eBook - ePub

War Virtually

The Quest to Automate Conflict, Militarize Data, and Predict the Future

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

War Virtually

The Quest to Automate Conflict, Militarize Data, and Predict the Future

About this book

A critical look at how the US military is weaponizing technology and data for new kinds of warfare—and why we must resist.

War Virtually is the story of how scientists, programmers, and engineers are racing to develop data-driven technologies for fighting virtual wars, both at home and abroad. In this landmark book, Roberto J. González gives us a lucid and gripping account of what lies behind the autonomous weapons, robotic systems, predictive modeling software, advanced surveillance programs, and psyops techniques that are transforming the nature of military conflict. González, a cultural anthropologist, takes a critical approach to the techno-utopian view of these advancements and their dubious promise of a less deadly and more efficient warfare.

With clear, accessible prose, this book exposes the high-tech underpinnings of contemporary military operations—and the cultural assumptions they're built on. Chapters cover automated battlefield robotics; social scientists' involvement in experimental defense research; the blurred line between political consulting and propaganda in the internet era; and the military's use of big data to craft new counterinsurgency methods based on predicting conflict. González also lays bare the processes by which the Pentagon and US intelligence agencies have quietly joined forces with Big Tech, raising an alarming prospect: that someday Google, Amazon, and other Silicon Valley firms might merge with some of the world's biggest defense contractors. War Virtually takes an unflinching look at an algorithmic future—where new military technologies threaten democratic governance and human survival.

War Virtually is the story of how scientists, programmers, and engineers are racing to develop data-driven technologies for fighting virtual wars, both at home and abroad. In this landmark book, Roberto J. González gives us a lucid and gripping account of what lies behind the autonomous weapons, robotic systems, predictive modeling software, advanced surveillance programs, and psyops techniques that are transforming the nature of military conflict. González, a cultural anthropologist, takes a critical approach to the techno-utopian view of these advancements and their dubious promise of a less deadly and more efficient warfare.

With clear, accessible prose, this book exposes the high-tech underpinnings of contemporary military operations—and the cultural assumptions they're built on. Chapters cover automated battlefield robotics; social scientists' involvement in experimental defense research; the blurred line between political consulting and propaganda in the internet era; and the military's use of big data to craft new counterinsurgency methods based on predicting conflict. González also lays bare the processes by which the Pentagon and US intelligence agencies have quietly joined forces with Big Tech, raising an alarming prospect: that someday Google, Amazon, and other Silicon Valley firms might merge with some of the world's biggest defense contractors. War Virtually takes an unflinching look at an algorithmic future—where new military technologies threaten democratic governance and human survival.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access War Virtually by Roberto J. González in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

War Virtually

This book is about the pursuit of a dream—a dream that, over time, may turn out to be a nightmare. It’s the story of how a group of scientists and engineers are racing to develop, acquire, and adapt computerized, data-driven technologies and techniques in order to automate war, predict conflict, and regulate human thought and behavior. The advent of artificial intelligence—particularly machine learning—is accelerating the military’s relentless drive toward virtual combat zones and autonomous weapons, in the United States and elsewhere. To the outside world, this sounds like the stuff of fantasy, but from the inside, science fiction appears to be on the verge of becoming science fact. At this stage of history, it’s still not clear whether the outsiders or the insiders will be correct in their interpretations.

Military planners and policymakers are attempting to harness the latest scientific and technical knowledge to prepare for war, virtually. The technological fantasy of virtual warfare is alluring—even seductive—for it suggests that someday we may conduct wars without soldiers, without physical battlegrounds, and maybe even without death.1 Although there is no agreed-upon definition for virtual war, as a starting point we might think of it as a confluence of long-term trends, tools, and techniques: war conducted by robotic systems, some of which are being programmed for ethical decision-making; the emergence of Silicon Valley as a major center for defense and intelligence work; algorithmically driven propaganda campaigns and psychological operations (psyops) developed and deployed through social media platforms; next-generation social science models aimed at discovering what drives human cooperation and social instability; and predictive modeling and simulation programs, including some ostensibly designed to foresee future conflict.2 Although these projects have different historical trajectories, they all have something in common: they’re predicated on the production, availability, or analysis of large amounts of data—big data—a commodity so valuable that some call it “the new oil.”3

In the United States, those undertaking such work are employed in military and intelligence agencies, defense conglomerates and contract firms, university laboratories, and federally funded research centers. The protagonists of the story include computer scientists, mathematicians, and robotics engineers, as well as psychologists, political scientists, anthropologists, and other social scientists. At its core, this book is about how these men and women are attempting to engineer a more predictable, manageable world—not just by means of electronic circuitry and computer code, but also by means of behavioral and social engineering—that is, human engineering. Under certain conditions, cultural and behavioral information can become a weapon, what in military terms is called a force multiplier—a way of more effectively exerting control over people and populations.

