eBook - ePub

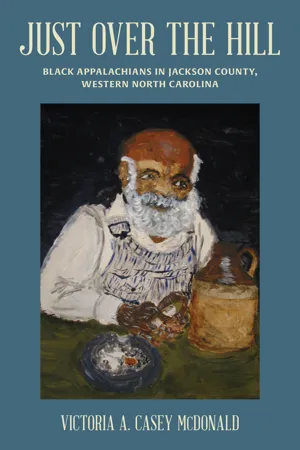

Just Over the Hill

Black Appalachians in Jackson County, Western North Carolina

- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Just Over the Hill

Black Appalachians in Jackson County, Western North Carolina

About this book

Long before the term “Affrilachia” became popular, Victoria A. Casey McDonald spent decades gathering the stories of her family and neighbors in North Carolina’s Jackson County. Her book, Just Over the Hill: Black Appalachians in Jackson County, Western North Carolina, presents a collection of narratives that illuminate the lives of African Americans in the region. These stories include her grandmother’s, Amanda Thomas, who was born into bondage. The biographies and histories continue through the twentieth century and feature educators, soldiers, factory workers, ministers, athletes, and other community members. Originally published in 2012, this edition of Just Over the Hill with an afterword Marie T. Cochran continues to speak for these resilient individuals to generations to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Just Over the Hill by Victoria A. Casey McDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION I

(1825-1900)

INTRODUCTION

The history of the African Americans in Western North Carolina began long before the Civil War. As mentioned in the foreward, in the early 1800’s, Daniel Bryson herded 140 slaves into the area that was to become Jackson County from across Balsam Mountain and settled in the Beta area. Others came across Soco Gap. Slavery became a way of life for about a third of the white population. Most of these slave owners had less than ten slaves. Therefore, most masters and his slaves worked together in fields.

With this working relationship between the slave and master, there was a close bond. In the census on the slave schedule of 1860, it appeared that most slaves lived within a family unit. Sometimes, the master had to sell a slave for debt or give a slave as wedding gift to their daughter.

When the Civil War began and the master went off to fight for state’s rights, while trusted slaves were left behind to take care of the master’s home place. Other slaves went with their masters as a body servant. In the individual stories told through the eyes of the slaves or former slaves, one can see that the African Americans defended what they believed was their homeland.

As you read these stories of the African Americans in Jackson County, one can see the trust the slave owner and slave had between them. In other words, the slaves found a safe haven in these mountains when the Civil War ended. To survive, the former slaves relied on the whites to nurture them until they realized they needed to establish their own churches, schools, social organizations and their own businesses or professions.

The slaves who “jumped the broom” had their marriages legalized. Thus the African Americans began to create their own communities, which were situated just over the hill from each other. Most African Americans lived in a community that had a white Appalachian living next door.

Where It All Began: My Great-Great Grandmother

(From the West Coast of Africa, to a Caribbean Island, to Virginia, to the mountains of North Carolina)

Oconaluftee

Stripped from our homeland

Held in a dungeon down by the riverside Waiting for our fate

Looking at some strange being with hair on his face

An animal, not from the rainforest, to eat our dark meat

Who were these strangers?

What did they want from us?

What was our crime to be chained like an animal?

Questions that had no answer!

We were Africans, but we were the strangers.

Held in a dungeon down by the riverside Waiting for our fate

Looking at some strange being with hair on his face

An animal, not from the rainforest, to eat our dark meat

Who were these strangers?

What did they want from us?

What was our crime to be chained like an animal?

Questions that had no answer!

We were Africans, but we were the strangers.

We looked at each other with fear in our eyes

What would be our fate?

Words we could not understand shouted through the gloom

Cat-of-nine-tails whipping our backs

In chains we moved and followed them.

The sandy shores of my homeland squeezed between my toes

Leaving a perfect footprint for someone to follow,

But when I looked back, it was gone

Mangling in the sand with other footprints

And I cried because I knew it was gone.

