- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The ways in which urban areas have evolved over the past 100 years have deeply influenced the lives of the communities that live in them. Some influences have been positive and, in the UK, people are healthier and live longer than ever before. However, other influences have contributed to health inequalities and poorer well-being for some in society. Today many people suffer as a consequence of 'lifestyle diseases', such as those associated with growing obesity rates and harmful consumption of alcohol. The threat of these health issues is so acute that life expectancy of future generations may begin to decline.

Healthy Cities? explores the ways in which the development of the built environment has contributed to health and well-being problems and how the physical design of the places we live in may support, or constrain, healthy lifestyle choices. It sets out how understanding these relationships more fully may lead to policy and practice that reduces health inequalities, increases well-being and allows people to live more flourishing, fulfilling lives. It examines the consequences of 'car orientated' design, the 'toxic' High Street, and poor quality, cramped housing; and the importance of nature in cities, and of initiatives such as community gardening, healthy food programmes and Park Run. It questions whether Heritage is always conducive to well-being and offers lessons from holistic and innovative programmes from the UK, North America and Australia which have successfully improved community and individual health and well-being.

Healthy Cities? explores the ways in which the development of the built environment has contributed to health and well-being problems and how the physical design of the places we live in may support, or constrain, healthy lifestyle choices. It sets out how understanding these relationships more fully may lead to policy and practice that reduces health inequalities, increases well-being and allows people to live more flourishing, fulfilling lives. It examines the consequences of 'car orientated' design, the 'toxic' High Street, and poor quality, cramped housing; and the importance of nature in cities, and of initiatives such as community gardening, healthy food programmes and Park Run. It questions whether Heritage is always conducive to well-being and offers lessons from holistic and innovative programmes from the UK, North America and Australia which have successfully improved community and individual health and well-being.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Healthy Cities? by Tim Townshend in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Stadtplanung & Landschaftsgestaltung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Lessons from History: Special Places to Everyday Spaces

In this chapter, we trace 2,500 years of human history, from ancient Greece to the end of modernist-inspired planning in the late 20th century, and reflect on key themes that run through this period.

Early beginnings

The notion that certain places are infused with special properties that are good for health is a very ancient one and transcends cultures across the globe. From the 5th century BCE onwards, for example, the Greeks built an entire city dedicated to healing – Epidaurus, in the eastern Peloponnese. It was built over many generations and at its height, Epidaurus could house several thousand visitors recovering from illness. People travelled from all over Greece to visit the city, though of course this would only have been an option for the relatively wealthy.

The natural landscape was very much integral to the original city, and Epidaurus was sometimes referred to as the ‘sacred grove’ because the buildings were surrounded by trees (Alt, 2017). The city contained a variety of buildings, including temples where ritualistic purification and healing were performed. However, many structures were secular, designed for exercise and entertainment (Fig.1.1). As embodied by the city, the healing process for the ancient Greeks included mental, spiritual and physical (bodily) needs.

Figure 1.1

The amphitheatre at Epidaurus, built for entertainment and mental stimulation, showing the relationship to the landscape beyond

Water and healing

Spas

A key part of the curative processes at Epidaurus involved washing and cleansing. Water, of course, is the most essential element of life and humans can only survive a few days without it. Over millennia, our relationship with water has also been multifaceted. Used as a source of food and for transportation, it has also been a source of spiritual inspiration. To the ancient Greeks and Romans, sources of water, such as springs and rivers, had their own distinctive deities. Even today, most major religions include water-based ceremonies as part of ritualistic purification.

In Europe, the notion of the healing properties of water was developed by the Romans, who believed that different temperatures and mineral content could be utilised in different cures. For example, sulphur springs were believed to relieve muscle weakness, while alkaline springs were recommended for tuberculosis (Jackson, 1990). In the 1st century CE, during the Roman occupation of Britain, the Romans developed an extensive water-based spa at Bath, Somerset, based on a much more ancient sacred Celtic site (Cunliffe, 1984). This flourished until the Romans left Britain (around 410 CE) when Bath was partly abandoned and knowledge pertaining to the curative properties of water was lost. However, during the Italian Renaissance in the 15th century, water cures again began to be taken seriously, although it took another 200 years for physicians in England to embrace this knowledge. It was during the Georgian period, therefore, that taking the waters at Bath once more became a fashionable cure for a range of ailments.

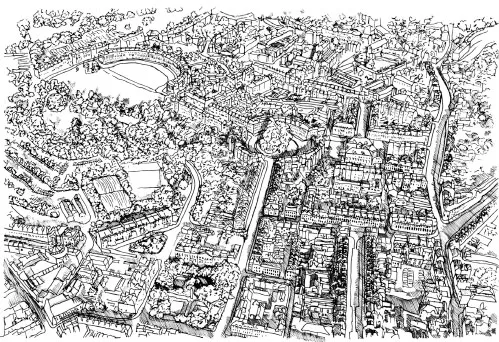

Figure 1.2

A bird’s-eye view of Bath – an embodiment of 18th-century ideas of healthiness

Bath’s prosperity was driven by a serendipitous coming together of then contemporary medical advice; wealth, provided by Ralph Allen who owned local limestone quarries; fashion, provided by Beau Nash, a celebrated ‘dandy’ associated with the city; and architecture, designed by John Wood the Elder. Wealthy visitors flocked to the city, not just to take the waters, but to go to the theatre, socialise and gamble. The city therefore catered for visitors’ physical, mental and social needs, rather like a Georgian version of Epidaurus.

Symbolic reference to health, however, was also embedded in the very physicality of the city. The architectural set pieces of Bath − Queen Square, The Circus and The Royal Crescent (Fig.1.2) − are a masterclass in order, proportion and, importantly, harmony between buildings and planting/landscape. This balance was thought to reflect that of the cosmos and was deemed essential for physical and mental health to flourish.

