- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When people imagine 1920s Chicago, they usually (and justifiably) think of Al Capone, speakeasies, gang wars, flappers and flivvers. Yet this narrative overlooks the crucial role the Windy City played in the modernization of America. The city's incredible ethnic variety and massive building boom gave it unparalleled creative space, as design trends from Art Deco skyscrapers to streamlined household appliances reflected Chicago's unmistakable style. The emergence of mass media in the 1920s helped make professional sports a national obsession, even as Chicago radio stations were inventing the sitcom and the soap opera. Join Joseph Gustaitis as he chases the beat of America's Jazz Age back to its jazz capital.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jazz Age Chicago by Joseph Gustaitis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

JAZZ AND THE SPIRIT OF THE TIMES

On December 23, 1921, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered a new composition—Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomime. The reviewers loved it. One commented that the composer “has elevated jazz to a position in the great orchestra.”7 It was the first classical composition to use the word “jazz” in its title, and it came a little more than two years before George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, usually considered the first concert work to adapt jazz to the classical idiom.8

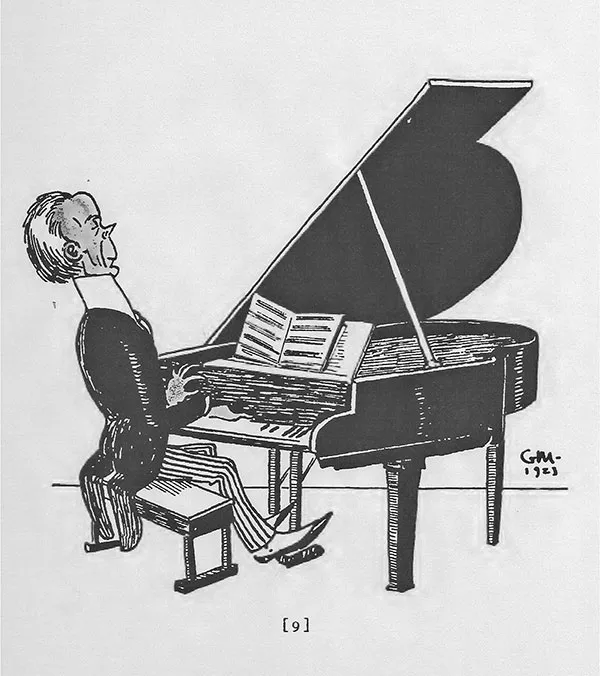

The composer of Krazy Kat was a Chicagoan named John Alden Carpenter (1876–1951). Carpenter’s first notable composition was the popular Adventures in a Perambulator (1915), a tonal depiction of a day in the life of a baby. Two years later, he presented his Piano Concertino, which has been called “a landmark in American concert music” for its incorporation of ragtime and Latin rhythms.9 After Krazy Kat came another jazz-infused ballet, Skyscrapers (1926). The reviews of Skyscrapers were enthusiastic; one hailed its description of the “vital forces” of “our distinctive national life.” Given that Skyscrapers celebrates the towers of Carpenter’s hometown, he might be thought of as not only a jazz composer but also as the first (and probably only) Art Deco composer.

LOOKING THROUGH THE LENS OF JAZZ

Carpenter’s era is sometimes known as the “Roaring Twenties,” but it is probably better known as the “Jazz Age,” a term coined by F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1922. The cultural history of Jazz Age Chicago includes such new forms of expression as radio, movies, pop music, sports and mass-circulation magazines and newspapers (Krazy Kat was based on a comic strip). By thinking of “jazz” as not only a type of music but also as a cultural sensibility, the term can apply to other phenomena. For example, the term jazz moderne became current as people, when confronted with Art Deco’s zigzags, instinctively thought of jazz. The futurist architect Le Corbusier, for example, remarked that skyscrapers represented “hot jazz in stone and steel.” The Black painter Archibald Motley Jr. created genre scenes depicting Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, and when we see a Motley painting of a cabaret, we need to imagine jazz playing in the background. The art historian Richard J. Powell has called Motley “the quintessential jazz painter, without equal.”10

JAZZ AT THE CONCERT HALL

Chicago’s own John Alden Carpenter, shown in a caricature by artist/writer Gene Markey, was the first composer to use jazz in classical music—not George Gershwin, as is commonly said. Author’s collection.

