University

Doubtless correctly, Margaret had decided that it would be good for me to move away from home in Johannesburg. Accordingly, Bill, never-failing in his ‘connections’, managed, against the odds, to get me into a men’s residence at the University of Cape Town—residence normally open only to students who had excelled in some way at school, preferably as rugby players or cricketers. Lacking such qualifications, not even Bill’s influence could find a place for me at Smuts Hall, the men’s residence of choice. But a residence had been built for ex-servicemen on some vacant land not far from the university, eleven Nissan huts each with twenty-two rooms. The occupants of three of these huts now having graduated, they had become available for non-ex-service freshers. Quick to find residence life enjoyable, with numbers of new friends, I went to the cinema—bioscope as it was known, the bio—six times a week. As I seldom attended lectures and did no work at all, the results of tests at the end of the first term were disastrous. In July it was agreed that it might be more profitable for me to go on a trip to England with my mother.

Having now sold the house in which we had lived as a family, my mother was living in a boarding house while she looked for something smaller. We looked together, finally buying the house in which my mother died forty-six years later. Breathing fresh life into the Isipingo spiritualists’ forecasts of Armageddon, the Korean War had broken out. But now, leaving Puddums, my mother’s, highly neurotic and very vocal Siamese cat in the care of the boarding house’s German housekeeper, we set off by air for London. With the house and its upkeep gone, and some relaxation finally agreed by my uncles and Willy for my mother’s finances, such a trip had at last become financially possible. As at the time of our flight from America, there was only one class of air travel, what, I suppose, would today be first class. The return fare was three hundred and fifteen pounds, and for an extra twenty-five pounds one could have a bed, but a real bed, like the beds on a Wagon Lit or an American Pullman, two tiers on either side of the aisle, four beds in all, the bottom one the breadth of two seats and the top about four foot wide, all made private by heavy canvas curtains. Though the plane landed every five or six hours, passengers with beds remained undisturbed.

The shock of London on our arrival began with the bus ride from the airport. Nothing was as I had pictured it. The scale was both greater and less than I had imagined, greater in the seemingly endless spread of London, and less, as though everything within the spread had been compressed to Lilliputian size by what was around it. Rows of identical, unattractive houses (no freeway—an eighty mile stretch of the M1 opened nine years later was Britain’s first motorway) most decrepit and run down, many shabby, grimy, and dilapidated, squatted uncomfortably in tiny patches of often rank, untended garden. Six years of war had left the country and its people exhausted.

Fireweed and buddleia sprouted abundantly from the ruined shells of bombed out buildings. Often above pools of stagnant water, fireplaces and wallpaper still clung to an inner wall, reminders of the rooms they had once ornamented, now vanished. Grime and soot deposited by centuries of fog dulled and blackened every exposed surface, stone, brick, render or glass. The outsides of the miles of houses built of unrendered pale London stock brick were black. Only years later did washing reveal the brick’s natural, pale yellowish grey. [The picture shows a wall, one part washed the other not.] St Paul’s was black, its exterior slick and shining with soot. It remained that way until it was washed—not without protest—along with much of the rest of London in the late 1960s and early seventies. But in 1950 war had spent both the resources and the energy for renewal of this kind. All available means were employed for replacing what the war had destroyed.

American Express had booked us into the Mount Royal Hotel—it remains unchanged today under another name. Huge and undistinguished, but comfortable, it occupied a full block of Oxford Street at the Marble Arch end. The reception desk was two floors up from the ground level. During the bombing, we were told, a blast had blown a bus up, into the lobby. My mother and I each had a large room, with a bathroom and dressing room, for which we paid thirty-five shillings a day (£1.75). A locked door stood between interconnecting rooms, to be unlocked not on request, but in our case only if we could show that we were mother and son. Five years after the end of the war, meat, eggs, sugar, sweets, clothes, petrol, were still rationed. The hotel breakfast consisted of two small sausages about the size of a man’s little finger and seemingly filled largely with brown sawdust. My mother entertained Margaret’s ex-nanny to lunch in the hotel’s grill room.

At the theatre we sat in the ‘pit stalls’, seats under the balcony, for eight shillings and four pence and had a pot tea and biscuits served to us on a tray during the interval. We were at the theatre on the night Shaw’s death was announced at the interval. One night we went to the Café Royal for dinner, at the time still a smart place to dine. At the end of the meal I paid the bill. Leaving the payment on the table, we went out to take a taxi at the rank in the middle of Regent Street. As we were getting into the cab, a waiter pursued us from the restaurant his tailcoat flying carrying a tray and with a napkin over his arm. I had underpaid. Taking the bill to be 19/4, about ninety pence. I had left I suppose, about one pound and two shillings. In fact, the bill was £1:9:4, fifty per cent more—the numbers burned into my memory by my embarrassment at the time. The 19/4 had not surprised me; that was the kind of price one paid at good restaurants.

