- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

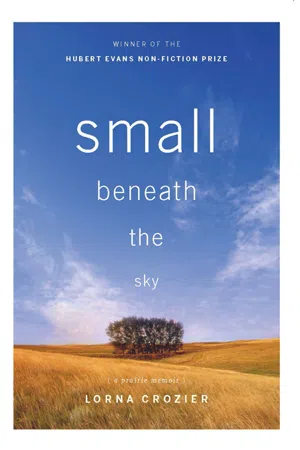

Small Beneath the Sky is a tender, unsparing portrait of a family. It is also a book about place. Growing up in a small prairie city, where the local heroes were hockey players and curlers, Lorna Crozier never once dreamed of becoming a writer. Nonetheless, the grace, wisdom, and wit of her poetry have won her international acclaim. In this marvellous volume of recollections, she charts the geography that has shaped her character and her sense of home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Small Beneath the Sky by Lorna Crozier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

my mother for

a long time

a long time

AUNTIE GLAD lived across the street in a bungalow that could have been the twin of my mother’s. The same white siding, the same slope to the roof, the same narrow verandah. At ninety-five, she was the eldest in their family, and of seven siblings, she would be the last one left. Like my mother, Glad was severely independent, living alone since her husband had died over thirty years before. Recently, though, she’d begun losing track of time. The day of the week, the year, even the seasons seemed to slide into one another like water pouring from the pump into a half-full pail.

During my aunt’s years of canning and preserving, on the labels of her jars of fruit, jams and jellies, she’d note in pen and ink a significant happening from the day. On the glass jar glowing a burgundy-red in her cupboard, the label said, “August 12, 1999, Chokecherry Jelly. Frieda Fitch broke her hip.” On a taller jar of saskatoons on her cellar shelf, she’d printed, “July 21, 1980. Jock MacPherson died in bed,” and on a stubby sealer, brown inside, “September 8, 1972. Mincemeat. Russia 5, Canada 3.” She’d also kept journals over the years, starting in 1932 when she was a young woman. Most of the entries were as brief as her labels, the thin books full of the weather and simple daily tasks. “Went to the Yuricks for water today. Stopped for coffee.” Or, “Hens not laying. One egg this week. Rusty and I played crib for it.” Or, “Had a bath,” an event important enough to record every time. In the journal for 1948, on May 24 she wrote, “Peggy had a baby girl”—those five words alone on the page, no other entry for the rest of the year about the newest member of the family. I was that baby. My aunt’s unadorned notation marked the written beginning of my long relationship with her, with my mother and with words.

HOW CLEARLY the scene unwound, burned into the oldest part of my brain. Going down the wooden steps into our dirt cellar (was I four?) to get a jar of pickles. The descent came back detail by detail—my little-girl shoes, the sundress I wore out to play, my hand clutching the smooth railing. I had to be careful; there was a gap between each step where the dark poured out. The cellar was an open mouth dug into the earth. Outside, there was a small wooden door you could lift if you were as big as my brother and crawl inside and no one would ever find you.

Alkali grew through the cellar’s damp walls like a poisonous white mould. And the smells were funny there. Something sweet, something rotten, something growing. The bare light bulb burned above me, its long string hanging just within my reach. Water made noises in the cistern even when it wasn’t raining and nothing inside its tin walls should have been moving. I was sure I heard the lapping of waves, as if a blunt, fishlike creature had surfaced and was blindly swimming for the light.

To get the pickles, I had to walk across the dirt floor on the sheet of cracked linoleum, past the bin where potatoes stretched their thin arms through the slats to pull you in. The only good thing was the shelves loaded with preserves, the crabapples and saskatoons casting their own soft glow, ripe sun trapped inside glass. I was on my toes, my hand reaching for the jar, when suddenly I heard a scuffle near the bin. A lizard scuttled from the dark, then stopped in the middle of the floor and stared. I ran to the steps and screamed for Mom. Down she came, apron flapping, a butcher knife in her hand. She stepped on the lizard’s tail, stabbed it in the back, opened the furnace door and threw it in. How fierce she was, how strong! This is my first memory, I told Patrick, the first picture of my mother. All my life I’ve carried this image of her bravery, her lack of hesitation, the strange blood on her hands.

“But Lorna,” Patrick said, “it wouldn’t have been a lizard. They aren’t any in Saskatchewan. It was probably a salamander. Remember you were four and it would’ve looked big to you. Your memory’s playing tricks.”