What would be our fate?

Words we could not understand shouted through the gloom

Cat-of-nine-tails whipping our backs

In chains we moved and followed them.

The sandy shores of my homeland squeezed between my toes

Leaving a perfect footprint for someone to follow,

But when I looked back, it was gone

Mangling in the sand with other footprints

And I cried because I knew it was gone.

The ocean waves were angry now,

As we are piled into a small boat, chained together

Looking way out beyond the waves

“What is this I see?

Water, water, water, surrounding us

Like the solid earth would never again exist!”

I shouted my ancestors’ names, but it fell on deaf ears.

A bigger, stranger boat bounced on the horizon

“Will this be my home?

Will this be my home?”

As we are piled into a small boat, chained together

Looking way out beyond the waves

“What is this I see?

Water, water, water, surrounding us

Like the solid earth would never again exist!”

I shouted my ancestors’ names, but it fell on deaf ears.

A bigger, stranger boat bounced on the horizon

“Will this be my home?

Will this be my home?”

We are herded on the boat like the wilder beast

Whipped and shoved, trying not to entangle the chain

Some of us stumbling down

But the whip demanded us to get up.

The breeze from the ocean was now on our faces

The smell of salty water filled the air.

We breathe in deeply, as they herded us down below.

Into a dark, dark hole with little fresh air

I smelled the remnants of human remains

And I know I will be forever lost!

Whipped and shoved, trying not to entangle the chain

Some of us stumbling down

But the whip demanded us to get up.

The breeze from the ocean was now on our faces

The smell of salty water filled the air.

We breathe in deeply, as they herded us down below.

Into a dark, dark hole with little fresh air

I smelled the remnants of human remains

And I know I will be forever lost!

Chained in this dark, dark hole

Together with people I did not know

What was my crime?

The splashing water against the boat sang a song.

It said, “Gone are the days when my heart was happy and gay.

And yet my ancestors will know me not

I am nothing. .. A piece of black meat!

Lying here, waiting to be devoured by pale hairy creatures.

Let me die! Let me die!”

But somehow I willed my soul and body to live.

Together with people I did not know

What was my crime?

The splashing water against the boat sang a song.

It said, “Gone are the days when my heart was happy and gay.

And yet my ancestors will know me not

I am nothing. .. A piece of black meat!

Lying here, waiting to be devoured by pale hairy creatures.

Let me die! Let me die!”

But somehow I willed my soul and body to live.

Days turned into nights as nights turned into days.

Eat, sleep, relieve thyself, and breathe in the stench.

How long I did not know. . .

But fresh air came through the dark, dark hole.

Land was near and I was still alive.

“Where are we?” my soul cries

The hatch was opened one more time

And the chains loosed from my bed of horror

A few of us were herded on deck

To be free! No...just to be cleaned up.

Eat, sleep, relieve thyself, and breathe in the stench.

How long I did not know. . .

But fresh air came through the dark, dark hole.

Land was near and I was still alive.

“Where are we?” my soul cries

The hatch was opened one more time

And the chains loosed from my bed of horror

A few of us were herded on deck

To be free! No...just to be cleaned up.

The stench of the bowels still in my nose,

As fresh air strangled my very soul

Water still seemed to surround us

An inner being shouted, “No, no, no!”

For this was not my homeland

Only strangers I’m to see

Voices I could not understand, speaking all around me.

“Who am I?

I am an African.

I am lost in a world I do not know.”

As fresh air strangled my very soul

Water still seemed to surround us

An inner being shouted, “No, no, no!”

For this was not my homeland

Only strangers I’m to see

Voices I could not understand, speaking all around me.

“Who am I?

I am an African.

I am lost in a world I do not know.”

We have landed on some island

About the size of my kingdom abroad

But no land seemed to be near us

Even the Natives seemed to stand in “AH!”

Of the bearded strangers who have taken control.

