![]()

Part One

Edinburgh Society

![]()

1

The Burgh Community: Pressures and Responses

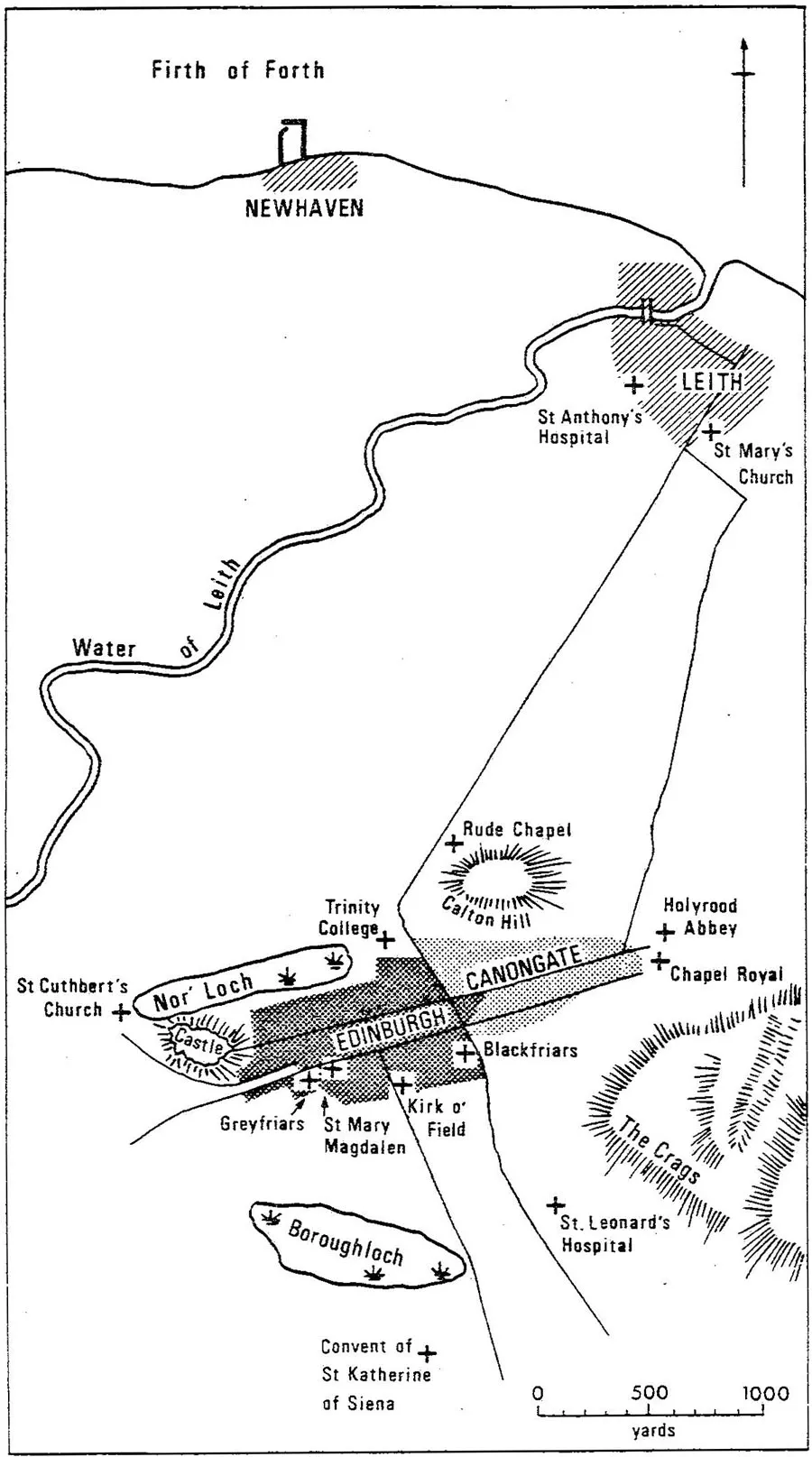

EDINBURGH was by the middle of the sixteenth century a city which was threatening to burst its narrow seams. The town ran for a thousand yards from west to east along the spine of a ridge gently sloping down from the Castle to the great port, or gate, at the Netherbow, reconstructed in the course of the civil wars in 1571. On each side of the High Street, which was first paved in 1532, the ridge sloped steeply away, covered by a series of narrow closes and close-packed timber-fronted houses. A natural boundary was formed to the north by the Nor’ Loch, which was increasingly becoming an open sewer, while to the south the town had already spilled over the old city wall built in the 1420s and beyond what had in past times been the wealthier, more spacious suburb of the Cowgate up to the line of a new wall. This was the so-called Flodden wall which was still not completed in 1560. Even so, the burgh was hardly four hundred yards wide from north to south and the total area within its walls comprised only one hundred and forty acres. It was largely within these limited bounds that there was contained the bulk of a population which was large enough for most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for Edinburgh to lay claim to being one of the two largest cities in the British Isles outside London.

