- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1988, the 19 original essays (and three "Sylvia" cartoons) included in this volume deal with the gender-specific nature of comedy. This pioneering collection observes the creation of women's comedy from a wide range of standpoints: political, sociological, psychoanalytical, linguistic, and historical. The writers explore the role of women's comedy in familiar and unfamiliar territory, from Austen to Weldon, from Behn to Wasserstein. The questions they raise will lead to a redefinition of the genre itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Last Laughs by Regina Barreca in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

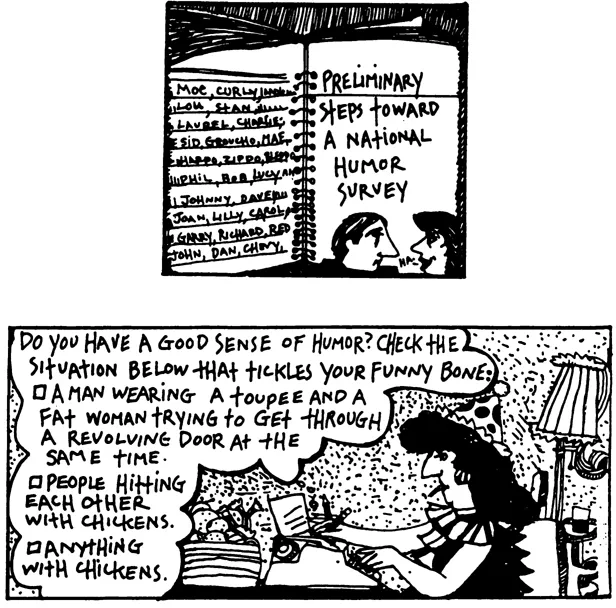

Sylvia

NICOLE HOLLANDER

Ironie autobiography: from The Waterfall to The Handmaid’s Tale

Nancy Walker

Stephens College, Columbia, MO

I

Toward the end of her novel Heartburn, Nora Ephron has her narrator, Rachel Samstat, explain why she has told her story:

Because if I tell the story, I control the version.Because if I tell the story, I can make you laugh, and I would rather have you laugh at me than feel sorry for me. (176-77)

Near the beginning of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the narrator, Offred, makes a similar comment about her role as storyteller:

I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling. I need to believe it. I must believe it.Those who can believe that such stories are only stories have a better chance.If it’s a story I’m telling, then I have control over the ending. Then there will be an ending, to the story, and real life will come after it. I can pick up where I left off.It isn’t a story I’m telling.It’s also a story I’m telling, in my head, as I go along. (39)

Despite dramatic differences between these two novels — Ephron’s comic account of her divorce from Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein and Atwood’s grim futuristic description of the repressive Republic of Gilead — they share an autobiographical method, a focus on the woman telling her own story. Both Rachel Samstat and Offred wish, in the telling, to control the accounts of their own lives, and both narrators reveal a consciousness of the ironic difference between reality and their “stories,” a consciousness that separates the narrator into two “selves” — one that endures the anguish of her own reality and a second self that stands apart and comments, often quite humorously, on the plight of the first.

Margaret Drabble, in The Waterfall, employs an even more overt method to create these two “selves.” By alternating third-person and first-person narratives, Drabble provides a continual double perspective on her character’s life: the story of Jane that is told in the third-person narrative is an edited version of reality created by Jane herself at a later date. The first-person ironic narrator announces her role as “author” of her own story at the beginning of the fifth chapter:

It won’t, of course, do: as an account, I mean, of what took place. I tried, I tried for so long to reconcile, to find a style that would express it, to find a system that would excuse me, to construct a new meaning. ... And yet I haven’t lied. I’ve merely omitted: merely, professionally, edited. (47)

Having admitted that the story of Jane — of herself as Jane, rather than as “I” — is a partial one, this narrator resolves somewhat later to “go back to that other story, to that other woman, who lived a life too pure, too lovely to be mine” (70). Drabble’s narrator thus tells her own story, a story she acknowledges to be a fiction, edited so that she can, to use Ephron’s words, “control the version.” In a similar blending of past and present, third- and first-person narratives, Fay Weldon’s narrator Chloe, in Female Friends, recounts the histories of herself and her friends Grace and Marjorie, shifting constantly from present to past tense, from “I” to “Chloe,” attempting in the telling to discover some pattern or reality. At the end of the novel, Chloe speaks to the reader about this attempt:

Marjorie, Grace and me. What can we tell you to help you, we three sisters, walking wounded that we are? What can we tell you of living and dying, beginning and ending, patching and throwing away; of the patterns that our lives make, which seem to have some kind of order, if only we could perceive it. (309)

As the ironically detached narrator, Chloe presents the stories of these three women as having the kind of logic and inevitability that can be imposed only by the author of fiction.