A relationship between jazz and the American spirit is the subject of a collection of essays edited by Robert G. O’Meally titled The Jazz Cadence of American Culture; in the introduction, O’Meally, the author, says “that in this electric process of American artistic exchange—in the intricate, shape-shifting equation that is the twentieth-century American experience in culture—the factor of jazz music recurs over and over and over again: jazz dance, jazz poetry, jazz painting, jazz film, and more. Jazz as metaphor, jazz as model, jazz as relentlessly powerful cultural influence, jazz as cross-disciplinary beat or cadence.”11

The energy of the Jazz Age was nervous, optimistic and even frivolous. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that the era began in the spring of 1920 in a mood of “general hysteria.” Americans were riding a wave of innovation and saw no reason it should stop. For many, jazz meant change. As one analyst has written, “For many Americans, to argue about jazz was to argue about the nature of change itself.”12 Another aspect that reflected this energy was the speed of that change. As music historian Rob Kapilow has written, “We tend to think of the twenty-first century as a time when new technologies make older ones obsolete at dizzying speed, but the pace of invention in the 1920s and ’30s makes contemporary innovation seem slow by comparison.”13 The songwriter Irving Berlin, who knew as much as anyone about the music of the time, said jazz reflected the “rhythmic beat of our everyday lives. Its swiftness is interpretive of our verve and speed and ceaseless activity.”14 The people of the era weren’t ashamed of indulging in a little zaniness, and one indication of their playful energy was the enthusiasm with which they welcomed fads or crazes. Using the word craze to describe something of intense, short-lived popularity was a creation of the Jazz Age.15 Among these fads were flagpole sitting, crossword puzzles, marathon dancing and Mah Jongg.

The enthusiasm for sports in the 1920s also reflected a jazz sensibility. Many of the sports stars brought something different, something more “energetic” than what had been customary. Babe Ruth is the most obvious example, but Lars Anderson, the biographer of football star Red Grange, spoke of Grange’s “jazzlike improvisation on the field.”16 Historian Davarian L. Baldwin argues that the style of today’s basketball and football is derived from the jazz culture of Chicago’s Black community on the South Side:

The jazz music accompaniment that drew fans to the unproven commodities of basketball and professional football directly influenced the style of play. The Black “shimmy” and the appropriately named “jukin” running style on the gridiron were powerfully influenced by the “rabbles” at half-times and musical rhythms during the games. Some assert that the transition of basketball from primarily a set-shot to a jump-shot game was heavily influenced by the after-party jazz music contexts of the Savoy Ballroom, with their “air-walking” lindy hop dancers. The jazz parlance “hot playing” was used as early as 1919 to describe the sped-up “racehorse” style of basketball performed by Virgil Blueitt and the Wabash (YMCA) Outlaws.17

The music critic Winthrop Sergeant contended that jazz was a key indication of the split from European culture that Americans achieved in the twentieth century, and he argued that the jazz spirit, with its “feverish activity,” is quintessentially American. “It is not surprising,” he wrote, “that a society that has evolved the skyscraper, the baseball game, and the ‘happy ending’ movie, should find its most characteristic musical expression in an art like jazz.” He argued that Americans value a sense of incompleteness, because the typical American is an “incurable progressive.” John A. Kouwenhoven, a prolific writer on American culture, argued that Chicago’s urban skyline of skyscrapers gives the impression of unity in diversity—“Once steel cage construction has passed a certain height, the effect of transactive upward motion has been established; from there on, the point at which you cut it off is arbitrary and makes no difference.” Incompleteness is central to the aesthetic. Americans, he says, favor things that are in development, that are “open-ended”—like an urban street grid in which thoroughfares have no fixed termination, a skyscraper or a performance by a jazz ensemble.18

Finally, in the 1920s, jazz, along with cigarettes, short skirts and bootleg alcohol, was considered a means of rebellion—against European standards of culture, against Victorian morality, against parental mores and “small-town” values. When critics—both Black and White—denigrated jazz as vulgarity practiced by incompetents, that only made the music more attractive to the flappers and their beaus. As the voice of a new generation, jazz brought a lot of cultural weight along with it and became the sound and spirit of the age that spanned the interwar years.19

THE FIRST MODERN DECADE

Today, we relate to the citizens of the Jazz Age because they were like us. The 1920s was an era in which Americans created and came to share a national pattern of preferences and leisure and when consumption came to characterize the American way of life. The 1920s was the “decade in which Americans firmly embraced a new manner of living.”20