There is a paradox here. The tendency has almost always been for historians, and particularly recent Scottish historians, to stress the smallness and intimacy of all the Scottish burgh communities in this period, and Edinburgh among them. It is true that a number of contemporary observers did compare Edinburgh’s size unfavourably: Froissart at the end of the fourteenth century thought the town had fewer than four hundred houses; a French visitor in the early 1550s likened Edinburgh in size to the small provincial city of Pontoise. Yet others pointed out the remarkable density of the burgh’s population; the due de Rohan in 1600 and David Buchanan half a century later claimed that there was no other town of its size so populous. Certainly by the standards of recent historians of the early modern town Edinburgh’s population was large; it rivalled that of Norwich, the largest city in England outside London, and was akin to a city the size of Bremen.1

Precisely how large it was is difficult to quantify exactly but Edinburgh’s population within the walls was certainly very close to twelve thousand in 1560. The figure, as we shall see, would rise to somewhere between fifteen and eighteen thousand if greater Edinburgh was taken account of, by including the separate jurisdiction of the burgh of the Canongate and other nearby baronies just outside the walls, like Bristo. The significant point is that Edinburgh’s population more than doubled in the century after 1540. The bulk of that increase probably came after the last serious outbreak of the plague in 1584. Because the burgh was engaged until the 1630s in a long series of jurisdictional disputes with a number of its near-neighbours, which prevented significant growth into the surrounding hinterland, the only way to accommodate this dramatic rise in population was to expand not outwards but upwards. The soaring tenements in the Lawnmarket at the head of the High Street of four, five and six storeys, and eventually of fourteen and more, belong to the period after 1580. Edinburgh was fast in process of becoming a prosperous, thriving and bustling metropolis while yet retaining many of the restrictive habits and most of the dimensions of the old medieval burgh. The town’s walls serve as a reminder that the reformation took place within the context of the closeted thinking of a medieval burgh.

This was a society which, nevertheless, continued to cherish the old idea of itself as a small and close-knit community. It was an idea, of course, which had a religious dimension to it as well as a social or economic one. The burgh was seen as a corpus christianum; its council had responsibilities towards the spiritual as well as the secular welfare of its inhabitants. Most of the organisations within burgh society had the same double aspect to them. The craft guilds were religious societies as well as privileged groups monopolising their skills. The reformation did little or nothing to alter either of these aspects; the craft altars in St. Giles’ disappeared but not the religious ethos of the guild. Edinburgh society throughout the sixteenth century and beyond remained paternalistic and deeply conservative.

At the same time, however, the religious changes which took place did so within the context of developments which were increasingly putting many of the old assumptions about the organisation of burgh life under strain. The town’s swelling population made some of the arrangements laid down in the Statuta Gildae of the twelfth century increasingly impractical. The old practice of the town, or at least of the free burgesses in it, meeting together in an annual head court had probably been abandoned for the better part of a century. The council’s fears of craft insurrections after the riots of 1560 and 1561 resulted in the curtailing of the old right of an offender to appear before it accompanied by all the brethren of his craft.2 The increasing sophistication and prosperity of certain crafts had led to large numbers of leading craftsmen being admitted to the prestigious and formerly exclusive merchant guildry, and as a result the line between merchant and craftsman was having to be redrawn in a process completed by the revision of the town’s constitution in the decreet-arbitral of 1583. Price inflation, kindled by the harvest failures of the late 1560s, set alight by the economic blockade of the town during the civil wars and kept smouldering by Morton’s debasement of the coinage in the 1570s, induced the council to cling desperately to the traditional but increasingly ineffectual practice of fixing food prices. In addition, a series of externally imposed political crises, ranging from the invasion of the town on three separate occasions by the Lords of the Congregation in 1559 and 1560 to the traumatic siege of the burgh in the wars of the early 1570s, helped to intensify the natural conservatism of the burgh establishment.

