![]()

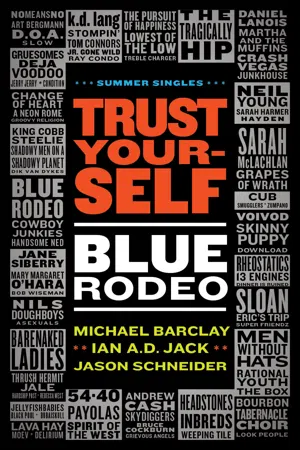

Trust Yourself

Blue Rodeo

“They’re great songwriters with undeniable songs. In 1988, here was a band that’s unpretentious, doesn’t dress up, and probably played with three lights over their heads. In Canadian music, that was a turning point back to what’s real, what has longevity — what’s going to make people think in five years that these songs still have relevance to their everyday life.”

COLIN CRIPPS (CRASH VEGAS, KATHLEEN EDWARDS)

THE 1988 JUNO Awards marked a watershed for Blue Rodeo. The notoriously conservative and industry-driven institution bestowed the new band with honours for Group of the Year, as well as single and video awards for the ballad “Try.” Three years earlier, “Try” was one of four songs on a demo tape that was rejected by the same A&R rep who would later sign them; the tape featured two other songs that would be singles from Blue Rodeo’s multi-platinum 1987 debut Outskirts. Blue Rodeo had assumed that their hybrid of psychedelic-tinged country rock would never break through to the mainstream. On this night, they had received the first of many affirmations that would grant their career a longevity that previously didn’t seem feasible in the Canadian music industry.

“From the outset we knew that we were at the beginning of something different in Canada, which was the beginning of a real domestic scene,” says Jim Cuddy. “That domestic scene was not defined by how well that music travelled, but only by how much it represented people within the confines of the country. We understood that at the ’88 Junos. All the bands that played that night all had double platinum records and they were all Canadian. It was apparent that a change in Canadian music had happened.”

That year’s awards ceremony would name Robbie Robertson Male Vocalist of the Year and his debut solo work the Album of the Year; his alma mater the Band were also being inducted into the Juno Hall of Fame. The Band was a frequent point of comparison when critics tried to describe Outskirts, and although Blue Rodeo’s creative core of Greg Keelor and Jim Cuddy dominated the group’s output, Blue Rodeo boasted a group of individual characters not unlike the Band: keyboardist Bob Wiseman’s wildly inventive work sounded like a hallucinogenic Garth Hudson; Bazil Donovan’s melodic and soulful bass work recalled that of Rick Danko’s; and versatile drummer Cleave Anderson anchored the band with a deceptively simple style, much like that of Levon Helm.

The Juno organizers had decided it would be a great idea if the Band and Blue Rodeo performed together on the televised program. Jim Cuddy recalls the first meeting between the underdog newcomers and the first Canadian superstar band. “We got set up in the room at the CBC for rehearsal, and in walked Robbie, Rick Danko, and some guy who looked like a piano tuner but was actually Garth Hudson,” says Cuddy. “The first thing Robbie said was, ‘There’s too many people here. We only need a bass player and a drummer.’ The guy who put it all together was Rick Danko. He was the nicest, friendliest guy, who was so open to anything. He’d say, ‘Yeah, two bass players!’ He was completely into it and broke the ice, because there was a lot of ice formed by that reception. We had lots of meetings with Rick over the years. He was really a gregarious, open soul you liked the moment you met.”

During the remainder of their career, Blue Rodeo would have more in common with the amiable Danko than the aloof Robertson. Blue Rodeo was the hard-working, low-key Canadian band that created great art in pop songs and played every small town in Canada in the process. That Juno night in 1988 after their performance with the Band, the normally cynical Greg Keelor was caught gushing on MuchMusic: “Robbie played my guitar!” Cuddy, always keeping his creative partner in check, turned to the camera and said, “Isn’t rock and roll pathetic?”

Greg Keelor was raised on a steady diet of music and hockey in the “suburban paradise” of Mount Royal, Montreal in the late ’60s, where two of his hockey pals were John and Michael Timmins, later of the Cowboy Junkies. Keelor finished high school in Toronto, where he met Jim Cuddy at North Toronto Collegiate in 1971. “We weren’t the greatest of friends in high school, but we hung out in the same crowd,” says Keelor. Neither one of them played music in public. After graduation, Cuddy and two friends had renovated a school bus as a mobile home and planned to discover Western Canada. When one of the friends dropped out, Keelor took the seat. The bus broke down in Moosomin, Saskatchewan, and the high school buddies headed to Alberta to earn money and wait for its repair; Keelor went to Lake Louise, and Cuddy went to Banff, where he met another Ontarian named Robin Masyk, who would later move to Toronto and call himself Handsome Ned.

