eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

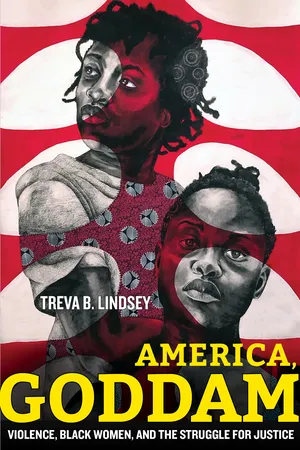

America, Goddam

Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for Justice

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

One of the Best Nonfiction Books of 2022, Kirkus Reviews

"A righteous indictment of racism and misogyny."—Publishers Weekly

A powerful account of violence against Black women and girls in the United States and their fight for liberation.

Echoing the energy of Nina Simone's searing protest song that inspired the title, this book is a call to action in our collective journey toward just futures.

America, Goddam explores the combined force of anti-Blackness, misogyny, patriarchy, and capitalism in the lives of Black women and girls in the United States today.

Through personal accounts and hard-hitting analysis, Black feminist historian Treva B. Lindsey starkly assesses the forms and legacies of violence against Black women and girls, as well as their demands for justice for themselves and their communities. Combining history, theory, and memoir, America, Goddam renders visible the gender dynamics of anti-Black violence. Black women and girls occupy a unique status of vulnerability to harm and death, while the circumstances and traumas of this violence go underreported and understudied. America, Goddam allows readers to understand

"A righteous indictment of racism and misogyny."—Publishers Weekly

A powerful account of violence against Black women and girls in the United States and their fight for liberation.

Echoing the energy of Nina Simone's searing protest song that inspired the title, this book is a call to action in our collective journey toward just futures.

America, Goddam explores the combined force of anti-Blackness, misogyny, patriarchy, and capitalism in the lives of Black women and girls in the United States today.

Through personal accounts and hard-hitting analysis, Black feminist historian Treva B. Lindsey starkly assesses the forms and legacies of violence against Black women and girls, as well as their demands for justice for themselves and their communities. Combining history, theory, and memoir, America, Goddam renders visible the gender dynamics of anti-Black violence. Black women and girls occupy a unique status of vulnerability to harm and death, while the circumstances and traumas of this violence go underreported and understudied. America, Goddam allows readers to understand

- How Black women—who have been both victims of anti-Black violence as well as frontline participants—are rarely the focus of Black freedom movements.

- How Black women have led movements demanding justice for Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Toyin Salau, Riah Milton, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, and countless other Black women and girls whose lives have been curtailed by numerous forms of violence.

- How across generations and centuries, their refusal to remain silent about violence against them led to Black liberation through organizing and radical politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access America, Goddam by Treva B. Lindsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Say Her Name

Policing Is Violence

Throughout my childhood, my car time with my dad was one of my favorite parts of the day. He would often stop by the liquor store down the street from our apartment in Northeast Washington, D.C., and get me a snack and play my mom’s numbers. I knew he was in a good mood when he got a Reese’s Cup and a bag of Grandma Utz chips. Driving down Benning Road in the shadow of the crumbling Washington Football Team’s (then known as the Redskins) stadium, RFK, you could find me and him on any given afternoon in the 1980s listening to some grown ass music. Some days it was Al Green. Other days it was Run DMC and Salt’N’Pepa. My dad loved music and exposed me to a robust Black musical tradition. Unlike some of my friends’ parents, he had an affinity for rap music. He even made sure I heard the more explicit songs.

One of those explicit songs was N.W.A.’s “Fuck Tha Police.” The first time I recollect hearing it, I was riding with my dad. I bobbed my head as Ice Cube rapped:

Fuck the police comin’ straight from the underground

A young nigga got it bad ’cause I’m brown

And not the other color so police think

They have the authority to kill a minority1

My dad looked at me as we both nodded our heads. He asked me if I understood what they were saying. I didn’t fully get it at the tender age of six. I was clear though that these “boys didn’t like the police.” He laughed and said, “With good reason.” Listening to “Fuck Tha Police” with my dad is perhaps one of the best examples of my parents using rap music to spark a conversation with me about the world around me. My dad worked in the criminal punishment system as both a corrections officer and a probation officer in the 1980s and 1990s. Knowing it was never too soon to begin educating his Black child about the realities of being Black in the U.S., he felt it was time for me to learn some harsh truths about policing.

