![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Atypical Bodies

Queer-feminist and Buddhist Perspectives

BEE SCHERER

1.1. INTRODUCTION: A MULTIVERSE OF ATYPICAL BODIES

Atypical bodies in the Modern Age, as constructed through, for example, gender binarism, ableism, and “sanism” (Birnbaum 1960), are deeply interpolated in Global Northern hegemonic discourses of scientific positivism and capitalism. The cultural discourses and projects of modernity construct corporeal typicality within frameworks of medico-psycho-social normativities, replacing the systemic violence of religio-cultural value judgments as inscribed on individual bodies with equally violent “scientific” societal scripts of centers and margins of corporeality and embodiment. Challenging these re-delineated structures of corporeal normativity, postmodern modes of cultural critique have been increasingly deconstructing, queering, “cripping,” and “madding” the oppression of—in (late-/neo-/post-) Marxists terms—the medico-psychiatric industrial complex, which, in aid of neoliberal (late) capitalist exploitation, propagates the manageable uni/con-formity-in-isolation of human “production/consumer units” alienated from both their uniqueness and their mutual interconnection. Queer and queering (and, analogously, crip and cripping; McRuer 2006) are terms that point to “critical impulses” (Kemp 2009: 22) empowering embodied subjects to inhabit the very “open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning” (Sedgwick 2004: 8) beyond identitarian reductionism and essentialism.

This chapter explores how atypical bodies and body performativity—in the terms of contemporary queer theory, starting with Butler 1990—(can) disrupt the (late) modern nexus of socio-corporeal oppressions. Among the possible venues to showcase the disruption that any contestation of socio-corporeal scripts entails, bodily alterity could have been explored in relation to, for example, twentieth-century fascist eugenics, neurotypical normativities, and the surviving psychiatry & reclaiming madness movements (psychiatric survivor, Mad Studies, etc.). Corporeal othering can be demonstrated through beauty ideals and notions of ugliness and deformation (including fatism, female muscularity and hairiness, and ageism) as inscribed onto the collective psyche by pluto-/medio-cratic capitalist machineries such as mass media and advertising, fueled by and aiding hetero-cis patriarchy. Or one could examine in more detail binary-gendered and religious-cultural body scripts and violence, such as infantile genital cuttings and intersex surgery. The identity performances of consensual/voluntary body modification, tattooing, and body cyber-enhancements could also have been explored, just as could questions of speciesism, non-human rights, and trans-/post-human ethics.

Another possible wide-angle avenue would follow the complex intersections produced by ever-pervasive transnational centers of embodied power, which includes, but is not limited to, male, heterosexual, cisgender (identifying with the sex assigned at birth), procreative/premenopausal, white, possessing a citizen/immigration status privilege, Global Northern, unimpaired/“abled,” body-normative, affluent, middle-to-upper class, professional, and secular-Christian.

Beyond ableism, the atypical body in the Modern Age includes most prominently the female body and the queer (including trans*, nonbinary, and intersex) body, but also the religio-culturally othered body (e.g. the Islamic veiled body), the orientalized and colonized body, and the non-human body. In this chapter, I sketch parts of this wider-angle approach while also following intersecting showcase avenues, informed and limited by my own Global Northern white queer Buddhist positionality. In this way, I offer intersectional (queer-/crip-/trans-) feminist cultural-philosophical views on atypical bodies in the Modern Age, infused by Buddhist “theology” (or Buddhist critical-constructive reflection).

1.1.1 Othering and variability

Key to the notion of “normalcy” or “typicality” is Othering: the strategic process in psychological (Lacan) and social discourse (Derrida) of identifying an “Other” as excluded from both the notion of a “Self” and from the construction of a stable group identity in relation to power and value productions. The feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir identifies alterity (altérité) as a foundational principle of consciousness, translating from individual to social identity formation (de Beauvoir [1949] 2010: 26–7). Emmanuel Levinas talked about an otherness that, through the “imperialism of the same,” preserves or even reinforces normativities (see Isherwood and Harris 2014: 2). Michel Foucault describes the creation of altérité in relation to folie (madness) as follows:

The history of madness would be the history of the Other—of that which for a given culture is at once interior and foreign, therefore to be excluded (so as to exorcize the interior danger) but by being shut away (in order to reduce its otherness); whereas the history of the order imposed on things would be the history of the Same—of that which, for a given culture, is both dispersed and related, therefore to be distinguished by kinds and to be collected together into identities. (Foucault [1966] 2005: xxvi)