These four novels by women, published between 1969 (The Waterfall ) and 1986 (The Handmaid’s Tale), represent a significant development in the consciousness and method of the female fiction writer in Britain and America. The consciousness of the social “self” as somehow fictive, created in large part by cultural rules and expectations, leads the author to use an ironic method in which the central character or narrator is presented as a creation of her own imagination. The voice of the ironic self comments with exasperation or amusement on the thoughts and actions of her “created” self, while viewing her sympathetically, as one hopelessly enmeshed in the absurdities of women’s lives. The resultant comedy demystifies women’s existence in the late twentieth century; the mutability of self points up the arbitrary nature of the restrictions that the women’s movement has fought so vigorously during these years.

From the late 1960s to the present, novels by women have increasingly been biographical or autobiographical in method, if not usually in fact, depicting the progress of individual women toward greater autonomy and fulfillment during a period of social upheaval. Judith Rossner’s Nine Months in the Life of an Old Maid (1969), Gail Godwin’s The Odd Woman (1974), Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room (1977), Marge Piercy’s Fly Away Home (1984), and many others have even reflected in their titles a thematic concern with change, space, and status — a quest for self-definition rather than definition by the culture. Nor is this recounting of a woman’s struggle for control over her own life an entirely new phenomenon in English and American fiction by women. Fanny Fern’s 1855 novel Ruth Hall, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, and Virginia Woolfs Mrs Dalloway, among others, are precursors of the contemporary women’s novel in their investigation of a female character’s more or less successful attempt to define the terms of her own life. What distinguishes the recent works by Drabble, Weldon, Ephron, and Atwood is their ultimate refusal to take seriously the cultural prescriptions that seek to define their central characters — a refusal that is reflected in the use of an ironic mode.

Traditionally, the women’s novel — certainly the popular novel — has affirmed rather than questioned the values of the culture. As Lynne Agress points out in The Feminine Irony, it was not until Fanny Burney’s Evelina, in 1778, that women began to write about women, and in the early nineteenth century, women’s novels that featured female main characters tended to reinforce the submissiveness and Subordination that were touted as ideal feminine traits:

Their works were mainly didactic: as writers they would guide women in performing their proper roles as subordinate creatures, as helpmates to men. In attempting to be messiahs to women, they often ended up as the devil’s disciples.So long as women were willing to subscribe to the subordinate role created by society and endorsed by most women writers, their lives could not really change. (172-73)

The term “irony” in the title of Agress’ book, in fact, points to the very lack of this quality in the consciousness of the early female novelist. That is, without skepticism about the culturally-sanctioned subordination of women, the novelist could achieve no distance from it, and therefore accepted — and promoted — it as part of an immutable social fabric.

The contemporary novel by women has unquestionably challenged the established social fabric, though not as overtly as has the distinctly ironic novel. By presenting female characters who break away from traditional roles and bonds (marriage, motherhood, etc.), as do writers such as French, Piercy, and Rossner, the author implicitly indicts the system that has made such escape necessary for a woman’s self-fulfillment. The double vision of the ironic novel, in contrast, makes explicit the flaws or the plain evils of the culture by exposing them to the narrator’s clear-eyed vision and thus demonstrating their absurdity. That is, this critique is explicit if the reader is able to “read” the irony. Wayne Booth, in A Rhetoric of Irony, maintains that the reading of ironies requires four steps, which are usually accomplished almost simultaneously. First, the reader must “reject the literal meaning” of the author’s words because of an incongruity “among the words or between the words and something else that he knows.”1 Secondly, the reader casts about for alternate meanings. Third, the reader makes a decision “about the author’s knowledge or beliefs.” “It is,” Booth notes, “this decision about the author’s own beliefs that entwines the interpretation of stable ironies so inescapably in intentions.” Fourth, and finally, the reader must reconstruct a meaning that he believes is the author’s actual intended statement. “Unlike the original proposition, the reconstructed meanings will necessary be in harmony with the unspoken beliefs that the reader has decided to attribute to [the author]” (10-12).