Travelling on Green Line buses or by train, we visited friends of my mother’s outside London, among them Frances Banks, previously for twenty years, Sister Frances Mary, an Anglican nun. Three years later my mother toured Greece, the Levant, Austria, and Italy with her.

After some weeks in London, armed with detailed route maps from the AA, we set off by car to tour England and Scotland. The car was an Austin A40, picked up from a garage next door to our hotel. Sent directly to Hyde Park Corner by the AA map, my driving was far from relaxed. And it rained and it rained. Hotels were dismal. Guests whispered to one another as they spooned down Brown Windsor Soup at large communal tables. Parking our car in the street overnight was not permitted and few places offered alternative parking. After some days of this, at about ten o’clock at night in Torquay, my mother always enthusiastic about spontaneous changes of plan, we decided we had had enough. We rang the Mount Royal Hotel to book rooms and set off back to London, arriving after one in the morning.

Next day we went to the American Express office in the Haymarket and arranged a tour in Europe. Two days later we were in Amsterdam. In Holland food was not rationed. At our very small Hotel de Pays Bas, elaborate dishes were cooked at the table. From Amsterdam to The Hague, then Paris. At each stop an American Express functionary stood on the station platform outside our compartment to meet us, take care of the luggage, find a taxi, and accompanied us to our hotel. Paris, only six years since being in the hands of the Germans, France had come close to being taken over by the communists. Nott until 1949, rescued by Marshall Aid from its desperate state of poverty and food and fuel starvation, physically almost untouched, had it once again begun to prosper, promiscuously displaying its beauty.

For a callow, seventeen-year-old from South Africa it dazzled. My mother knew some French, I none. But everything was left to me. It was how my mother had travelled with my father. Men, she had grown up to believe, were there to take care of things. Between me, at seventeen, and my father, in this rôle as her husband, she drew no distinction. So I found our way about, catching buses, ordering in restaurants—I ordered Barsac, not knowing it was sweet, foie de veau, not knowing it was liver. We saw Roland Petit’s ballet of Carmen, at the theatre in the Tuileries and went to the Follies Bergère. And we walked and walked.

From Paris, after a trip, sitting eight up in a second-class compartment from eight in the morning to eleven at night, we arrived in Nice. Conveyed by our American Express man to the Hotel Splendide in a back street was not at all what we had been looking forward to. Next day we transferred to the Ruhl, albeit to a room facing into the courtyard, not the front. At the time, with the Negresco, the Ruhl was one of the two greats nice hotels. June weather balmy and caressing, we ate on the hotel’s terrace. In the evenings, women walked dogs along the Promenade des Anglais, scarcely a car. In 1950 the main Promenade ran from the Hotel Beau Rivage on the east side to the Negresco on the west; beyond the Negresco, where there are now miles of blocks of flats, there were just largish but ordinary houses, scarcely a car on the road.

From Nice we went by train to Milan, where my mother found the late June heat oppressive; so we abandoned a planned tour in Italy, turning instead to Switzerland, beginning with a magical train ride to Zurich. There Clara and Enrico, with an Italian maid called Giulia and a black cocker spaniel called Zulu, were living in a flat half a mile down from the Schwanen Platz, on the shores of the lake. From there on to Lucerne, like most tourists ascending Pilatus on the funicular, and, unlike most tourists, running out of money. Cabling for a ‘letter of credit’—with credited cards still in the future, this, along with travellers’ cheques the only instruments making funds available abroad. Don’t cash your cheques at the hotel, people warned, you’ll get a bad rate; go to a bank—we waited and waited for the letter to arrive. Eating our meals at the hotel, the hotel bill mounting daily.

From Lucerne we went to Interlaken, autumn in the air. Large, old, melancholy at end of season, our hotel, waiters in tails, creaking wooden floors, smelling of beeswax and turpentine. We did a bus tour of four mountain passes, entered the ghostly blue of the Rhone Glassier cave, and took a train up the Jungfrau, three thousand five hundred metres. Back to the Ruhl in Nice, also winding down after the summer—at that time, the end of August marked the end of the holiday season when everyone went home and back to work. From Nice back to Johannesburg, to the boarding house.

