![]()

1

Domestic inspectors: The First Gulf War and the militarization of the home

We are, we seem to be, on the edge of war. At the threshold. A line has been drawn. Literally, a deadline. In crossing that line, we go to war. We go outside. We leave the homeland and do battle on the outside. But there are always lines in the interior, within the apparently safe confines of the house. Even before we step outside, we are engaged in battle. As we all know but rarely publicize, the house is a scene of conflict. The domestic has always been at war.1

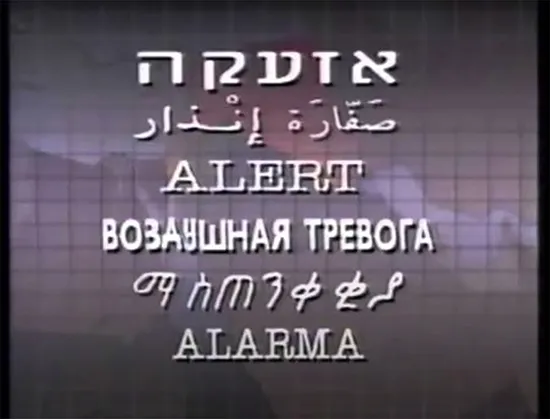

Following several weeks of uncertainty and a few hours after the US air force commenced an intensive airstrike on Bagdad, in 17 January 1991, the Iraqi military fired an Al Hussein scud missile in Israel’s direction. Scrambling to report on the long-dreaded attack, the live public television broadcast aired one slide with the word alert flickering in six languages to signal to civilians that the time has come to take cover (Figure 2). But despite the alarming sound of sirens, one anonymous civilian intuitively grabbed his personal camera and directed it to the dark skies above. The grainy footage recorded that night depicts a small flare crossing a dark screen, until hitting the ground with a white flash.

Figure 2 A frame from the live television broadcast during the bombardment, 1991 (Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVFV6RTvP28s).

I found this video buried deep in the IDF archives, between dozens of trivial papers from the early 1990s that document exchanges between military officers. According to the archive’s search history, I was the first to view the tape since it was filed in the archive, almost three decades ago. Watching the tape for the first time on the monitor in the archive, it seemed odd that this video would be of any significance to the IDF. Nevertheless, the 30-second clip captured what state-run television failed to record: the first missile fired in Israel’s direction by the Iraqi army during the 1991 Gulf War. The video was later obtained by the military spokesperson and broadcast on television for all to see.

The details in the frame are barely legible; instead, the singular perspective of the amateur filmmaker is the communicated massage. The audio-visual document registers something that does not appear in the frame. That is, it documents practices of domestic filmmaking re-appropriated for the first time, to document a national emergency. The sharp movements of the camera and the agitated zoom-in on the incoming missile are the seismograph registering the rapid activation of the individual user of media as part of the Israeli security apparatus.

Indeed, more than mere unintelligible noise, the homemade video marks the intersection of two distinct transformations that took shape in the early 1990s. On the one hand, the availability of personal cameras and the rapidly growing market of camcorders for domestic use. Analog video format for camcorders was introduced by Sony in 1989 and found eager consumers. On the other hand, the escalating sense of uncertainty that permeated homes in Israel due to threats made by Iraq. Together, the two opened a window of opportunity for the Israeli state to incorporate new sources of visual media into their public relations apparatus that absorbed the private use of domestic cameras.

Looking at the circumstances that led to the filming of this homemade video and others like it, in this chapter I suggest that the fusion of available technologies and collective national paranoia enabled the rapid militarization of the everyday, and the enlisting of civilians as amateur filmmakers that do not merely film their own routines but supplement the state’s vision. This chimera that merges available technologies and collective paranoia surfaced in the First Gulf War and paved the way for the state to co-opt the personal use of media.