Neither of my parents shielded me from the pulse of culture and politics, particularly the more controversial or “profane” parts. They embraced rap music and, at times, used it to teach me about race and racism in the United States. My dad knew I wouldn’t encounter “Officer Friendly,” a jovial, civil servant charged with the obligation to “protect and serve” me and my community. My dad also knew that more often than not, “protect and serve” didn’t extend to me. He didn’t want me to fear police officers per se; however, he did want me to understand the context for such an explicit callout of the folks I frequently saw patrolling my NE Washington, D.C., neighborhood. From then until I started using “cuss” words, it was “fudge the police.”

Throughout my childhood and young adulthood, I personally bore witness to the violence of policing, to the point where saying “violent policing” felt redundant. Police equaled violence from what I gathered. I saw officers violently handle unhoused people on my block. Living just a short drive from the U.S. Capitol but clearly in another world, the police harassed young folks kicking it on corners. I heard cops call Black women in my neighborhood crack whores and their children crack babies. The ease with which they showed contempt and utter disgust for my neighbors stuck with me. They didn’t see us as persons with loved ones, hopes, dreams, flaws, and struggles. We were the enemy. For me, it was never a few bad apples. Police signaled violence as much as if not more than the young boys in my neighborhood participating in the booming street drug economy of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The presence of cops in my neighborhood and, eventually, in my schools didn’t make me feel protected either. Although a lot of illicit activity went down in my poor/working-class Black neighborhood located near the corner of Benning Road and East Capitol Street, it became clear to me by the time I was a teenager that economic deprivation and stagnation and the public health crisis caused by crack cocaine was at the root of the violence I witnessed there. When I was growing up, cops seemed to be everywhere—in the parking lot in front of the corner store a couple of blocks from my apartment and at Benjamin Stoddert, the recreational center the kids in my neighborhood frequented. We couldn’t get a quick snack at the corner store or play tag without being under the watchful eye of those incessantly arresting, deriding, and assaulting folks in our community. As a child, it made me feel under attack. My folks were overdetermined as criminal.

The neighborhoods of my peers at Sidwell Friends, the elite private school in upper Northwest Washington I attended from seventh grade to twelfth weren’t surveilled in any way close to what I experienced growing up in D.C. or living in Prince George’s County, Maryland. When my mom got pregnant with me, she informed my dad that her baby was going to Sidwell. For her, Sidwell would put me in rooms and give me opportunities I would never have access to at my predominantly Black, poor, and working class–serving neighborhood school. My mom wanted to expose me to a world from which most people in my community were cut off. I wanted to go to school with my friends. I also thought I would never fit in with these “rich white kids” who lived west of Rock Creek Park, an invisible divide between the haves and have nots in a then–Chocolate City.

Most of my Sidwell folks lived in either affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods or historic, “old money” Black neighborhoods. When I got to Sidwell, I was in awe of how big my peers’ houses were. Some of them had staff. Others mentioned vacation homes. Summer was both a verb and a noun for my peers whose primary and secondary residences were in some of the most expensive zip codes in the U.S. Some of my Sidwell friends were oddly curious about where I lived. In eighth grade, a white girl asked me “if I worried about getting shot every day.” I laughed nervously and told her I was more worried about cute boys and fly clothes than getting shot. I tried to find ways to connect with my new peers, but some of their questions and what I’d seen growing up made it abundantly clear that we lived in different worlds.

Funny enough, I saw a lot of illegal drug use at high school parties thrown in affluent neighborhoods, but guess where I could always find the police? Not to dry snitch or anything, but in high school I saw white kids do everything from mushrooms to cocaine. Although a lot of my private school peers just engaged in heavy drinking and some occasional weed, drug and alcohol consumption were weekly activities. A few of their parties got broken up by police. There were a couple of memorable nights where they even got citations for underage drinking. For the most part though, their neighborhoods weren’t policed. They faced little to no consequences for seemingly clear violations of the law. If anything, the police gladly looked the other way and considered their behavior “youthful transgressions.” They were never in danger of being seen as criminals. By my sophomore year at Sidwell, I came to understand that there were those who police committed to protecting and serving. Then there was us, the targeted and criminalized.

One of the other defining moments that shaped my perception of policing occurred before I arrived at Sidwell—the beating of Rodney King. My parents could’ve shielded eight-year-old me from watching the video of four Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers—Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno—viciously beat King, but they opted to let me see this previral, viral video as further evidence of the violence of policing. I’d seen this kind of police violence before, but now the world could see what I, my parents, and my community saw on a far too regular basis. This confirmation anchored my growing fear, disdain, and anxiety about police. The uprising that followed the acquittal of these officers was my first encounter with watching the rage of marginalized people set cities on fire in response to police violence. It wouldn’t be the last time. Burned out buildings can be rebuilt though. There’s no justice for those grievously harmed or killed by police.