The following year, the object again to get me away from home, I was sent off to Rhodes University in Grahamstown, where Anthony, one of the cleverer people I knew, had managed to fail all subjects at the end of his first year; Rhodes a moribund institution of only about six hundred students. Anthony and I did not work at all. I would sleep until lunch time, and sometimes through lunch. Several Anthony’s friends of the time went on to distinguish themselves. Somehow their abilities and application did not rub off on us. On days I woke in time, I attended lectures—wrong-headedly, instead of sticking to science, I had switched to an arts degree. In the afternoon we played golf at the local course.

With a few others, we had started a night school for the black people living in the separate ‘location’ about two miles from the town. Men would come across on foot—no buses. But the university authorities forced us to discontinue our teaching—which was achieving very little anyway—on the grounds that the people attending the school might be carrying TB or other more exotic diseases. These were the same people that cleaned our residences, made our beds, cooked our food, served us at table.

Back in Johannesburg for the July vacation, Clara and Enrico had come on protracted a visit. They had rented a house in Northcliffe, one of Johannesburg’s more distant suburbs, and Clara had set about assembling her usual coterie of varying hues and outlook; beyond-the-pale politicians, Wits’s brighter set among post-graduate students and more senior, left-leaning teaching staff, writers, aspiring poets and painters, and a group of young men and women making an expressionist film along psycho-analytic lines. How she conjured these circles remains a mystery—she replicated something like it wherever she pitched her tent; it was like pulling rabbits out of a hat. Ex officio, as Clara’s nephew, I enjoyed the privilege of inclusion in this exalted company. And, for me, it was indeed a privilege; I was seventeen, and easily impressed; I should never have met these people any other way.

Happily, Clara, years before, had been friendly with the Wits’s registrar, Ian Glyn-Thomas, a gentle, kindly man, a communist from the thirties. It was his son, Philip, who had so outraged the Bible Studies master at Parktown by saying he was an atheist. (Philip was killed the following year when he drove his car into a tree one night on his way back to Johannesburg from Pretoria.) Dear Mr Glyn-Thomas agreed to let me into Wits in the middle of the year. Overnight my life was transformed. After UCT and Rhodes, Wits was another world. Anthony, who stayed on at Rhodes, managed to fail all his subjects, as I should certainly have done myself had I stayed on with him. As this was Anthony’s second failure, he was unable to return.

South African universities at the time called for taking numbers of courses, two ‘majors’ running through all three years of the degree course. This was true of science and arts degrees. At Wits I continued with the subjects for which I had enrolled at Rhodes, English literature being one of them. University degrees in England then ran over four years, including what was called an ‘intermediate’ year, before starting the degree proper. The intermediate year was later absorbed into the school ‘A’ level year. A degree course at a South African university therefore required a year’s less study than one in England, the South African equivalent of an English degree being an Honours degree in which a single subject was taken to a higher level.

The English department at Wits ran a seminar system, four forty-five-minute seminars a week, each for a dozen or so students. It was in one such seminar that it first occurred to me that I might not be the dunce I had taken myself to be until then. Thelma Philip, one of the lecturers in whose seminar I found myself once a week, terrified me. She was clever and intolerant of imprecise thinking or expression—if you could not say clearly what you meant, it was because you did not understand what you were trying to say, a belief that I have held since as a guiding principle in science as much as its literature. Three years later, having done well in my degree, I became a tutor in the department, conducting such seminars with new undergraduates, as I pursued an Honours degree in English. Finding myself sharing a room with Thelma, I discovered how nervous she herself was whenever she entered a new class. ‘Give them three things to read,’ she said to me, when I went to take my first seminar. ‘Ask them which they think is the best and why. That usually shuts them up.’ It was invaluable advice.

Coming into my first tutorial class one morning, probably for some lunch-hour meeting the chairs had been arranged in a circle. Instead of calling for them to be re-assembled to face the dais in the normal way, I sat down in a chair myself, alongside the students. Looking younger than most of them, they took me for another student. When the time came to begin, I tried to speak. That is, I opened my mouth but failed to emit a sound. As I had not uttered, the failure had caught no ones’ attention. On my second attempt, I managed to introduce myself as the new tutor and did as Thelma had suggested. Distributing cyclostyled sheets with three passages of writing on them with which I had come prepared, I asked the class members to pick the passage they thought best, later to ask them to support their choices.