Only some months before the amateur video was filmed, the Israeli government had declared a state of emergency. Saddam Hussein, in an attempt to deter the United States from mobilizing a military intervention into Baghdad, threatened to target Israeli cities with missiles that potentially carry nuclear, chemical and biological warheads. Arming Iraqi soldiers to engage in war, Hussein had warned in December of 1990 that if the Iraqi people ‘must suffer the first blow, whether at the front or here in Baghdad, and whether or not Israel participates directly in the aggression, they will suffer the second blow in Tel Aviv’.2 The United States perceived Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait as an attempt to challenge the regional order and to assert hegemony over the Middle East. Of course, there was also the incentive to protect their financial interests by intervening in the local geopolitics and standing with Saudi Arabia to secure access to oil. Considering its longstanding alliance with the United States and its long-standing occupation of Palestine territories, Israel became a target by proxy.

Jewish-Israeli citizens in Israel, usually well-shielded from the violent clashes in Gaza and the West Bank, were now, if only momentarily, exposed to direct missile strikes and to the invisible threat of nerve gas. Catching Israel at the height of a bloody intifada in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the missile attack was not only a threat to Israel’s otherwise well-protected civil sphere (‘Homefront’), but was also perceived as a public relations opportunity that, if presented correctly, could potentially resuscitate the public image of Israel as a small state under the looming threat of annihilation. This was a contrived fantasy designed by Israel from its inception to justify the occupation of Palestinian territories. By winning over the urge to retaliate, the Israeli Prime Minister Itzhak Shamir believed that the crisis might well be a chance to restore Israel’s status as victim, for the world to see.

With no distinct military frontline, the crisis was handled by the Military’s Technological and Logistics Directorate (TLD), an administrative agency that would later turn into the ‘Homefront Command’. The TLD ordered every family and private household in Israel to convert one room into a shelter by taping up all windows and doors against the potential use of nerve gas by the Iraqi military.3 Meanwhile, Israeli media proclaimed the demise of the public shelter, which until the winter of 1990 continued to be a symbol of Israeli resilience. ‘The public shelter is no longer a shared space’, concluded one headline, ‘it is now the private home that will save you’.4 Tasks that in the past belonged to state institutions were gradually transferred to civilians. ‘Private homes would be the first destination of chemical warheads’, announced another headline in one of Israel’s major newspapers.5 The home, no longer imagined as a refuge from the public realm, was now the centre of concerns over security and defence.

To deal with the probability of an Iraqi attack, Israel triggered Civil Defence Regulations that were drafted with the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948 and adopted as a basic law in 1951. These regulations lay down the scheme of communication between the government and the civil population during times of emergency. The crisis resuscitated the need for civil defence and for a strategy that would allow the IDF to efficiently distribute information to each and every citizen, individually. With the looming threat of an attack that would hit private homes, buildings and infrastructure within city centres, Israel delivered a message that communicated a simple principle: protect yourself. This refined resolution of defence singled out the individual as the core unit of national security. By delimiting the home as the target of war, the government was able to delegate responsibilities that are usually handled by the IDF to individual civilians. Simultaneously, the borders of the state, usually marked by fences, barrier and walls, were suddenly shrunk to the scale of private homes. This, as I will show in this chapter, blurred the private and national conceptions of security and helped to reroute domestic media practices to national interests. Civil Defense Regulations, I argue in this chapter, are the unexamined history of what would later shape the appropriation and weaponization of habits.

Civil defence

Although the trail of paper traces the Civil Defense Regulations back to the very foundations of the Israeli state, they were not fully implemented until the beginning of the 1990s. ‘Until 1991 the home front in Israel was fairly protected from terror’, stated Aharon Farkash, the former chief of military intelligence, ‘but with missiles launched from Iraq life has changed: the notion that “my home is my fortress” has crumbled’.6 The inability to preempt what will be the consequences in case Iraq targets private households in Israel quickly replace procedures of self-defence.

