eBook - ePub

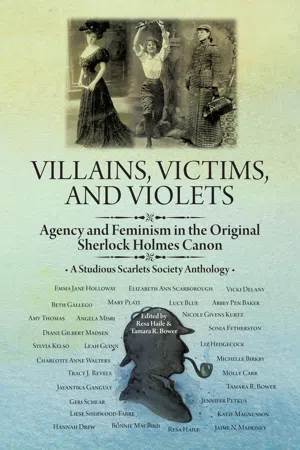

Villains, Victims, and Violets

Agency and Feminism in the Original Sherlock Holmes Canon

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Villains, Victims, and Violets

Agency and Feminism in the Original Sherlock Holmes Canon

About this book

Modern writers have reconsidered every subject under the sun through the lens of Sherlock Holmes. The overlooked subject is agency: the opportunities available to these women for independence and control. What we find all too often are the silences around

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Villains, Victims, and Violets by Resa Haile and Tamara R. Bower in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Feminist Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IV

Restrictions and Allowances for Women in the Most Important Matters: Love and Marriage

“I think that there are certain crimes which the law cannot touch, and which therefore, to some extent, justify private revenge.”

Sherlock Holmes, “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton”

“He and his master dragged me to my room.” Strand Magazine, 1908, “Wisteria Lodge” Arthur Twidle (1865–1936)/Public domain

“I Am Not the Law”: Limits and Expansions of Women’s Agency in the Sherlock Holmes Stories

Sylvia Kelso

What precisely is “agency”? In everyday terms, according to Merriam Webster, “agency” is defined as “the capacity, condition, or state of acting or exerting power.” In his book Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice, Chris Barker, a prominent social scientist, agrees that it is “the capacity of individuals … to make their own choices,” but limits such choices by “structures” that include class, religion, gender, ethnicity, and “customs.” In life, wealth and historical period might be added. In fiction, there’s the genre and the writer’s culture to consider.

In the Holmes stories, several such structures affect the moral arithmetic of pros and cons whose sum determines a major or mid-level character’s fate. Religion is absent, but ethnicity, class and gender matter visibly. Wealth, not mentioned by Barker, counts rarely but powerfully for both genders, and beauty and independence matter for women. Most important are matters of love and/or marriage. All these factors can be negative or positive, depending on case and context, but women’s gender concerns are inflected by a cluster of cultural assumptions from the period.

Central is the increasingly middle-class hegemonic Woman’s ideal that spans Conan Doyle’s era: domestic, unemployed, keeping servants, genteel and gentle, and above all, modestly asexual. In contrast, the Scarlet Woman handily excludes both lower classes and active female sexuality; but there is also a near-terror of women’s violence, the more fearsome because women are supposed to be meek and gentle, where men are not. In the Holmes stories a fourth cultural assumption emerges, a form of “chivalry” toward the weaker sex, particularly women jilted, deserted, or abused inside marriage.

Holmes’ women are largely white, British, and some form of middle-class, with a scattering of ethnicities, one Russian, one Greek, one Italian, one German, four Americans, three Australians, one a maid, and three or four “South Americans” whose nationality is subsumed under their Latin ethnicity. By Conan Doyle’s time women’s activism had operated since the 1850s; married women had kept property from 1875, and had custody of children since 1839; women had entered nursing and education from the 1860s, reached university from 1869, and the medical profession from 1874, while they could work as typists at least in the 1890s, according to Lisa Tuttle’s Encyclopedia of Feminism. Yet Holmes’ women include only four governesses, two typists, one with her own struggling agency, and a prima donna in the then-dubious profession of opera. There are no main character working-class women, but one circus performer, less than five aristocrats, and three women with inherited wealth.

Aristocratic rank always tested the female stereotype; the oncoming independent woman is far more disturbing, but most of Holmes’ women remain domestic, operating in the personal sphere of “love,” with extremely limited agency. They appear as male adjuncts, mothers, wives, sisters, fiancées, sweethearts, and/or supporters. They may initiate a case for Holmes, their money or inheritance or problem may be its centre, but they themselves do little else. The genre exacerbates this constraint: early detective fiction focuses strongly on the puzzle aspect of cases, and even more strongly here on Holmes’ skills and idiosyncrasies. Both female and male characters, including Watson at times, become straw men to illustrate his cleverness.

Women’s agency is further limited because fifteen of the fifty-six short stories have marginal or no female characters. As early as A Study in Scarlet, Lucy Ferrier appears only in the backstory, soon a victim, abducted, forcibly married, rapidly dead. Yet her influence upon Jefferson Hope drives the novel. In eleven more stories, women are like icebergs, visible solely through effect, as in “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder,” which turns on the villain’s rejection by the suspect’s mother; “Silver Blaze,” whose villain/victim needs money for his never-seen mistress; “The Adventure of the Red Circle,” where a Mafia hit man pursues a couple because he is “in love” with the once-seen wife; and “The Adventure of the Retired Colourman,” in which the woman who caused the murders remains the villain’s nameless “wife.”