Independently, both Keelor and Cuddy nurtured their musical muses in the Rockies. Cuddy started playing guitar in coffeehouses, while Keelor learned how to play guitar from songbooks of Gordon Lightfoot and the Everly Brothers. Cuddy also shared an affinity for Lightfoot; the first song he learned how to play, at age 10, was the Canadian folk legend’s “That’s What You Get For Loving Me.” Cuddy had been passionate about music ever since, but wasn’t sure it would be a large part of his future. “A lot of the struggle for me when I was younger was accepting that I wanted to define myself as an artist and a musician,” he says. “There were no artists in my family. Music was a hobby, and that way of life was temporary. Committing yourself to being an artist is in one way a vow of poverty. So until I found some reasonable job that I could do while still doing music, I was very conflicted about doing it.”

In 1975, Cuddy returned to Ontario to attend Queen’s University in Kingston, and when he landed in Toronto in 1978, he and Keelor formed the Hi-Fi’s with bassist Malcolm Schell and drummer Jimmy Sublett. Michael Timmins recalls, “They were a power pop band, very influenced by the Beatles and the Jam. They were a really good band, really exciting — very high energy.”

Keelor says, “What we sounded like and who I think we sounded like are two totally different things. But in terms of our major influence, it was the Clash. They were the band who survived the whole punk thing; they were the band with the integrity and the sound. Locally, it would be bands like the Secrets or the Demics or the Mods.”

For Keelor, the goals of the Hi-Fi’s were modest, starting with an independent single, “I Don’t Know Why (You Love Me)” on their manager’s Showtime label. “We just wanted to make a record and hang out and live the musician lifestyle,” he says. “We did a weekend gig in Kitchener at this big rock place. Goddo had been there on the weekend and filled the place. Then we came in to play Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, and had 40 people in this bar that held 1,200 people. Our manager came to one of those shows; his line was, ‘The phones aren’t ringing off the wall for you guys.’ ”

The band was approached by Ready Records, an independent Toronto label that was home to Blue Peter, Santers and the Spoons, although at that time the Hi-Fi’s were experiencing hometown bringdown. “By ’81 the scene — punk, post-punk, new wave — was evaporating, or at least as far as we could see,” says Keelor. “There was no place to play, and it didn’t seem that record companies were going to sign bands like that.”

The Hi-Fi’s disbanded after the Ready deal fell through, and Keelor and Cuddy packed up for New York City. Cuddy’s brother lived near Washington Square, and his girlfriend and future wife, Rena Polley, had been accepted to theatre school there. “Going to New York was such a conscious choice of getting out of Toronto and getting away from personal history,” says Cuddy. “Like many other places in the world, New York is a place where there’s so much encouragement to turn your inclination into expression — whether you’re an actor, painter, sculptor, street artist, anything.”

While down there, they hooked up with Michael Timmins and Alan Anton, who had also moved there with Hunger Project. “They were over in Alphabet Town, because the rent was so cheap. You could get a big apartment in those days for three hundred bucks,” Keelor recalls. “[New York] was very intimidating then. It felt like a war zone; it looked like Beirut. You’d look down the road in the winter, and on every block there’d be a barrel with a fire burning in it and street people standing around collecting scraps of wood to burn to keep warm. The first day [Timmins and Anton] went out, they hadn’t put bars up on the windows; they locked it up and they came back and the blaster [radio] had been stolen, so they realized they had to make their place a little more secure. They cut a hole in the floor which led to this little bunker that we both rehearsed in.”

“We learned a lot of musical stuff from [Hunger Project],” says Cuddy, “because they used to jam a lot and we didn’t. We were pretty pop-oriented at that point. When we would jam with Hunger Project, we’d do these long, mesmerizing jams and learn things about that. New York was the most extreme part of our learning curve. The good part of it was that we didn’t know what kind of band we were. It was a pretty confused musical scene at that point too, between 1981 and ’84, unless you were into the New Romantic stuff, which we certainly weren’t. You could do rock, ska, pop, anything. We weren’t very good at any of them, but we learned a lot.”

Keelor and Cuddy dubbed their new project Fly to France, which Cuddy admits “was a truly stupid name,” as was its successor, Red Yellow Blue. The revolving line-up was rounded out by musicians they found through a Village Voice ad; Keelor and Cud...