As my consciousness evolved regarding police violence, I noted how few of the victims discussed in mainstream media were Black women and girls. I also recognized comparatively less community mobilization when police violated Black women and girls in my neighborhood. What I witnessed personally and what I saw on television greatly differed. Black people of all genders were treated as enemy combatants by police officers. The most significant uprising of my childhood pivoted around police assaulting a Black man, but with my own eyes I’d seen cops assault Black sex workers and women living with debilitating drug addiction in my neighborhood. On both a local and a national level, I rarely saw coverage of that or campaigns highlighting police violence against us. This chapter speaks into the void I felt then and adds to a growing number of voices demanding that we grapple with police brutality against Black women and girls right now.

Apart from the response to the nonindictment of the officers who killed twenty-six-year-old Breonna Taylor, cities seemingly only burned in response to direct police violence against some cisgender Black men and boys. The killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and George Floyd compelled folks to take to the streets using the “language of the unheard.”2 Although the founder of @seenblackgirls, @simimoonlught, tweeted, “I see you, black girl. You’ll never be invisible to me. I’ll burn cities down in your name,” back in July 2017, the response to the nonindictment of the cops who killed Breonna was the first time I saw a groundswell of people willing to see the murder of a Black woman as a catalyst for a sustained national uprising. This rallying around a Black woman was unusual given what political theorist Shatema Threadcraft identifies as a “spectacular violent death deficit,” whereby the killings of Black women and girls rarely garner the organizing and mobilizing efforts around Black people killed by police.3 While still not as widespread as the unrest that occurred in the aftermath of some of the more well-known and spectacular incidents of fatal police violence, Breonna’s murder and the nonindictment of the cops responsible for it did bring tens of thousands of people into the streets to proclaim the unjustness of U.S. policing.

Police violence has not only cost billions of dollars in settlements to the loved ones of those harmed or killed by cops. It’s also cost us billions of dollars in rebuilding in the aftermath of these fatal encounters with government-paid and protected employees.4 It’s important to explicitly call out police violence as the root cause of uprisings in the aftermath of yet another Black person killed by police. The destruction of property doesn’t occur if someone’s life hadn’t ended at the hands of violent policing. While it may be easy to dismiss the efficacy of setting cities on fire, policing lit the matches and provided the lighter fluid for those responding to an unchanging pattern. In a criminal punishment system in which property matters more than the lives of Black people, many folks condemn uprisings as unwarranted and unjustifiable responses to police violence. Even those who recognize systemic issues in U.S. policing make false equivalencies between police violence and rebellions against it.5 The refusal to see police violence for what it is and the ripple effects it has on communities resurfaces every time an uprising against fatal police brutality against Black men and boys occurs.

The Ferguson Uprising, which included thousands of people led by residents of Ferguson, Missouri, who erupted in protest in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s killing by Officer Darren Wilson, was my first experience as an adult witnessing a rebellion against antiBlack, racist policing.6 From decrying racism in policing to reports, books, articles, and studies about the criminalization of Black men and boys, I saw a growing abundance of compelling takes on the state of policing in the United States. It was refreshing to see more folks raising questions and concerns about both the origins and state of policing in this nation. What pushed me to say something, however, was how few of these reinvigorated conversations included police violence against Black women and girls. Nevertheless, it finally felt like we approached a moment of semi-collective consciousness around this issue.

In May 2015, the African American Policy Forum and the Center for Intersectionality and Policy Studies led by writer, attorney, and activist Andrea Ritchie and critical legal studies and race theory scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw released the Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality against Black Women report. They not only gave us names of Black women and girls killed by police; they offered a framework for understanding the unique susceptibility of Black women and girls to police brutality and suggestions about how to work with communities to achieve racial justice.7 The report detailed the killing of Black women and girls...

Table of contents

- Imprint

- Subvention

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction. Goddam, Goddam, Goddam

- 1 Say Her Name: Policing Is Violence

- 2 The Caged Bird Sings: The Criminal Punishment System

- 3 Up against the Wind: Intracommunal Violence

- 4 Violability Is a Preexisting Condition: Dying in the Medical Industrial Complex

- 5 Unlivable: The Deadly Consequences of Poverty

- 6 They Say I’m Hopeless

- 7 We Were Not Meant to Survive

- Epilogue: A Letter to Ma’Khia Bryant

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index