How I argued for memory, the green body writhing on the knife, the boldness of my mother’s hands, the flames dancing on the black door of the coal furnace as she swung it open on its big hinges and slammed it shut. A lizard. At least a foot long.

“Phone your mother,” Patrick said. “Ask her how big it was.”

I dialled the number I’d been dialling all my life. “Mom,”

I said, “remember that time in the cellar? You stabbed a lizard in the back and threw it in the furnace?”

“What are you talking about?” she said. “You must’ve been dreaming. I never would’ve done that.”

Her response stunned me into silence.

She must have forgotten, I thought, or her battle with the dragon was so frightening she’d had to bury it deep in her mind where she couldn’t call it back. Nothing I said on the phone convinced her.

“You were always such an imaginative child,” she said.

That scene in the cellar, as much as anything in my childhood, shaped how I saw my mother—her courage, her invincibility. Years later I came across a passage from the Talmud. If I’d known it then, it might have made me feel better when she insisted I’d been dreaming. I could have replied, “I am yours and my dreams are yours. I have dreamed a dream and I do not know what it means.”

THE MAY of her eighty-eighth birthday, my mother was not strong enough to clean her windows. By July she couldn’t pick her peas or dig potatoes, though only two months earlier she’d planted a garden huge enough for two big combines to park side by side. I thought a good death for her would be to fall between the rows; when she didn’t answer the phone that day, a friend would find her among the tall peas. She was not strong enough to walk the half block to the park as she had done the week before, leaning into me, not strong enough to make her meals or to pull the wide blue blinds down in the morning in the verandah to keep out the sun. One day she told me she couldn’t dress herself. She perched on the edge of the bed, and I asked her to raise her bum so I could pull on her underwear, then the summer shorts she’d chosen for the heat. She didn’t need to tell me she was strong enough to die. I could see it in her face, in the brown hand that clawed my forearm when she pulled herself slowly to her feet. She was not just getting off the bed but starting her difficult climb, rung by rung, up the invisible ladder to the sun.

ONE REASON she was ready to go, my mother said, was that she could finally leave her sister Glad behind. What a relief! Glad had been a burden since she’d moved in across the street, Mom having to do her bills, mail her letters, buy her groceries and sometimes cook her meals. That April, even though my mother’s illness had sapped her of energy, she’d done Glad’s spring cleaning after she’d finished her own. And Glad was never appreciative. All their lives she’d found fault with my mother, and she’d carried her nastiness from childhood into their adult relationship. I kept telling Mom that she was too old to take care of her sister, but Glad was in her nineties, she said, and her mind was going. Over the last few years she’d had a number of mini-strokes. My mother had to remind her to go to the doctor, to see her hairdresser for her weekly shampoo, to put her meat in the fridge and throw away the moulding leftovers. People kept stealing from her, Glad told my mother: money from her wallet, an old rubber garden hose, her hearing aid and glasses, one day a sheet of oatmeal cookies she hadn’t baked. Mom said her sister had always surmised things. Childless, Glad explained to the hairdresser that her mother had sewed her up when she turned eleven, stitched her shut with a long red thread. The gypsies showed her mother how to do it. “Grandma was a good sewer,” Mom said to me, “but she didn’t do that.” Glad’s husband was sterile because he’d had the mumps. The town doctor had warned her of the problem before the wedding and advised her to back out before it was too late.

When they were kids, Glad kept her siblings under control with a horsewhip and tattled to their strict father when he came in from the fields for supper. Because of her snitching, usually one of them, though the meal was sparse, had to go without the rice pudding Grandma made for dessert every day of the week. Not even any raisins in it, just white rice and milk with cinnamon sprinkled on the top. Grandma baked it in the oven in the big enamel pan they used later to wash the dishes and, once a week, to wash their hair.

“WHEN I SEE your dad again,” Mom said, “we’re going to go skating.” So far, that was the most astonishing thing she’d said about her readiness to go. After all they’d been through, after all the difficulties his drinking and selfishness had caused, that was what she saw them doing when they met sixteen years after his death. I caught a sob in my throat when she told me that. When she saw Dad again, they were going skating.

MY MOTHER never spoke badly of her parents. Her silence was a pact she’d signed in blood, like many of her generation. No use complaining; there were worse off than you. She’d told me about being sent at five to the farm down the road, to live with the Winstons. For the next ten years, she was their slave child.