Civil defence is more than anything a long list of regulations and protocols that instruct citizens on what to do in case their lives are directly threatened. A closer look reveals the role of these regulations in formulating a channel of communication between the state and the individual. By training, regulating and guiding the civilian to a set of practices, the state can reach directly into the privacy of his or her home and the individual body that inhabits it. More than reproducing the inert subject of disciplinary power through demands and orders, the individual shaped by civil defence becomes actively and intimately engaged in matters concerning security. This activating force, what Michel Foucault would call ‘pastoral power’, is incremental to the personal use of media technologies and their integration into the core of emergency routines.7

The first legal stature of civil defence was formulated in the aftermath of the 1948 war. Its aim was to introduce communication channels between the Israeli state and civilians at home. As early as 1951, these communication channels were institutionalized through the Civil Defence Law that specified the growing need to implement schemes to prepare civilians to manage direct security treats to their private households.8 The new law grounded the necessity to take all measures required to protect the civilian population against attacks by hostile forces, or to limit the adverse results of such an attack, emphasizing the need to save lives. The law further stated that under the unpredictable condition of imminent threat, military procedures should be consigned to the civilians themselves: ‘individuals should take fate into their own hands’.9

The 1951 document titled Civil Defence Regulations opens with the main goals behind civil defence and the defining procedures aimed at mobilizing civilians during times of continued national emergency. The opening words of the chapter allude to the individuating element of the entire scheme, articulating a conception of security that revolves around the single individual:

The defensive layer whereby the individual harnesses any available means to minimise threat through the use of technologies, individual defense kits and the preparedness of the private household for crisis [. . .] the responsibility of one’s safety is in the hands of the individual himself.10

The 1951 Civil Defence Law reflects strong ties between the military and civil sectors of Israeli society. One of the most important factors enabling the strengthening of these ties was the nourishing of the idea of a ubiquitous threat to the survival of the Israeli state. ‘Israel’s national security policy’, writes Anver Yaniv, ‘begins from the assumption that the Arab-Israeli conflict is inherently and unalterably asymmetrical and that the Jews are and will always remain the weaker party’.11 The new civil defence regulations were shaped according to this fallacious notion and by existential fears embedded within the Israeli social fabric. Such fears were expressed in 1951 by Israel’s first prime minister David Ben-Gurion who declared that:

A small Island surrounded by a great Arab ocean extending over two continents [. . .] this ocean is spread over a contiguous area of four million miles, an area larger than that of the United States in which 70 million people, most of which are Arab speaking Muslims, live.12

The Civil Defence Law was backed by Ben Gurion’s assumption that ‘Israel must eliminate the common but pernicious misconception that the army alone can guarantee state security’.13 Security, consequently, must be habituated and personalized. The notion of self-defence poignantly captures this personalizing necessity.

The gist of ‘self-defence’ regulations and the programme for imbedding them into the everyday were largely inspired by experiments and procedures within the United States. In the early to mid-1950s, the US government invested substantial scientific and economic resources into re-imagining the private sphere as the ultimate defence against nuclear warheads.14 Israel’s civil preparation for wartime followed US President Truman’s lead. At the time the Israeli Civil Defence Law was passed, Truman had just inaugurated the new Federal Civil Defence Administration (FCDA). This government office was charged with integrating science, technology and entrepreneurship to develop plans for making people and property safe from attack.15 The FCDA invested all of its resources to find a curative for the nation’s nuclear blues, calling ‘all statesmen and citizens alike to prepare for a new kind of war that would show no mercy for home front civilians’.16 In the 1950s, civil defence was devised as ‘a security program that domesticated war and made military preparedness into a family affair’.17

Anthropologist Joseph Masco argues that the American civil defence project of the early 1950s was not predicated primarily on protection and security of the home, but rather on a national contemplation of ruin.18 In other words, imagining the dismal consequences of a nuclear bomb became the means of perpetuating emergency regulations. By the mid-1950s, it was no longer a perverse exercise to imagine one’s h...