I was to begin my life all over again

Reborn into their way of life

Everything taken away from me

I was a person without a country

I was a person without a name.

About the size of my kingdom abroad

But no land seemed to be near us

Even the Natives seemed to stand in “AH!”

Of the bearded strangers who have taken control.

I was to begin my life all over again

Reborn into their way of life

Everything taken away from me

I was a person without a country

I was a person without a name.

I was drilled into submission

I was a helpless, flightless bird

My wings have been broken

I have learned to know my new name

My African birth name now forgotten I have been seasoned

My life started anew in this strange world

I heard words like “...the mainland....”

“Where can that be?”

I was sold at auction.

I was a helpless, flightless bird

My wings have been broken

I have learned to know my new name

My African birth name now forgotten I have been seasoned

My life started anew in this strange world

I heard words like “...the mainland....”

“Where can that be?”

I was sold at auction.

“Martha. . . Is this really me?”

Sold to a slave captain to be taken to the mainland

The mainland in a place called Virginia.

Put back in the bowels of a ship

Back to stench and horror,

But I listened and I had learned

I know now that I was a slave

And yet I wondered how long I would be enslaved

Not until death, “Just do as you’re told!

Freedom will come!!!”

Sold to a slave captain to be taken to the mainland

The mainland in a place called Virginia.

Put back in the bowels of a ship

Back to stench and horror,

But I listened and I had learned

I know now that I was a slave

And yet I wondered how long I would be enslaved

Not until death, “Just do as you’re told!

Freedom will come!!!”

Virginia. . . The port was very busy,

Buzzing with people, mostly with white people

Dressed in what I knew was their Sunday best

Walking with canes to try to look important

Examining us...slaves...like we were cattle

To be bred on the plains of Africa

I tried to think of my homeland

For a slave was important to the kingdom

People were an asset, not property...

“Am I just a piece of property!!!”

Buzzing with people, mostly with white people

Dressed in what I knew was their Sunday best

Walking with canes to try to look important

Examining us...slaves...like we were cattle

To be bred on the plains of Africa

I tried to think of my homeland

For a slave was important to the kingdom

People were an asset, not property...

“Am I just a piece of property!!!”

Standing on the auction block, shivering in the heat of the day

I looked at all the buyers and tried to find a kind face.

Bearded ones, I could not see, their faces were hid

There was one who face was clean shaven

His piercing eyes seem to crawl out of their sockets,

While no smile crossed his white face

I looked away from him, as he looked my way

Was there kindness there?

“Who am I to say?

Who am I to say?”

I looked at all the buyers and tried to find a kind face.

Bearded ones, I could not see, their faces were hid

There was one who face was clean shaven

His piercing eyes seem to crawl out of their sockets,

While no smile crossed his white face

I looked away from him, as he looked my way

Was there kindness there?

“Who am I to say?

Who am I to say?”

The auctioneer did his thing to sell us

He made us hold our head erect.

He made us show our teeth

He felt our arms to tell them that we were strong

Good to work in the field

Strong!

Strong enough to endure the pain of lost identity

Strong enough to endure the stench of human waste

Strong enough to begin a new life

Strong enough!!

He made us hold our head erect.

He made us show our teeth

He felt our arms to tell them that we were strong

Good to work in the field

Strong!

Strong enough to endure the pain of lost identity

Strong enough to endure the stench of human waste

Strong enough to begin a new life

Strong enough!!

I was bought by William Holland Thomas

Taken away from Virginia to a place called North Carolina

In the hills of North Carolina, I went

And there I was indoctrinated into the culture of the day.

Yet would I stay there?

Would I be sold again and again?

Never knowing if I belonged.

Submersing myself into a new, unfamiliar, culture

This Appalachian culture

That my descendants now call . . .

their ancestral home.

Taken away from Virginia to a place called North Carolina

In the hills of North Carolina, I went

And there I was indoctrinated into the culture of the day.

Yet would I stay there?