One of her tasks was to pull weeds from the field where the Winstons had planted their crop. When we drove near Success one August, my mother pointed at the yellow flowers in the ditch. “See,” she said, “they’re sunflowers and they grow in the gumbo.”

“I think they’re brown-eyed Susans, Mom.”

“I don’t care what you call them. I hate them, they’re what I had to pull out day after day in the heat.” I’d never heard that detail of her story before.

There’s a photo of my mother around age six with her siblings and her parents. It must have been taken one of the times she was allowed back home. Behind them, the dust settles just for the time it takes the camera to catch the scene and its gawky, bird-boned children. Her hair’s “straight as a board,” her dress shapeless. She has no shoes, same as her brothers and sisters, and she doesn’t smile. She never smiles in any photograph taken of her and her family.

“I must learn a new way of weeping,” the Peruvian poet César Vallejo wrote. For now, I thought, the old way would have to do.

ONE OF THE sweetest memories from my childhood is the smell of freshly baked bread wafting through the porch door as I came into our yard from school. Mom learned to bake her bread at the Winstons. Too short to punch it down, she stood on a stool at the kitchen table, her fists pummelling. If the bread didn’t turn out, she didn’t get any supper, and after the others had eaten and she’d done the dishes, she had to start again, mixing the sugar, water and yeast, adding the liquid to the big bowl of flour, staying awake until the bread had risen, punching it down, letting it rise a second time, punching it down again, then putting it in the oven, and finally, the house in darkness, sliding its pans onto a wooden board to cool. She kept herself from sleeping by standing up, trying to balance on one leg, then the other. Even then, she dozed off like a horse on its feet, and the bread would have burned if something hadn’t made her jerk awake. Mrs. Winston’s yelling down the stairs, the tolling of the hours from the tall clock in the hallway, the image of her mother waking her up in the early morning to pick berries before the sun got too hot.

THE FAMILY took care of Mom at her house in Swift Current. We were a small group, just my brother, Barry, his wife, Linda, Patrick and me. We took turns coming from our homes, theirs in Cochrane, Alberta, and ours on Van–couver Island. Everything had happened fast. I’d arrived at her house on June 5, planning to drive her to her grandson’s wedding in Calgary. On June 7 in the morning she had a colonoscopy, part of a regular checkup, which revealed a large tumour; by the afternoon we found out the cancer spotted her liver and had spread to her lymph nodes; the next morning she was under the scalpel. When the doctor told her he had to operate to remove part of her bowel, she said, “Oh, but we have a wedding to go to.”

“We’re not going to the wedding now, Mom,” I said. It was the first time during her illness that her eyes had looked frightened, their blue blurred like startled water.

I was alone with her the week of her surgery. They wanted to take out the tumour, or at least part of it, to prevent the bowel from blocking completely. Pre-op, she told the nurses the last time she’d been in the hospital—the same hospital, as it turned out—was to give birth to me. Maybe because she’d been amazingly healthy all her life, even when she’d started losing weight and energy we thought she’d get better. Back in the winter she’d been diagnosed with diabetes; she’d be her old self soon, we believed, back to aqua exercises three times a week, meeting with her friends and single-handedly running a house and a big garden once her sugar levels got sorted out. No one, including her, had expected cancer. “At least I know what I’m going to die of,” she said. “I always wondered about that.”

Afraid I might never see her again, I sat with her before the operation, held her hand and choked out the words, “You are my shining light.”

“And you’re still my little girl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- First Cause: Light

- First Cause: Dust

- First Cause: Wind

- Common Birds of Canada

- By and by

- The Drunken Horse

- Milk Leg

- First Cause: Mom and Dad

- Spoilt

- Familiar as Salt

- My Soul to Keep

- Crazy City Kid

- First Cause: Rain

- First Cause: Snow

- First Cause: Sky

- A Spell of Lilacs

- Fox and Goose

- Tasting the Air

- Spit

- Light Years

- The Only Swimmer in the World

- As Good as Anyone

- Lonely as a Tree

- First Cause: Insects

- A Very Personal Thing

- Perfect Time

- Dark Water

- First Cause: Grass

- First Cause: Gravel

- First Cause: Horizon

- The Diamond Ring

- Till Death Do Us Part

- My Mother for a Long Time

- Not Waving But Drowning

- First Cause: Story

- Acknowledgements