It was through the favourable way that Thelma received the little I had to say in her seminars that I began to feel some confidence, though, I’m afraid I must have been a very poor tutor. What I had failed to grasp was that, in a tutorial, it is the students who should do the work, the tutor standing simply as referee. But I was doing an Honours in English, partly because I was flattered at having been chosen as a tutor after my very poor beginning, and partly because I wasn’t sure what else to do. Having little inclination to go into the family firm, I certainly didn’t see my future as being an academic teaching English.

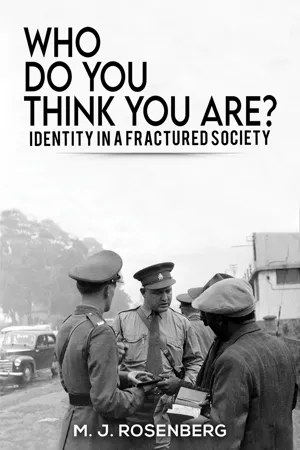

At Wits Politics was very much the driving force, certainly among the arts students. In residence at UCT no one seemed to give politics a thought, my encounters with political ideas there restricted to a remark made to me by a fellow student, a man from Southwest Africa (Namibia). An inoffensive if colourless individual, with whom I sometimes walked up the hill from our residence to attend lectures at the university. As we mounted a rocky terraced short cut, a black woman was coming towards us on our level, on her head she carried a very large, bulging cardboard box. She could neither move to a lower point, nor pass us. We had to give way. ‘In my country,’ my companion remarked in a taciturn aside as she passed, ‘we would knock that girl down.’ (The girl being a woman in her mid-thirties; an incident shadowing a similar one at school when my friend Varkevisser had been so incensed by the sight of a black woman taking a short cut through our school grounds.) At Rhodes, outside the sporty set, the views of the students I encountered tended to be reasonably liberal, though by no means radical or left wing.

But extreme left views permeated Wits. Student activities, student societies, lunch hour meetings and other events, were controlled largely by two men, both serious, dedicated communist party members, undeviating supporters of the Soviet Union under Stalin, as it then was. These were Joe Slovo and Lionel Forman, Forman freshly back from three years in Czechoslovakia, the year 1951, two years before the Slansky show trials. A third man, Harold Wolpe, a communist of the same order, appeared to act as a kind of dogsbody for the other two. Of the three, Forman was the cleverest. A small man, his angelic face and quiet inoffensive manner did nothing to betray the steely, ruthless determination of character it hid. I hardly knew him, though Joe, whom I came to know better—as much as one could a putative colonel in the KGB—was more genial and amusing, though politically no more flexible .

The Students’ Liberal Association, the SLA, provided the front behind which these three and their numerous supporters principally advanced their ideas among students, employing the widely used technique of communist parties everywhere, of what came to be called ‘entryism’: the hijacking liberal bodies to advance their own far-from-liberal aims. Highly proficient infiltrators, members of the SACP got representatives onto key committees that they would then take over from the inside. Perfected by Willi Münzenberg in the thirties in Europe and the United States, an acolyte would be planted in some key position on a committee, chairman, secretary, through whom the organisation’s activities could be directed. The SLA organised lunchtime meetings and lectures, student protests and the like. Effectively, student political activity was almost wholly controlled by the Communist Party. (In retrospect it is remarkable to me that this small coterie was able to exercise the influence it did over so much of student life.)

The annual conference of the National Union of South African Students, NUSAS, took place during the July vacation, after which followed the election of its president. The incumbent at the time was Philip Tobias, a palaeontologist already of some renown, later three times nominated for a Nobel Prize. Tobias’s liberal outlook offered nothing to the extreme left. Its supporters sought to replace him with Forman, the ferment of surrounding activity only gradually revealing itself to me. In fact, Tobias was re-elected, mainly because Wits was pretty much alone among the English-speaking universities belonging to NUSAS in having so strong an extreme left contingent in the student body.

At Wits, I made new acquaintances, many with left and communist sympathies. They did what they could to initiate me in the virtues of socialism, practised, as they told me, solely in Soviet countries. Patiently, as to a backward child, I was instructed that socialism in bourgeois countries was no more than a front for the capitalist bosses, little better than fascism and even more pernicious because it misled the masses.

In South Africa oppression of non-whites called for revolutionary change. Revolutionary change was what was sought by communists as well as Blacks, though the ultimate goals of the two were far from identical. For communists, among whom were included numbers of Blacks, the object was to make South Africa a soviet state, this, while many if not most black people, supported communism simply because it sought revolutionary change. Whites whose sensibilities extended to an awareness of the plight of the less fortunate people of colour were moved in varying proportions to indignation, guilt, frustration, a...