Would I be sold again and again?

Never knowing if I belonged.

Submersing myself into a new, unfamiliar, culture

This Appalachian culture

That my descendants now call . . .

their ancestral home.

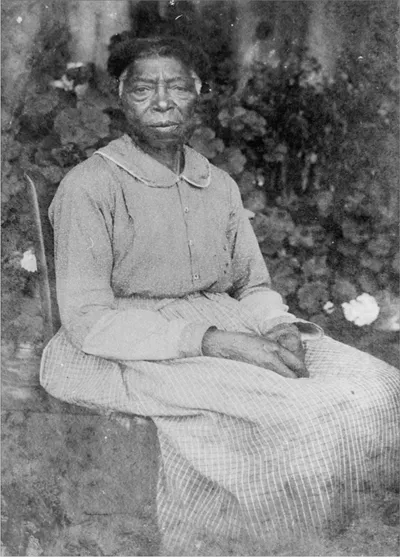

Amanda Thomas: My Great-Grandmother

Stekoa Fields, Montieth Gap

Amanda Thomas was born in Stekoa Fields which was the name of William Holland Thomas’s home. According to her death certificate, she was born on July 3, 1839. My greatgrandmother was a slave of Thomas and her mother, Martha, was the first slave he purchased. Traditionally, it is stated that in 1825 Will Thomas went to Richmond, Virginia and purchased her at an auction. At the time, Martha was about eight years old.

Very little is known about Martha or Amanda, but it is known that Amanda smoked a corn cob pipe. Growing up around Stekoa Fields, she knew the Cherokees. When she was fifteen, Will Thomas married Sarah Love from White Sulphur Springs near Waynesville. It was perhaps through this marriage that Amanda met her husband-to-be, William (Bill) Hudson Casey. It seemed that William’s older brothers, James and George, were conscripted for ninety-nine years to James R. Love, Sarah’s father.

With the approaching Civil War, it is traditionally stated that Mr. Love was gathering strong young bucks to defend his home. It appears that Bill’s mother Harriet was a free black person, but conscripted her sons to Mr. Love. Bill was too young to be conscripted.

At any rate, Amanda and Bill probably cohabited as the Civil War was raging, or shortly after the war. Like most slave marriages, they could have jumped the broom. Three years after the Civil War, Amanda and Bill legalized their marriage. On January 14, 1869 they were married by the Justice of the Peace, C. C. Spake.

In 1866 Amanda had a child. On his death certificate, Bill Casey is listed as his father. They named him Mountville Sherman. Researching the Civil War history, Mountville was a name of a small town in Virginia. In 1861, the North and South fought a battle there. Perhaps, she heard about the battle and named her first born son Mountville.

His middle name Sherman was a common name that many former slaves named their male child. Just listening to the feats of General William T. Sherman march through Georgia destroying the Confederacy, Amanda believed that she would be free. By destroying town after town meant that slavery was ending.

The war ended just shortly before Mountville was born. Although Bill and Amanda were free, they continued to live at Stekoa Fields. As matter of fact, all her six children were born there.

In 1892 in the Township of Webster, Bill and Amanda purchased land. At that time Webster’s boundary went all the way to Cullowhee, which included Montieth Gap. They bought a mountain tract from M. L. Deitz and his wife D. J. Deitz for $300 dollars. The deed stated…”To have and to hold all the appurtenances there…to belonging including wood, water, minerals, fossils, etc. To have and hold onto the use of the said William Casey and his heirs and assigns forever.” At the time of the purchase, Mountville was twenty-six and baby Charles was eight. While the children felt that they were living in slavery, the purchase of the land made them feel free. Bill must have felt really free, because he left Amanda and went to live with Rosette Hyatt in Little Savannah.

With Bill gone, Amanda became the matriarch of the Casey family. Along with her oldest son, Mountville, she held the family together. When Mountie died in 1914 of typhoid feverher second oldest son, George Power, took over. In 1905, he had married Sadie Hooper. Within Amanda’s household was her extended family, which included her daughter Cordelia and her two children, Robert Lee and Cary May.