Foucault’s observations are particularly pertinent in the context of the nascent movement of victims of sanism and survivors of the medico-psychiatric industrial complex who are reclaiming madness in Mad Studies and Mad advocacy (e.g. Cole et al. 2013; Mills 2013; Burstow et al. 2014; Spandler et al. 2015). Abstracting from this particular facet, Lacanian, Derridean, and Foucauldian approaches to alterity are productive when examining (post)modern “atypical bodies,” as they can help us to understand the underlying phobias and power interests that drive the creation of centers that always must produce margins, stigmatization, and deviance in order to be effective in their own self-serving discourses. For our purposes, we need to point to the emergence of Critical Disability Studies broadly conceived (see the excellent introduction by Goodly 2017), which challenges the systemic othering of atypical bodies (and minds) implied in the capitalist individualization-cum-alienation of impairment and medical conditions. Such challenges take form through Social Model approaches to “disability” as propagated by key thinkers such as Colin Barnes, Mike Oliver, and Vic Finkelstein (see Goodley 2013: 633); some take poststructuralist (see Corker and Shakespeare 2002: 3), “crip theory” (McRuer 2006), “dismodernist” (Davis 1995a), and “critical realist” approaches (Siebers 2008; Shakespeare 2017) or a “study in ableism” approach (Campbell 2009). Hence:

Critical disability studies start with disability but never end with it: disability is the space from which to think through a host of political, theoretical and practical issues that are relevant to all. (Goodley 2013: 632)

Relatively unnoticed by the Critical Disability Studies field that thus emerged during the last three decades, the eighteenth-century cultural scholar and queer-cum-impaired activist Chris Mounsey argues for the need to move our attention away from disembodied/disembodying theory to the focus on concrete embodiment, both paradigmatic and yet unique: Mounsey calls to replace “disability” with a new sign(ifier) “variability”: same, only different (2014). If we theorize this “variability” further, we can claim that, as a linguistic symbol, it promises to speak to Derridean notions of the impossibility of the absolute Other. Different, here, is not in the sense of Levinas and de Beauvoir reinforcing Self and Same and the norm(ativitie)s they produce. Same, only different is subversive of hierarchies, just as in Homi Bhabha’s famous notion of “the ambivalence of mimicry (almost the same, but not quite)” (Bhabha [1994] 2012: 123): through variability, all embodiments are taken serious in their nonhierarchical autonomy and non-hegemonized equivalence (see Scherer 2016a). “Atypical bodies” can become variable bodies, counteracting both essentialized alterity and systemic erasure of individual embodiment.

The following will focus on variable bodies as actively dis-abled, impaired, and oppressed through the notions of atypicality, normativity, and normalcy in the example of gender/sexuality-related embodiments. Feminist Disability Studies (Garland-Thomson 1997, 2004) and (transhuman) Cyborg Theory (Haraway 1991; see Kafer 2013: ch. 5, 103–28) advance our understanding of corporeal atypicality in its “fleshy” relationality. The queer-/trans-feminist perspective offered in the following sections (1.2 and 1.3) is naturally intersectional, and the focus on gender/sexuality is merely one of several possible routes as identified above, including class and socioeconomic power, as well as race, heritage, and ethnicity. The discussion is widened in section 1.4 by focusing on religious/cultural intersectionalities and tensions. In the final section (1.5), Buddhist philosophical perspectives infuse the discussion in order to propose new avenues to notions of corporeal atypicality.

1.2. DANGEROUS MARGINS: FEMALE BODIES VS. PATRIARCHAL TYPICALITY

The largest marginalized group of atypical bodies recognized in evolving and often reluctant manners during the “Modern Age” (as the time period this volume explicitly focuses on) is female bodies. Beyond “disability” and sexuality (Shildrick 2009), the Othered gendered body is the dangerous margin to patriarchal typicality. As de Beauvoir (1949) argues, femininity is alterity and inferiority; the social Self is man, woman is the Other. The female body is the atypical, alter body par excellence, which—if we follow Levinas’ view on alterity—stabilizes, solidifies, and reinforces the fragile, labile, and elusive Self (male): “Femininity inhabits masculinity, inhabits it as otherness, as its own disruption” (Felman 1993: 65, emphasis in original).