The British novelist L.P. Hartley famously wrote, “The past is a foreign country.” But if we were to travel back in time to the Jazz Age, we wouldn’t find it especially foreign. People in the 1920s had electric lights, flushable toilets, electric commuter trains and automobiles—in 1920 there were 9 million cars in the United States, and in 1930, there were 23 million cars and four out of every five families owned a car.21 People rode on rapid transit systems, worked in offices in tall buildings with elevators and typed on keyboards. They had records and pop music, they danced in clubs, they went to restaurants and movie theaters and they were big sports fans. Radio was creating a national celebrity culture, and they loved sitcoms and soap operas. Advertising was unavoidable, largely due to radio, newspapers and magazines. Even air travel was becoming possible—Chicago’s Midway Airport opened in 1926. Finally, a youth culture was emerging. Movies, sports, automobiles and jazz appealed to the young, and stories were already circulating about teenagers being addicted to telephones. The median age was only twenty-four, and two-thirds of the population was thirty-five or younger.22

The initiation of a mass consumer culture in the Jazz Age brought “standardizing and flattening processes” that “eroded regional distinctions.”23 Forces like movies, radio and mass-circulation magazines encouraged a sense of a common national identity. When an occurrence, such as a hero’s welcoming parade or a boxing match, was broadcast live on the radio, the whole country shared it simultaneously. “For the first time in the nation’s history, one could realistically talk of a national audience for a political, sports, or other event.”24

Many of today’s supermarket staples were introduced in the Jazz Age; among them were Wonder Bread, Peter Pan peanut butter, Welch’s grape jelly, Butterfinger candy bars, Wheaties, Rice Krispies, Land O’Lakes butter, Oscar Meyer wieners, flavored yogurt, Velveeta cheese, La Choy foods, Popsicles, 7UP and Sanka.25 Nonedible products included Scotch tape, Listerine, Band-Aids, Drano, Kleenex and Brillo.26 And the list goes on and on—customers were buying these items in supermarkets. People were also consuming fast food—the White Castle hamburger chain opened in 1921, and Howard Johnson’s followed four years later. Women no longer had to sew their own clothes—they bought them in stores or ordered them from catalogs. Because of the low prices, fashions were remarkably egalitarian. As the social theorist Stuart Chase explained at the time, “Only a connoisseur can distinguish Miss Astorbilt on Fifth Avenue from her father’s stenographer or secretary.”27 It took only a year or two for designer fashions to travel from Paris to the Chicago-based Sears catalog: “For as little as $8.98, a young farm girl living miles outside Duluth, Minnesota, could purchase a silk flat crepe skirt and chemise of the latest flapper style; another 95 cents bought her a real ‘Clara Bow’ hat to match.”28 Women were also becoming keen users of cosmetics; in 1927, they spent nearly $2 billion on cosmetic products.29 Lipstick became fashionable with the invention of the swivel-up tube in 1923. The popularity of makeup created a new profession and a new word—beautician.

Women began shaving their armpits, a practice made necessary by the revealing clothes and vigorous arm actions of the new dances. The downside of the fashion mania was a concern about weight. The flapper styles stressed slimness, and critics began lamenting the pressure being put on young women to shed pounds while tobacco companies promoted cigarettes as a way of staying thin. It was in the Jazz Age that Americans began their obsession with dieting.

As for modernism in the arts, by the Jazz Age, Chicagoans had gro...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Making America Modern

- 1. Jazz and the Spirit of the Times: Interlude: The Flapper Capital

- 2. A Visit to Jazz Age Chicago

- 3. Beer Flats and Bathtub Gin: Dodging Prohibition: Interlude: A Chicagoan in Paris

- 4. Perpetrators, Prosecutors and Public Enemies: Organized Crime: Interlude: Gangster Funerals

- 5. Zigzags, Bungalows and Streamlining: Building a City Moderne: Interlude: The Women’s World’s Fair

- 6. Jazz Capital of the World: Interlude: Jazz Me Blues

- 7. “Guggle and Glub”: The Chicago Art Scene: Interlude: Harry Keeler’s Naughty Magazine

- 8. Games with a Jazz Beat: Chicago Sports in the Golden Age

- 9. The Rainbow City and the End of the Jazz Age

- Chicago Timeline: 1919–1933

- Notes

- About the Author