Given the breathtaking scope of the proposed technologies and their potential power, it’s easy to overlook their limitations and risks, since so many of them are still in the realm of make-believe. It’s even easier to overlook the serious ethical and moral dilemmas posed by autonomous weapon systems, predictive modeling software, militarized data, and algorithmically driven psyop campaigns—particularly at a time when some observers are warning of an “AI [artifical intelligence] arms race” between the United States and rival powers.4

The rush to create computational systems for virtual warfare reveals a fatal flaw that’s been with Homo sapiens as long as civilization itself: hubris, that persistent and terrible human tendency to embrace blind ambition and arrogant self-confidence. The ancient Greeks understood this weakness, and learned about its perils through myths such as the tragedy of Icarus, a young man so enthralled with the power of human invention that he forgot about its limits. But instead of tragedy, our myth-making machinery produces technological celebrities like Tony Stark, Iron Man’s brash, brilliant alter ego. There’s little room for hubris—much less ethical ambiguity—in the Manichean fantasy worlds of Hollywood superheroes and American politics. But it’s important to remember how, in a heavily militarized society like our own, overfunded technology projects and reckless overconfidence can quickly turn to disaster.

UPGRADE

The latest generation of military tools is a continuation of long-standing trends toward high-tech warfare. For example, US scientists have experienced changing patterns of military influence over their work during the course of at least a century. In the early 1960s, as the United States was about to escalate its war in Vietnam, a well-known physicist famously told Defense Secretary Robert McNamara that “while World War I might have been considered the chemists’ war, and World War II was considered the physicists’ war, World War III . . . might well have to be considered the social scientists’ war.”5 By that time, military and intelligence agencies were integrating knowledge from psychology, economics, and anthropology into their tactical missions, provoking controversy and criticism from social scientists concerned about the lethal application of their work.6

But what’s happening today is broader in scope than anything the military-industrial complex has created before. If you think of the earlier phases of high-tech conflict as versions 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0, then you might say that in the twenty-first century, a major upgrade is under way: chemists, physicists, and social scientists are now working together with roboticists and computer scientists to create tools for conducting data-driven warfare. The advent of War 4.0 is upon us, sparked by the so-called Revolution in Military Affairs—the idea that advanced computing, informatics, precision strike missiles, and other new technologies are the answer to all of America’s security problems. In recent years, observers have warned of a drift toward “future war,” the rise of “genius weapons,” and “T-minus AI.”7

Like most updates, the latest version of warfare is built upon what came before. More than a half-century ago, the US military launched an advanced electronic warfare campaign targeting enemy convoys traveling across the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of roads linking North and South Vietnam. For the Vietcong, the route was a vital lifeline for transporting equipment, weapons, and soldiers. The US military program, dubbed Operation Igloo White, used computers and communication systems to compile data collected by thousands of widely dispersed electronic devices such as microphones, seismic monitors, magnetic sensors, and vehicle ignition detectors. Despite high hopes and a gargantuan price tag, the program was not nearly as effective as its architects had hoped.8

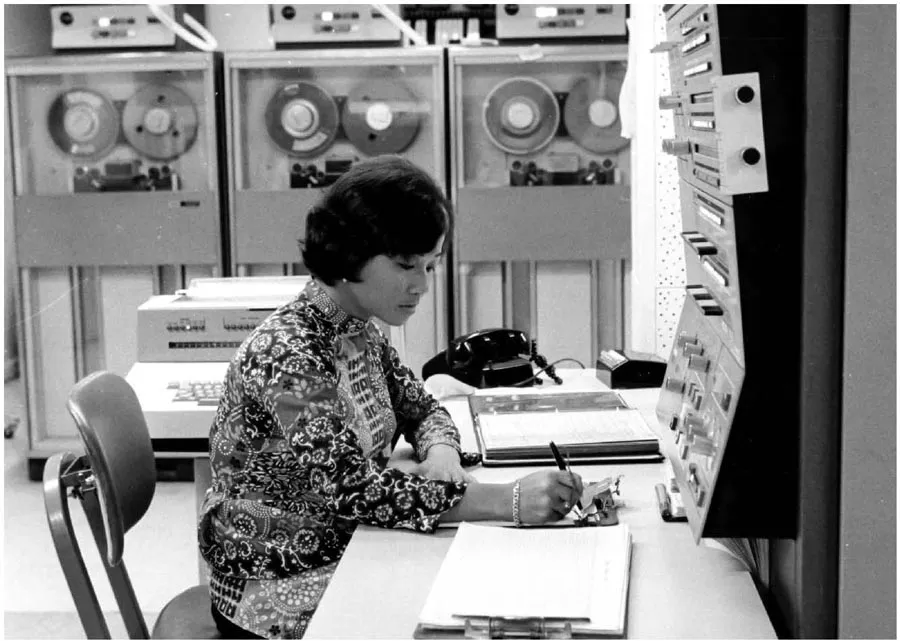

Such efforts weren’t limited to the collection of hard data—sometimes, they were based on “soft” social science data. A case in point: the Phoenix Program, a brutal counterinsurgency initiative launched by the CIA and the Defense Department in 1968. At about the same time that Operation Igloo White was under way, military officials and intelligence agents were using IBM 1401 mainframe computers to compile ethnographic and demographic information collected by US civil affairs officers. Eventually, they created a database of suspected Vietcong supporters and communists. American advisors, mercenary fighters, and South Vietnamese soldiers then used the computerized blacklist—called the Vietcong Infrastructure Information System—to methodically assassinate more than twenty-five thousand people, mostly civilians, under the aegis of the Phoenix Program. For its users, the computer program magically transformed what would otherwise appear to be a subjective, arbitrary, bloody assassination campaign into a seemingly rational, objective, and antiseptic process of social control.9