Coastal resorts

Tuberculosis – commonly called ‘consumption’ – was the number one killer of Britons for most of the 19th century and there was no cure. Medical opinion at the time was that such diseases were transmitted by ‘miasma’ – foul-smelling air that built up in the narrow courts and alleys in cities. Doctors suggested that consumptives needed air that was fresh and well circulated, and seaside resorts were a preferred source (Morris, 2018).

Sea bathing also became increasingly popular from the mid-18th century onwards. Again, this was encouraged by prominent physicians, who recommended both submersion in, and drinking of, seawater and proclaimed that saltwater cures were superior to those provided by inland spas. These factors led to the growth of seaside towns such as Bournemouth, Torquay and Hastings, greatly assisted from the mid-19th century by the rapid expansion of the railway network.

Water and harm

… we have then quite sufficient data to account for the surplus mortality … in consequence of the floods from the Aire which, it must be added, like all other rivers in the service of manufacture, flows into the city at one end clear and transparent, and flows out at the other end thick, black, and foul, smelling of all possible refuse.

Engels ([1845]1987)

The story of water and health is not, however, an entirely positive one. During the industrial revolution in Britain there was a dramatic change. Many industrial processes required vast amounts of water, and waterways were also used to transport goods. The river- and canal-sides of major cities became lined with warehouses, mills and works. Industries such as textile manufacture and tanneries poured vast quantities of noxious, unwanted chemicals straight into the river system, where they mixed with human and animal waste. As there was little control over the flow of water, houses near the banks were often inundated with the poisonous content of the watercourse. As a result, and as observed by Engels, rivers were basically open sewers and implicated in the high rates of mortality of those who lived near them.

Consequently, in the 19th century only the most desperate would live next to most urban watercourses, though working people generally had little choice about where they lived. The rapid urbanisation that occurred in 19th-century industrial towns and cities led to appalling housing conditions which facilitated the spread of deadly diseases such as cholera. However, this was also a period of laissez-faire economics, and state intervention was regarded as highly suspicious by the powerful in society. Therefore, for several decades, there was little official response.

Gradually, however, there was an increasing recognition that the situation could not go on. In 1832 a major cholera outbreak killed large numbers of people and the concept of ‘public health’ gained momentum. In 1840, the British government set up a parliamentary committee to report on the health of towns. This was the beginning of a series of official reports, as well as treatises written from a philosophical, or political, stance (Engels, [1845]1987). One of the most significant was Edwin Chadwick’s report on the sanitary conditions of the working classes (Chadwick, [1842]2012). This revealed, for example, that the average life expectancy of a labourer in Liverpool was a truly appalling 15 years. Such compelling evidence could not go on being ignored.

The origins of public health

There were further cholera outbreaks in 1848–9 and 1853–4, and while miasma theory continued to hold sway, a Dr John Snow, based in Soho, London, mapped cholera cases, proving that the disease was spread by contaminated water. However, while understanding of both the problems and consequences was increasing, very little changed. Inertia in the system and a resistance to state regulation prevented action. While in 1868 the Torrens Act allowed local authorities to demolish unfit dwellings, there was no mechanism for replacement, and in some cases, this made the situation worse by increasing overcrowding in the remaining housing stock.

It was not until 1875 that the first effective legislation was introduced, in the form of the Second Public Health Act, which compelled local authorities to act. It consolidated previous sanitation legislation and required urban authorities to make byelaws for new housing, to ensure structural stability, provide effective drainage and air circulation, and establish that all houses have their own toilet. In effect it was the first urban planning act, though it was not labelled as such, and while it produced housing that was often somewhat monotonous in design, it contributed significantly to improvements in the health and life expectancy of working people.

Given the incredibly unhealthy situations found in cities, the question often arises as to whether people were forced out of the countryside into cities, or did they leave voluntarily during industrialisation? Here we begin unpicking the culturally constructed urban versus countryside debate. Many British people today have a very romantic view of the countryside; however, the truth is that in the 19th century, rural living for most people meant grinding poverty. Yes, there may have been fresh air, but there was precious little else. Cities provided opportunities – for employment, for betterment and to meet new people, perhaps to find a life partner. In other words, people were responding to a basic urge to make the most of life. While it might seem counter-intuitive to express this in terms of modern concepts of ‘well-being’, that desire of people to reach their potential can be included in the concept, as discussed early in Chapter 2 and in later discussions in this volume.

Visionaries and paternalists

In parallel to the development of the public health movement, there were series of experimental, or ‘model’, projects, which together underpin a British contribution to urban planning/design that is still influential today. Full and detailed accounts of their development are available elsewhere (see the further reading list at the end of this chapter), so what is contained below is intended as a brief summary and basis for further exploration.

New Lanark

The first water-powered mills of the industrial revolution were located in relatively rural locations and needed to attract workers. New Lanark was of this type. Established in the 1780s on the River Clyde, it was situated 25 miles south-east of Glasgow. Although initially established by David Dale, it is with his son-in-law, Robert Owen − who took over as manager, and subsequently became owner − that New Lanark is most associated.

Owen was a social reformer. His philosophy, which is still readily available and worth reading (Owen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Graham Haughton

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Lessons from History: Special Places to Everyday Spaces

- Chapter 2 Definitions and Measures

- Chapter 3 Active Lives, Active Travel

- Chapter 4 The Need for Healthy Homes and High Streets

- Chapter 5 Green Infrastructure for Health and Well-being

- Chapter 6 The Benefits and Burdens of the Past: Heritage, Place and Well-being

- Chapter 7 Towards Health-Promoting – ‘Salutogenic’ – Cities?

- Notes

- References