![]()

What is real?

Mankind is special. Wrong.

Living things made us what we are.

– Charles Darwin

Space and time are different. Wrong.

Space and time are a matter of perspective.

– Albert Einstein

The world is individual objects. Wrong.

The world is interconnected events.

– Alfred North Whitehead

Mistaken Reality

WE OFTEN SPEAK OF “TWO”.

WHEN IT IS NOT TWO.

I marvel when I see our different ways to approach reality. In the Western world we dissect it into alleged components and analyze them in the hope to understand. The Eastern world is uplifted by grasping reality as one big picture.

Looking back, analytical procedure—especially technical and medical—has made good strides for all of us, for example the development of high-resolution telescopes and microscopes. But holistic thoughts were always a step ahead of scientific quantum leaps. There were three remarkable minds from the Western world who thought holistically too: natural scientist Charles Darwin, physicist Albert Einstein and the relatively unknown philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead (see figure 6).

Fig. 6: Darwin, Einstein, Whitehead

We will look at the revolutionary ideas of Darwin, Einstein and Whitehead in this chapter. Three excellent scientists have left behind a huge spiritual legacy for humanity that can help us stop self-delusion. Don’t worry—it won’t be difficult at all. I will describe everything with texts and pictures.

At first glance, Darwin, Einstein and Whitehead don’t seem to have anything at all in common. Darwin died when Einstein was only three years old. It’s true that Einstein and Whitehead met each other in 1921 at King’s College in London,15 but they couldn’t agree on a common interpretation of the theory of relativity. After that, they probably never had any further contact with each other again. Only after we take a more careful look at the work of all three of these scientists, we see that they were pursuing precisely the same secret of nature without being aware of it: Reality does not consist of parts, but it unfolds as one big picture! Each of them revealed this secret to his own scientific field by vigorously challenging traditional schools of thought. Eventually, all three scientists died without knowing that their secret would emerge in our time to be a fundamental cosmic concept.

Where does this cosmic concept pop up? And what is its meaning for us and for our one big question: Why are we here? Without giving too much away, I believe that the ideas of Darwin, Einstein and Whitehead will deeply transform our understanding of the world: Darwin with his theory of evolution, Einstein with his theory of relativity and Whitehead with his process philosophy—to interpret the world as events and not as objects.

All three theories challenge something that almost everyone assumes to be true: mankind as the crown of creation, time and space as absolute, and a world consisting of objects. In all three theories something immutable is replaced by something mutable. And all three theories overcome the separation of something which only seems to be different. Although the approaches couldn’t be more different (Darwin was working on finch beaks among other things, Einstein on space and time, Whitehead on mathematical logic), all three theories suggest that we often speak of “two” when in reality it is not two.

Two or Not Two?

That’s the question! Our senses and brain play tricks on us with reality. We perceive reality as “objects” that exist at a certain time and place—that’s why we split reality apart into space and time. But Albert Einstein will soon tell us that there is no space or time. Reality is beyond space and time. Here comes an example: How many do you see in figure 7?

Fig. 7: How many do you see here?

Figure 7 shows an apple and a pear, two pieces of fruit. Does the figure show two coins too? No, it does not. They are really the front and back of the same coin. Only because both sides are spatially separated in the figure, many people assume that they see two coins. What’s very apparent here may not be so clear in many illusions that we also assume to be reality.

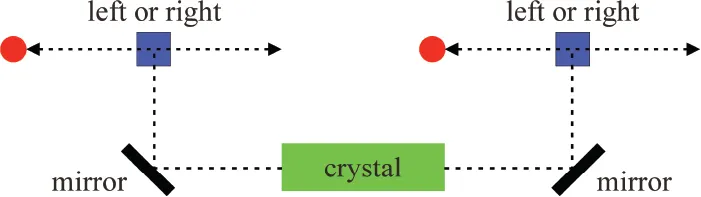

We can see how distorted we perceive reality at times from experiments that verify the activity of entanglement. We physicists speak of “entangled particles” when they had once interacted somewhere and no longer act like individual objects—even when they have moved far apart from each other. Erwin Schroedinger had predicted the existence of these particles in 1935,16 but experimental proof didn’t succeed until 47 years later.17 Entangled particles can be produced with lasers and special optic crystals (see figure 8). Somehow these particles have the remarkable ability to “know” how their counterpart acts during an experiment: If the particles are simultaneously given the choice to turn left or to turn right, both particles make the same decision together. And it doesn’t matter at all how far apart they are from each other!