Amanda saw many changes. Along with George’s wife, she wanted her grandchildren to have an education. From the one room school to a consolidated one in Sylva, she praised God for it. On December 8, 1924, Amanda died at 4:30 am from pneumonia.

Long Journey Home: Granny Ede

East Fork Community

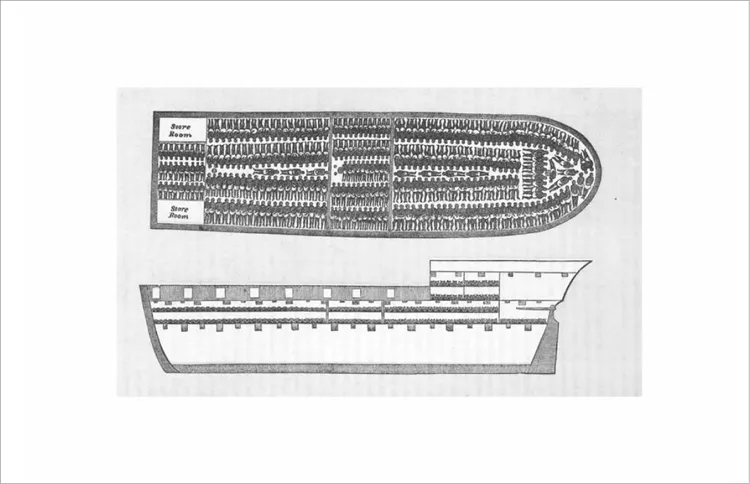

In about 1825, slavers in Guinea on the west coast of Africa took a little African five-year-old girl with blue eyes and her mother. With other Africans, she and her mother found herself on the sandy coast in chains. There were Africans of different tribes with languages she could not understand. Chained with her mother, they did not know what fate awaited them.

The bearded-faced slavers spoke a strange language, but their action told the little girl and her mother that they wanted them to get in the small craft to board the big boat lying off the coast. Without knowing where they were going, the two were forced on board by foreign men who ordered them into the craft. Her mother protected her as the other Africans crowded in on them. Frightened they huddled together.

When they got to the slave ship, the crew chained them together in the hull of the ship with the others. There was no space to sat up, so they laid side-by-side all though the journey to a new land. The ship rocked and rolled. Roaring water slapping against the hull of the ship was like a continuous rhythm that frightened them. Moans and groans filled the stagnant air, while the smell of feces and urine made the children sick. Others died and the bearded white men dragged them out. From time to time, the crew herded them up on the deck and cleaned the hull.

At last, the ship docked in Virginia. The motion of the waves stopped. The hull hatch opened to a blue sky, which welcomed them. The fresh air forced itself in their nostrils and the little girl wondered if this was the end of her journey. Her father had remained in Africa and she was somewhere across the big water. Her only family was her mother, who tried to protect her.

The next day, all the Africans were put on the “Slave Block.” Mother and daughter held on to each other. It seemed they did not want to be separated. They did not know the strange language, but it appeared that the other Africans were being sold. She saw money exchange between the white men after the bidding was over.

Now they stepped up on the block. Men came and examined them. They looked at their teeth as if they were horses. They felt their arms and legs to make sure that their limbs were strong. The girl hugged her mother as the white men bidded. A family living near Petersburg bought them. The first thing that the family did was to take away their African names. The little girl’s name was changed to Ede and her mother became Chloe. Slowly they learned English and worked for their Master and Mistress.

However things didn’t work out, the mother was sold on the Petersburg slave market. Now eight-year-old Ede was all alone and working in the tobacco field. She could crush a tobacco beetle with her bar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface

- Section I (1825–1900)

- Section II (1901–1930)

- Section III (1931–1950)

- Section IV (1950–1965)

- Back Cover