Within most premodern systems of governmentality, women’s atypicality, otherness, and inferiority were predominantly conceptualized in (socio-)religious terms. When discourses of modernity by and large started to supplant religious discourses and governmentalities with “scientific” (e.g. medical) ones, the equation of the female with alterity became shrouded in seemingly “objective” discourses around female embodiment and the ensuing mainstream medical pathologization of female bodies in the nineteenth century. In fact, this discursive disabling of women (e.g. in the form of the construction of menstrual insanity and hysteria) begins much earlier than the late nineteenth century (e.g. see Kassell 2013 for the Modern Age; see also Cook 2004; Hall 2012). What is new during the Modern Age, with the onset of social liberation movements and feminism, is the full emergence to social consciousness how the sociocultural construction of the female body as atypical and deficient has been utilized in aid of a wider system of oppression. Through the different waves of feminisms (three to four, and counting) in the Global North over the period of the last 120 years, the marginalized atypical bodies demanded equality, agency, and self-determination. In the second half of the twentieth century, second-wave feminism in the Global North set out to dismantle all-pervading patriarchy, in particular the patriarchal oppression of women and the social construction of women (de Beauvoir’s famous aphorism from 1949 on ne naît pas femme: on le deviant—“a woman is not born but made”) in aid of male hegemony. Following on from this, third-wave feminisms broadened emancipatory impulses: liberation from oppression included the deconstruction of gender (from Women’s Studies to Gender Studies and Queer Studies to Intersectional Social Justice). Hence, third-wave feminism pays closer attention to different areas of privilege, such as socioeconomic power and whiteness. (Fourth-wave feminism is a recent, somewhat contestable periodization for shifting foci in the 2010s toward persisting sexist violence; arguably, fourth-wave feminism is reprising some fundamental second-wave themes for the twenty-first century). All of these feminist, “dangerous” voices from the seemingly ever-decreasing margins have been—and are—threatening the patriarchal disabling of one half of humanity by the other.

1.3. TRANS/QUEER BODIES AND APHALLOPHOBIA

However, during the post-second-wave process of widening and complicating the emancipatory struggle, a rift appeared around the intersectional widening of the counter-patriarchal fight to include “queer bodies.” While rifts in feminist stances in the 1980s centered around sex-positive versus anti-pornography feminists, from the 1990s onward, the most pronounced fissures in feminist communities of practice focused on “the loss of the woman” in feminism. Some self-proclaimed “radical feminists” announced their discomfort with Gender Studies, transgender liberation, and intersectional solidarity, identifying these themes as either distractions or, worse, as harmful “Trojan horses” of patriarchy. Indeed, the fight against patriarchy, they claimed and still claim, has been forgotten in third-wave (and, less so, fourth-wave) feminism.

Yet, in the fight against (hetero/cis-)patriarchy, contemporary queer-feminist resistance, solidarity, and ethics arguably necessarily address sexual and gender identity justice intersectionally in their complex interpellation with the messy wealth of identitarian markers and constructs inscribed onto individual bodies by, among other, reproductive-patriarchal, (neo)colonial, racist, nationalist, classist, ageist, ableist, and other socio-corporeal normative discourses. In contrast, some second-wave “radical feminists” need to answer the question of whether their retention of the binary construction of gender in criticism of queer theory and their trans-exclusivity in opposition to trans-solidarity, as well as their lack of reflection on their Global Northern/white privilege, are not constituting the real Trojan horse in the fight against sexism and patriarchy.