Map 1

Yet while the town expanded its population and became increasingly diverse in character, as it flourished in its roles as a centre for the royal court and the law with the development of a central court for civil justice in the fifteenth century, it clung to the old but necessary myth of seeing itself as a corporate society. The town’s existing institutions were stretched to meet the growing pressures on them just as its buildings were stretched to accommodate a growing population. The changes which took place were cosmetic rather than fundamental and this applied as much to the celebrated decreet-arbitral, often seen as the hallmark of a hard-won democracy for the crafts, as to anything else. Power remained in much the same hands in the 1580s as it had in the 1540s. There was just one real difference — there was more of it. Edinburgh is a good illustration of the cardinal principle that the larger a town was or became in the sixteenth century, the more oligarchic its government was likely to be.3

If Edinburgh’s physical smallness was one of its most surprising features in this period, the other was the fact that it did not control a contado around itself. Its port, the vital artery for its trade both with the east coast and overseas, with France, Flanders and the Baltic, lay two miles away at Leith. The burgh’s jurisdiction over its own port was complicated, uncertain and acrimonious. It formed the basis of what John Knox in his History called the ‘auld hatrent’ between Leith and Edinburgh and brought the burgh into a series of disputes with a number of influential figures who held rival interests or saw an opportunity for profit. This increasingly expensive and worrying legal tangle was not firmly resolved to Edinburgh’s satisfaction until 1639.4 Predictably, the burgh also had its difficulties with the Canongate, a separate ecclesiastical burgh of regality which stretched eastwards from the port at the Netherbow down to the abbey and royal palace at Holyrood. These lasted until Edinburgh finally gained the superiority in 1636. With its more spacious lay-out and relaxed atmosphere the Canongate increasingly became a residential suburb for courtiers and members of the central administration. There were continual minor disputes over the rights of the Canongate’s skilled craftsmen to sell their wares on the High Street. Edinburgh took the Canongate to court in 1573 and, to its dismay, lost.5 The Canongate also acted as an annoying safe haven, tantalisingly just outside Edinburgh’s jurisdiction, for burgesses seeking to evade their civic duties and also for catholics. There were further minor irritations caused by clusters of craftsmen and brewers who were not burgesses living outside the West Port and two of the other gates on the south side until the town acquired the superiority of Portsburgh by purchase in 1648.6 All these nagging jurisdictional worries helped to keep the burgh an inward-looking society, clinging to the letter of the law wherever its economic privileges and monopolies were involved.

A third feature, but one much more difficult to assess in its effect, was the large number of noble houses within half a day’s ride of the burgh. Two contemporary observers claimed that there were as many as a hundred.7 A number of local lairds, like the Napiers of Merchiston, were burgesses but their influence in the political affairs of Edinburgh was surprisingly small. A number did sit on the town council from time to time but there were no ruling cliques in the sixteenth century like the Menzies family in Aberdeen, which virtually monopolised the office of provost until the 1590s.8 The progress of the Reformation probably had a good deal to do with the influence of local lairds in many burghs but far less so in Edinburgh where the stakes were higher and the players more formidable.9 The key factor in Edinburgh politics was often the intervention of the crown itself or of a faction within the court. The two most powerful outside influences came from the two rival noble houses of Morton at Dalkeith and the staunchly catholic Setons.10 Crown or court managed to impose a nominee as provost of the burgh for fully twenty-five years after 1553 but interference with the lower levels of the ruling establishment was much rarer, occurring only a handful of times in the period. Each of these occasions, however, is noteworthy — Mary of Guise’s imposition of bailies on the town in 1559, countered by the Congregation’s wholesale replacement of the council two weeks later; the three interventions by her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, in burgh politics between 1561 and 1566; the forcing into exile of the council by the queen’s lords in 1571; and the purge of radical supporters of the short-lived Ruthven regime forced upon the council by James Stewart, earl of Arran, in 1583. Between these low-points the council had to put up with a fairly consistent barrage of threats, bullying and noble violence on its streets. External threats and externally imposed crises were things the burgh simply had to live with in the middle quarters of the sixteenth century.

It would be easy enough to go one stage further in describing reformation Edinburgh by sketching a picture of a city divided within itself, of merchant against craftsman, catholic against protestant, magistrates against unruly mob. All of these patterns did occur but only sporadically and they seldom linked up, one with the other. Burgh life had to go on and the town was too small in its size and its thinking to admit permanent divisions within it, whether of an economic or a religious complexion. It was not the internal tensions within burgh society which set the tone of Edinburgh’s reformation. There is little trace in the 1550’s of the pattern which had been common in most of the German cities of protestant ideas being fostered by the craft guilds, partly as a policital lever against the town establishment.11 Certain of the crafts remained catholic strongholds for most of the 1560s but the tension which existed between merchants and crafts did not take on the mirror image of a struggle by catholic craftsmen against a protestant-dominated merchant oligarchy. The key to understanding the burgh’s complicated and shifting reactions during the reformation period lies rather in coming to grips with the recurrent but unpredictable pressures put upon it from outside. The court and the labyrinth of factions within it — and, at times of crisis, outside it — together with the open door of the resident English agent, Thomas Randolph, a classic example of an ambassador of ‘ill-will’,1...