![]()

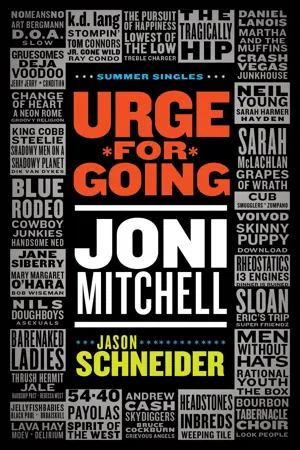

URGE FOR GOING

JONI MITCHELL

A DARKNESS HUNG over the summers in those days. No one talked about it directly, but the fear was obvious in parents’ faces when they let their children out to play in the fields of tall, yellow grass in the morning. The boys would organize primitive baseball games, while the girls skipped rope. And when they all came home at night for supper, their every movement would be keenly scrutinized for traces of fever or twinges of pain. If anything was detected, the mothers would calmly put the children to bed, and then stay up all night silently praying that when dawn came they would hear the familiar din of small feet on the wood-plank floors, and voices expressing eagerness to spend another day outside with their friends.

Mothers who were not so lucky would awake to silence, or worse, to the screams of a child suddenly unable to move. Polio was a curse that by the early fifties could not be tolerated much longer. In Canada, as in most countries around the world, the disease was in the process of scarring its third generation, and the only treatment was painful therapy or confinement in an iron lung. Yet, for the children who survived the physical and psychological trauma of the disease, it was a rite of passage that no one else could begin to understand. For them, something fundamental had changed; those old enough to comprehend their mortality discovered new paths that were not contingent on physical abilities, while those too young to know how close they had come to dying eventually noticed that people looked at them differently. They were somehow stronger, they were survivors, and were duly shown respect.

In 1951, a five-year-old boy caught the disease on the eve of his return to school in the tiny village of Omemee, Ontario, an hour’s drive northwest of Toronto. The proximity to the big city saved his life, although he would require several months of rehabilitation to learn how to walk again. Two years later, a nine-year- old girl from the town of North Battleford, Saskatchewan, caught it, and was similarly spared any major damage after being brought to the closest modern hospital, in Saskatoon. When they met for the first time, in Winnipeg in 1965 — the boy was visiting for Christmas and the girl was passing through, performing her folk songs — something deeply familiar struck each of them. It was partially the music she played, music unlike anything the rock and roll–crazed boy had heard before, but mostly it was something he felt within himself: the mark that the pain had imprinted on her fearless personality. She picked up on his internal marks right away, too, and, after finding an opportunity to talk, they spoke to each other in a way only they could fully understand. The mark left them with a belief that a part of them was indestructible, and merely knowing that there were other people in the world who possessed such a quality allowed them to share something greater than mere romance (she was already married, anyway). They had seen up close what lay ahead for everyone — what must eventually consume us all — and they had learned from it that there was much to be accomplished before they ultimately landed back in some anonymous hospital bed, alone, in spite of everything. They had been given their second chances long before others had realized that life had so much more to offer. The young man thought of this as he listened to her angelic voice and pictured her in the same leg braces he had been forced to wear. Her voice told him it was now time to put everything else that had ever bound him behind him for good.

Roberta Joan Anderson was born on November 7, 1943, in Fort MacLeod, Alberta, the only child of a Royal Canadian Air Force lieutenant, Bill Anderson, and Myrtle McKee, a Regina native he had met and married in a whirlwind while on leave the previous year. Fort MacLeod had the nearest hospital to his base, and the family remained there after Joan’s birth until the end of the war, when they settled in Maidstone, Saskatchewan, where Bill got a job managing the town grocery store. By the time Joan began school, her father had been transferred to his store chain’s outlet in North Battleford, and she assumed the image of a tomboy. Simultaneously, she exhibited a talent for drawing, along with an interest in several of her friends’ musical pursuits. Following her recovery from polio, Joan fully embraced her artistic side, something that was of great benefit when she entered high school in Saskatoon, her father’s next destination. A self-described bad student, she wrote poetry and a column for the school paper, and painted backdrops for school drama productions to compensate for her grades.

She also utilized her artistic talent to paint portraits of her teachers, and as a gift for one of these, Joni — the new spelling inspired by an art teacher, Henry Bonli — received, in return, a selection of Miles Davis albums. An interest in jazz replaced her natural teenage infatuation with rock and roll from then on, and it would remain her primary musical love even after the folk revival swept her friends away as their high school days wound down. There was no avoiding folk music in 1962, though, and during summer excursions with friends to remote northern lakes that year, Joni’s natural desire to join in led her to pick up a guitar and chime in with a few simple chords, or simply sing along with the choruses. “I had a lot of attention as a youngster,” she said. “I was popular, a dancer in high school. I didn’t have anything to prove. At the heart of me, I’m really a good-time Charley.”

The search for fun carried on through her final school year, as most kids had by then discovered the Louis Riel, Saskatoon’s own bona fide beatnik coffee house. It was there, on Halloween, that Joni made her first public performance as a singer, earning a few dollars in the process, and enough positive reaction to come back and sing a few more songs the following week. Yet, for all the misgivings she may have still harboured about the folk movement, the following summer she was faced with the need to earn enough money to cover her enrolment at the Alberta College of Art and took a job waitressing at the Louis Riel, while supplementing her income with work as a model for several Saskatoon dress shops.

As she endured serving coffee against the backdrop of a steady stream of touring folk performers, Joni eventually could not resist getting on stage again herself. After purchasing a cheap baritone ukulele, she regularly participated in the café’s weekly hootenanny, and was soon caught up in the ideas of the folk revival, ideas she realized were more applicable to her circumstances than the more distant, urban world of jazz. She showed up everywhere with her ukulele that summer, and took every opportunity to play her expanding repertoire of popular standards. At one of these informal gatherings, Joni captivated some employees of a television station in the northern Saskatchewan city of Prince Albert. Afterward, they asked if she could do a one-off half-hour program in place of the station’s normal Saturday night show dedicated to moose hunting (the season for which didn’t start until the fall). Joni immediately agreed, and the August 1963 broadcast brought her first taste of fame, just before she set out for Calgary and her post-secondary education.

The task of studying art came easily, although Joni was unable to completely adjust to the college environment. As she explained, “I found out that I was an honour student at art school for the same reason that I was a bad student [in general] — because...