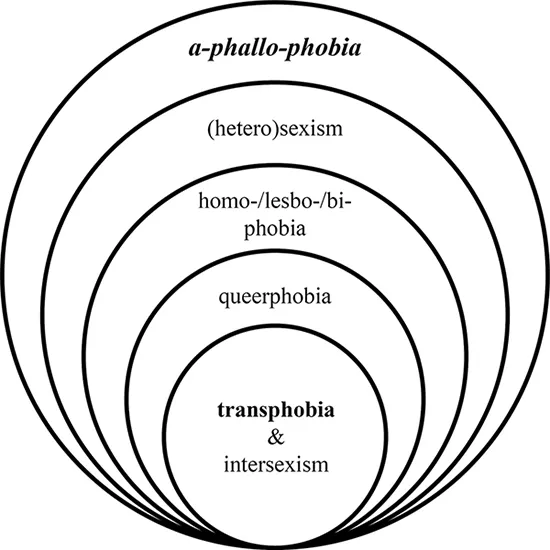

The meta-analysis of recent trans* mental health surveys in the Global North demonstrates an unrivaled and depressingly high prevalence of mental distress, suicidal ideation, experience of harassment, and violence among trans* people due to transphobia (Scherer 2014). I maintain that trans* mental health statistics show the clear symptomatic for the underlying wider system of oppression that so intimately links groups marginalized by patriarchal bio-politics. In the following, I argue that the misogynic-patriarchal “atypicality” construction of the female body is, in fact, the widest expression of a social phobia in aid of this oppression. I maintain that sexism and phobia of queer bodies (homo-, lesbo-, bi-, queer-, trans-, and intersex-phobia) form an inseparable nexus of bio-political oppression around the core mechanisms of patriarchy. I have termed this phobic matrix, with a half-ironic nod to Lacan, aphallophobia: the fear of the instability of gender binary power privileges or the fear of losing (straight, cis) male hegemony (phallus) as the systemic power broker of hetero/cis-patriarchy (Scherer 2014). To put it simply, patriarchy works in two steps: (1) reducing the human gender lexicon into binaries—male and female; and (2) claiming the superiority of one (male). Hence, any feminism that only opposes Step (2) is intrinsically weakened from the outset and adds credibility to the more fundamental premise of Step (1), aiding patriarchy in the process.

We may want to imagine the aphallophobic matrix as concentric layers of defense mechanisms against the attacks on hegemonic masculinity from its dangerous margins (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 APHALLOPHOBIA. © B. Scherer, 2018.

Normative-oppressive masculinities are ever vulnerable and contested. The claimed superiority of masculinity above femininity means that maleness is in constant need of reasserting (Kimmel 1994), in a state of constant, struggling becoming rather than in state of simply relaxing into Dasein (being-in-time). Therefore, oppressive masculinities need to reassert themselves in sexism as reinforcing both binary and hierarchy. The link between misogyny/sexism and homophobia has long been established (e.g. see Pharr 1997; Rosky 2003; Anderson 2009): the abjection of atypical masculinities and femininities as blurring the binary distinction in the heart of patriarchy and the abjection of non-normative gender performances become necessary within the same framework of the sexist reinforcement of male hegemony. The blurring of the binarist construct of sex/gender and their pursuing of normativities includes the rejection of intra-gender desire and sexualities as transgressions and undermining binary-stabilizing gender norms and roles (domination/submission, penetration/reception). In its arguably most brutal form, aphallophobia expresses itself in transphobia and intersexism: the occurrence of non-, inter-, and trans-binary individuals with regard to biological sex and cultural gender is perceived as a frontal assault on the validity of the sex/gender binarism that lies at the heart of male privilege. Transition becomes the paradigmatic transgression: “atypical” intersex bodies are regularly surgically violated in infancy in order to achieve (in most case the de-phallic and “inferior”; i.e. female) gender binary status; in the case of trans* people, any “male-to-female” transition must be interpreted within the patriarchal-oppressive script as the abdication of the (superior) phallus, while any “female-to-male” affirmation must be interpreted as a usurpation of the phallus. Finally, nonbinary, androgynous, genderqueer, gender-fluid, and gender-rejecting identity performances appear as anarchic subversions of the phallus. Trans* invades the “ontological security” (Giddens 1991) implicated in cis-hetero-phallic patriarchy and becomes the nucleolic focus of threatened hegemonic masculinity.

Ironically, “TERFs” (so-called trans-exclusionary radical “feminists”—from Mary Daly to Germaine Greer to the emergence of the contemporary vocal minority of “feminists” who oppose trans* rights) employ a similar argument in order to refuse space and voice to transwomen; they claim that transwomen usurp and invade women (or “womyn”: female-born women)-only spaces and embodiments. Yet it is not only the inclusion of gender diversities that has divided feminisms. The fundamental binary view on gender comes with dogmatic positions that have successfully filtered into policies and laws. The rise of “carceral feminism” (Bernstein 2010), neo-abolitionism (Wylie 2017), neo-puritan moral panics (Goode and Ben-Yehuda 2009), and “feminist violence” (Zalewski and Sisson Runyan 2013) is, unfortunately, not an imaginary phenomenon: feminist-derived forms of thought-policing, virtue signaling, reductionist moralizing, and, yes, oppression and systemic violence do exist. Harmful dogmatic positions include the “perpetual victimhood of women” in the bio-political and bio-legal systems; the consequences of this particular gender-essentializing political mytheme include, for example, rendering invisible (and even ridiculing) non-(cis-)female victims of intimate-partner and sexual vi...