War 4.0 differs from earlier forms of automated conflict and computerized weapon systems. While it’s true that US military personnel used computers as early as 1946, when they programmed ENIAC (the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) to develop better ballistic trajectory charts and hydrogen bombs, today military and intelligence agencies and firms are using not only advanced computational hardware and software, but also vast amounts of data—and from infinitely more sources. The term big data, ambiguous as it is, hints at the scale of change. Apart from the expansion of electronic sensors ranging from high-resolution satellites and drones to closed-circuit TV cameras, billions of people around the world leave enormous amounts of digital residue behind when using the internet, social media, cell phones, personal fitness trackers, and virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa.10 Both actual (face-to-face) and virtual (face-to-screen) interactions are subject to closer surveillance than ever before. Military and intelligence agencies don’t always have easy access to this data, but many of the corporations that control such information—such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—have forged close relationships with the Pentagon and the US intelligence community.

Figure 1. At the height of the US war in Vietnam, American government agencies and the military used IBM mainframe computers for the Phoenix Program. Photo courtesy of Michigan State University Archives.

Another difference is that the technologies often rely on algorithms to construct behavioral models for anticipating or even predicting human behavior, in virtual and actual realms. Algorithms provide the means by which large amounts of raw data about our virtual lives can be processed and reassembled as probable outcomes, political preferences, propaganda, or products. If you’ve ever used Facebook, Instagram, Amazon, Netflix, or Google, you probably have an intuitive sense of how the algorithms work. Unless you’re willing and able to opt out by changing your privacy settings—which is typically a cumbersome, confusing, time-consuming process—companies constantly track your internet searches, online purchases, and webpage visits, then feed the data into mathematical formulas. Those formulas, or algorithms, use that data to make calculations, essentially educated guesses about what you might like, and then “recommend” things to you—clothes, shoes, movies, appliances, political candidates, and much more.11 Algorithms are what fill your news feeds with articles based on your previously monitored online reading or internet browsing habits, and Big Tech firms have built an industry on them by using your data to help their clients target you for online ads. These techniques have helped Facebook, Google, and Amazon dominate the world of digital advertising, which now far eclipses print, TV, and radio ads.12 When people are transformed into data points, and human relationships become mere networks, the commodification of personal information is all but inevitable without meaningful privacy regulation. What this means in practical terms is that all of us risk having our digital lives become part of the military-industrial economy.

From the perspective of a data scientist, handheld internet-ready digital devices have transfigured billions of people worldwide into atomized data production machines, feeding information into hundreds, if not thousands, of algorithms on a daily basis. The militarization of this data is now a routine part of the process, as suggested by recent reports detailing the Defense Intelligence Agency’s use of commercially available geolocation data collected from cell phones.13 Military and intelligence agencies can use such data not only for surveillance, but also to reconstruct social networks and even to lethally target individual people. A dramatic case occurred in September 2011, when, in a joint drone operation authorized by the Obama administration, CIA and US military personnel assassinated Anwar al-Awlaki—an ardent US-born Muslim cleric—in Yemen. Those who organized the drone strike targeted Awlaki based on the location of his cell phone, which was monitored by the National Security Agency as part of a surveillance program. Two weeks later, a CIA drone attack using the same kind of data killed another US citizen: Awlaki’s sixteen-year-old son, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki.14

Although Awlaki was intentionally assassinated by US forces, other Americans—and many thousands of civilians in Afghanistan and other parts of Central Asia and the Middle East—have been inadvertently killed by drones.15 These cases foreshadow a major flaw in the latest iteration of automated war: the imprecision of the technologies, and the great margins of error that accompany even the most sophisticated new weapon systems. In their most advanced form, the computerized tools make use of artificial intelligence, such as iterative machine learning techniques. Although proponents argue that the weapons perform at levels comparable or even superior to humans, they rarely provide conclusive evidence to support their claims. Yet the march to adopt these machines continues apace. The Pentagon’s quest to develop AI for military applications has led to the creation of an Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team, also known as Project Maven. Among its first objectives was to analyze thousands of hours of video footage from drones to produce “actionable intelligence” that might be used to locate ISI...

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Terms and Abbreviations

- 1. War Virtually

- 2. Requiem for a Robot

- 3. Pentagon West

- 4. The Dark Arts

- 5. Juggernaut

- 6. Precogs, Inc.

- 7. Postdata

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Sub-rosa Research

- Notes

- References

- Index