as skilled and adaptable. That performing in the freak show allowed them to lead independent lives further underscored their able-bodied status. For if the term “disability” was rarely used in the nineteenth century to refer to those with nonstandard bodies, the term “able-bodied” was a crucial cultural reference point. In the United Kingdom, those who could work and were able to support themselves financially without relying on the state or charity were by definition able-bodied. The fact that they were being paid to exhibit their bodies and could earn their own keep thus allowed freak performers to identify not as disabled, but rather as able-bodied.

FIGURE 1.2 Charles B. Tripp, Photograph by Charles Eisenmann, c. 1890.

Freaks often stressed, therefore, that despite their unusual forms, when not onstage they led rather unremarkable, and in fact typical, lives. An 1898 article entitled “‘EVEN AS YOU AND I’ At Home with the Barnum Freaks” argued that “in public they are ‘freaks,’” but when they were “off their platforms and their pedestals it is pleasant to find that, with the one particular reservation in each case, they are just men and women, normal and healthy, ‘even as you and I’” (Goddard 1898). Although those who participated in the “revolt of the freaks” themselves celebrated their distance from the “regulation human being,” they likely would have welcomed this kind of publicity that situated them as healthy members of the human family when not explicitly performing their otherness. Miss Annie Jones, the bearded lady who purportedly instigated the “revolt of the freaks,” “would never be taken for a ‘freak’” when not onstage, her promotional material stressed, “as she dresses in fine taste, and conceals her features by a cunning combination of black silk handkerchief and deep veil” (Dean 1899: 12). When Tom Norman exhibited Joseph Merrick as “the Elephant Man” in 1884, he similarly stressed in Shakespearean fashion that “were you to cut or prick Joseph he would bleed, and that bleed or blood would be red, the same as yours or mine,” explicitly drawing a commonality between Merrick’s body and those of his spectators (Norman and Norman 1985: 104).

But freak shows also obviously depended on drawing a distinction between the “normal” bodies of spectators and the “abnormal” bodies on display. They attracted audiences not only by using atypical bodies as others against which the self could be measured, but also by stimulating curiosity about the instability of race, gender, sexuality, class, civilization, colonialism, immigration, slavery, individualism, and, in fact, the very boundaries of humanity. “Spotted boys,” whose skin was neither black nor white, challenged racial typing and, by extension, the existence of race-based slavery; conjoined twins raised troubling questions about individuality and the nature of the self; extremely hairy persons complicated the divide between human and animal, contesting the theory and nature of evolutionary processes. Freaks thus attempted to draw the spectator’s eye to certain aspects of their bodies and performed roles that were intended to structure how their specific corporeal anomalies should be read.

This is why those who performed as freaks often enhanced their acts by adopting what Robert Bogdan has identified as aggrandized or exoticized modes of presentation (1988: 94–116), or by promoting themselves as liminal beings. It was the “techniques of exhibition in which corporeal difference is literally staged,” including costumes, choreography, and supporting materials such as souvenir photographs and pamphlets, which in the end constructed the anomalous body as freakish (Stephens 2005: 7). For as Garland-Thomson has argued, the freak was “fabricated from the raw material of bodily variations” for entirely social purposes; the “freak of nature,” she insists, was always in fact a “freak of culture” (1996: xviii, 7). The “freak” was both an occupation—like “actor,” “dancer,” or “acrobat”—and a role that was produced in collaboration with the audience whose spectatorship itself shaped the construction of the performer’s body as aberrant (Stephens 2006: 487). Freaks thus always attempted to have it both ways: they profited off their bodies’ otherness by using them to generate a range of titillating anxieties while at the same time asserting that they were not only “normal” but “able-bodied.”

The freak show thus traded in ambiguity. If it directed the eye to see certain bodily traits, it nevertheless sought “to expand the possibilities of interpretation” of the atypical body, rather than containing its definition “through classification and mastery” (Garland-Thomson 1999: 95). These spectacles perpetuated the multiple potential meanings attached to corporeal anomalies, a discourse that had clear cultural reverberations. In his 1841 novel The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens featured two diminutive people: “Little” Nell and Daniel Quilp. In realizing these characters, Dickens borrowed heavily from the freak show’s exhibition of a range of “miniature” peoples. But, despite their shared physical resemblance to sideshow “midgets” and “dwarves,” Nell and Quilp were not intended to elicit identical affective responses in readers. Nell’s “small and delicate frame” was part of Dickens’ positioning of her as a suffering, self-sacrificing, and ergo sentimental character who serves as the novel’s heroine and thus emotional core. Quilp, in contrast, who was “so low in stature as to be quite a dwarf,” is figured as grotesque, ugly, and lecherous because he was meant to be read as a melodramatic villain (Craton 2009: 41–85). That Dickens used remarkable smallness within the same text to elicit diametrically opposed reader responses to his characters suggests that what he imbibed from the freak show and then widely perpetuated was a refusal to essentialize the atypical body. Rather than trafficking in the degradation of difference—a facile and narrow understanding of freakery—throughout the nineteenth century these exhibitions succeeded in keeping the wondrous nature of corporeal variation alive by cultivating ambiguity and thus allowing for myriad interpretations of the possible meanings of physical difference.

1.2. AGENCY AND THE ATYPICAL BODY

The revolt of the freaks encouraged potential spectators to reject the idea that these human curiosities found the commercial display of their wondrous bodies shameful, as they disparaged only the negative connotations of the language of freakery, imposed on them “without our consent,” but not their exhibition itself (“Freaks in Council” 1899). This raises critical questions about the agency of freak show performers. Some scholars have rightly problematized the meaning of choice and consent in the case of individuals who inhabited anomalous bodies, arguing that the freak show was an inherently exploitative institution (Gerber 1990, 1996; Mitchell and Snyder 2005). This reading, however, diminishes the agency of performers and ignores the realities of the nineteenth-century economy and the lack of social services available to those born with bodily anomalies, both of which may have limited their ability to support themselves in other ways. Although it would be misleading to celebrate the freak show as the only real sanctuary for those with atypical bodies, it is equally historically inaccurate to position nineteenth-century freakery as always already an unscrupulo...