Fig. 8: Entangled light particles (marked red)

In order to understand the full extent of an entanglement, let’s assume for the sake of simplicity that we were not observing light particles, but cars. One car is driving to New York, the other to Washington, D.C. Entanglement means: Whenever the car in New York turns left, then the car in Washington, D.C., will simultaneously turn left as well (see figure 9). And simultaneously means: While doing this, there is no information exchanged between the two cars. What we’re really saying here is that the fastest that information can travel is at the speed of light,18 so any exchange of information comes with a time-delay. To transmit information from New York to Washington, D.C., in an approximate line-of-sight distance of 200 miles would require at least .001 seconds.19 Entangled particles “know” about each other without having to communicate at all. Albert Einstein spoke of a “spooky action at a distance”,20 because every particle is immediately aware about what is happening to its counterpart. The intriguing question is: Is it two or not two?

Fig. 9: Simultaneous decision made in two different cities

There’s only one conclusion: Entangled particles aren’t two individual objects, but one whole. This whole has the remarkable ability to be simultaneously present at different places at the same time, that is, it transcends space. But one car simultaneously travelling in different places (New York and Washington, D.C.) contradicts our concept of reality. So our idea of structuring the world according to objects is deceptive because we suppose that an object should always be at its “correct” place at a specific time. What we think we see as two individual objects are not always two.

Entangled particles don’t always stay entangled. Performing a measurement voids the entanglement—the whole becomes particles. But the whole never consists of particles, so it is misleading to speak of “entangled particles”. Even the term “entanglement” doesn’t get anywhere because it doesn’t lead us to any new insight. It’s only hiding what doesn’t fit into our usual conception of the world. What I really think is: Entanglement is a phenomenon that forces us to make a paradigm shift. When we interpret the world no longer as objects, then all of the confusion about “entanglement” goes away and the answer falls in our lap.

Alfred North Whitehead will soon invite us to interpret our world as events. We would no longer have to bring up our example of the remarkable car that is travelling in two places—New York and Washington, D.C.—at the same time, but only the event of turning left. We’re really not saying anything against such an event occurring simultaneously in New York and Washington, D.C. It can also rain or snow simultaneously in both places. The same event can happen everywhere at once in the cosmos without our having to bring up the idea of “entanglement” to understand it. But this world view has a price. As soon as we interpret reality according to events, something will be missing that many people absolutely can’t do without: individuality. It doesn’t matter who is doing what in a world of events. What matters is what’s happening—the events themselves.

You could now argue that entanglement is just a phenomenon of the quantum world. But there is increasing evidence that what we see in the macroscopic world can also be entangled. Entanglement among atoms is already a fact,21 and empathy among human beings is a phenomenon that comes very close to entanglement. There are people who are so closely in sync with each other that they know about each other without communicating at all. They have a “common consciousness”. Even trees in the forest seem to “know” how each other is doing.22

A possible explanation for these observations gives us today’s standard model of astrophysics: The cosmos started about 14 billion years ago from a big bang and from one point.23 At that time everything was very close to each other which means that there was a very strong interaction. It is precisely this situation that also triggers entanglement. It is our biggest mistake to consider material objects—that are no longer close to each other today—as individuals. They still are one whole, but we easily overlook this fact when focusing on the objects and disregarding the “stuff” in between these objects. All objects are embedded in something that Buddhists call “emptiness”. This applies to atoms, trees and also to us human beings. It’s the disregard of emptiness that causes the illusion of the self as an individual!

Shankara’s Rope

So everything in the cosmos can only be understood as one thing—not as a plurality, not two. Inseparable unity is also the fundamental thought of Advaita Vedanta, a far-eastern philosophy of life. It is based on the Vedas, the oldest writings of India. For centuries, they were handed down by the great masters to the next generation. The teachings reached their peak in the 9th century A.D. under Adi Shankara who is still known today as one of the greatest philosophers and religious teachers of India.

“Shankara” comes from Sanskrit which is the liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism. It consists of sham (English: good) and kara (English: to cause), so “Shankara” is someone who causes good. The concept advaita (pronounced: “a-dvaita”) is Sanskrit also. The root word dvaita (English: duality, “two-ness”) means that something can be dissected into parts. Adding the syllable “a” to the word dvaita means that it is not correct to speak of parts. Reality is one big picture—and that’s why it has no parts.

Shankara himself loved to speak of a parable24 that he valued very highly: Someone enters a dark little shack and can’t see clearly because of the darkness. He suddenly thinks he sees a snake in front of him. Could it be a deadly snake with poisonous venom? He is petrified with fear of losing his life. But the “snake” wasn’t mov...