Thus in Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, when the Aunts, who instruct the Handmaids on their duties, change the wording of the Bible verses the Handmaids are required to memorize, or attribute to the Bible statements from other sources, they depend upon the Handmaids’ inability to “read” ironies. Atwood, on the other hand, depends upon her reader to read them quite clearly. For example, as Offred describes the occasion of one of the Handmaids giving birth, she remembers one of the Aunts’ brainwashing refrains:

From each, says the slogan, according to her ability; to each according to his needs. We recited that, three times, after dessert. It was from the Bible, or so they said. St. Paul again, in Acts. (117)2

Even if the reader does not initially notice the substitution of the feminine pronoun “her” in this statement from Marxist doctrine — a substitution that accords with the Gileadean use of women for the needs of men — he or she will recognize that the statement is not from the Bible, as the Aunts claim. Furthermore, Offred is herself close to seeing the incongruity, as revealed in the phrase “or so they said.” The ironic juxtaposition of the religious and the secular/political (or, rather, the incorporation of the latter into the former) indicates the extent to which the rulers of Gilead bend reality to their own purposes.

The continual cross-referencing of past and present in these ironic novels allows for clear examples of the second kind of ironic statement that Booth mentions, in which the incongruity exists between “the words and something else that [the reader] knows.” Such ironic statements are frequent in Weldon’s Female Friends. Early in the novel, for example, Chloe begins a description of a scene involving her friend Grace as follows:

Envisage now another scene, one summer Sunday some twelve years later, when Grace is in the middle of her dream marriage to Christie. (Grace has a dream marriage the way other women have — or don’t have — dream kitchens.) (61).

Not only is the statement made inherently ironic by the concept of the “dream” and the undercutting of the negative phrase “or don’t have” — both of which expose by inversion the reality of Grace’s marriage — but it is also incongruous alongside Chloe’s earlier description of Christie as “arch-villain of a decade” (16). Therefore, it comes as no surprise to the reader that Grace’s “dream” is shattered on that “summer Sunday.”

These four novels by Atwood, Weldon, Drabble, and Ephron, despite their differences in setting and style, share several important characteristics, all of them linked to the use of irony — both verbal and situational — that reveals a particular relationship between women and social reality, women and the concept of “self.” Each has a narrator who self-consciously and deliberately tells her story, addressing the reader directly as she detaches herself from the everyday realities that her undetached “self” experiences. In his monograph Irony, D. C. Muecke identifies several “basic features” of irony, one of which may be identified by a number of different terms: “detachment, distance, disengagement, freedom, serenity, objectivity, dispassion, ‘lightness,’ ‘play,’ urbanity” (35). Muecke continues by explaining the relationship between this “detachment” and the stance of the ironist:

This lightness may be but is not necessarily an inability to feel the terrible seriousness of life; it may be a refusal to be overwhelmed by it, an assertion of the spiritual power of man over existence. (36)

The narrators in these novels clearly feel the “terrible seriousness of life,” but their strength is their refusal to be “overwhelmed” by it.

In addition, each author employs a plot structure that continually juxtaposes past and present in order to demonstrate the influence of past upon present in the formation of identity and behaviour — in particular, to examine changes, both positive and negative, in women’s lives during the past twenty years. Finally each novel displays a feminist consciousness that is capable, by means of ironic distance, of viewing the subordination of women as an absurdity rather than a necessity. The resulting effect is comic — wildly so in Heartburn, grimly so in The Handmaid’s Tale — in the sense that the reader is forced to see as ludicrous some fundamental assumptions about woman’s nature and role in society.

II

Although none of these four novels is, properly speaking, an autobiography (Heartburn comes closest, but Ephron intended it to be read as fiction), all share some of the classic elements of autobiography: the first-person narration, and especially the emphasis on detailing the development of a self .3 For women writers, autobiographical writing has been problematic because the concept of selfhood has itself been problematic. Women have traditionally been defined in relation to others — as daughter, sister, wife, mother — rather than as autonomous entities, and this fact has affected the nature of women’s autobiographical writing. Mary G. Mason has pointed out that in the earliest autobiographical writings by women in English, from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries, there is a dual consciousness:

The self-discovery of female identity seems to acknowledge the real presence and recognition of another consciousness, and the disclosure of female self is linked to the identification of some “other.” This recognition of another consciousness — and I emphasize recognition rather than deference — this grounding of identity through relation to the chosen other, seems ... to enable women to write openly about themselves. (210)

The most common “others” have been God and husbands or fathers, depending on whether the autobiography is spiritual (Anne Brad-street’s “To My Dear Children”) or secular (Margaret Cavendish’s True Relation) in nature.

In the contemporary ironic novel, in contrast, not only is there a “self” that exists without necessary relation to an “other,” but this self is capable of self-scrutiny by a separate part of her consciousness, in the form of the alternate narrator. This splitting of the self is directly related to cultural realities, as women have increasingly adopted non-traditional roles. Thus, in the late 1960s, the narrator in Drabble’s The Waterfall fee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- I Sylvia

- II Sylvia

- III Sylvia

- About the Contributors

- Index