In two variants, “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place” depends on details of Lady Beatrice’s life and death, but she is dead before it starts. And in the second, “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax,” Lady Frances herself only appears as a literally silenced and stupefied female figure in a coffin.

With nominal agency, women initiate seven cases for Holmes, from Mary Sutherland in “A Case of Identity,” through Helen Stoner in “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” and Susan Cushing in “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box,” on to the landlady Mrs. Merrilow in “The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger;” but that is their last decisive action. Blurring into this group are the “helpmeets” who support an accused suspect or reveal the villain’s brutality, as in “The Adventure of Black Peter,” or laud Holmes and Watson’s exploits, as does Mary Morstan in The Sign of the Four. The other six include Miss Turner in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” Violet Westbury in “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans,” and more memorably if no more powerfully, Maud Bellamy in “The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane.”

These four groups cover forty-one stories and two novels, more than half the Holmesian oeuvre. In the remaining two novels and fifteen stories, women’s agency strengthens, and ranges from legally or morally “good” or “bad” actions to smaller and larger versions of legally bad but morally good, to both legally and morally bad and sometimes shocking, yet sometimes extenuated by the arithmetic of the case.

These variations rely on the lasting tension in detective fiction, which Conan Doyle first established, between “the law” and “justice.” While most detective story closures enforce “law,” there are always exceptions. Thus, as early as “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” we find Holmes letting a pitiful villain escape punishment on the grounds that imprisonment will only make him worse. More notably, Holmes frees the poisoner in “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot,” because the latter acted from love and most strikingly, Holmes holds a mock trial to pardon the abusive husband’s killer in “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange.” As Holmes tells Isadora Klein in “The Adventure of the Three Gables,” “I am not the law, but I represent justice …” But in extreme cases, it is not Holmes’ agency on which justice must rely.

The slightest woman with some agency beyond case-bringing is Mary Maberley in “The Three Gables,” whose sole further action is to ignore Holmes’ advice, and then have her house burgled. In contrast, the governess Violet Smith in “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist” is an independent professional woman who brings her own case, and reappears several times to help in it. Women’s independence, however, is two-edged; Holmes often praises such women, but since they threaten the domestic ideal, they must usually be feminized to survive. Thus Miss Smith is rescued with womanly cries and tears after an abduction, and more importantly, though fiercely and illegally pursued, she modestly displays no desire. Consequently, since she first appeared with mention of an “understanding” with a reputable lover, and possibly aided by her beauty, always a powerful factor for Conan Doyle, she will marry and live safely domesticated. Not all Holmes’ women fare so well.

The third and strongest woman with such agency is Violet Hunter, who initiates “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches.” Another governess, she behaves throughout with address in strong contrast to the loyal but entangled housekeeper, the complicit mother, and the passive daughter/victim. But though Miss Hunter actively assists Holmes and wins his approval, her resolve crumples before Rucastle’s threat of the gigantic mastiff, and she is so frightened she sends a wire summoning Holmes to her aid. Thus briefly feminised, she becomes a Holmesian rara avis: she completely escapes the domestic sphere, and safely eschewing all desire, lives to become a headmistress.

In five stories women who are not case-bringers show some increasingly complex agency for good; three are standard white British middle-class. Annie Harrison, fiancée of the victim in “The Adventure of the Naval Treaty,” earns Holmes’ praise for her wits and initiative, though this seems limited to a key if passive role when she foils the villain by staying as ordered in a room; she is also modest as well as engaged, and will end happily married.

More complicated is the path of Effie Munro in “The Adventure of the Yellow Face,” who married an African American and has a “little coal black negress” child she is trying to keep secret from her second husband. Revealed, she stands firmly by dead husband and living child, and her second husband gallantly accepts them both. This re-establishes her in both romantic and domestic spheres, leaving her a happy ending and Holmes to admit his one misreading of a case.

The third white British woman in this group is Ivy Douglas, in The Valley of Fear the second wife of “Birdy” Edwards, aka John Douglas, an ex-Pinkerton operative pursued to England by vengeful gangsters: she has leading agency in the plot to misrepresent the murder of his would-be assassin. The first example in this essay of women lawbreakers, she does not fare so well as Effie Munro. Since she was married and acted from love, she lives, but evidently deceiving the law exacts a heavy penalty, for her husband is mysteriously lost overboard as they flee from England.

Ethnicity affects the other two women in this group. The Peruvian Mrs. Ferguson in “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” is unwavering in her love for both her husband and her threatened child, and finds her problem with a malicious stepson happily solved, despite the origins that have cast doubt on her claims. Like Greeks, Italians, Creoles, and Russians, “Latins” were understood by Conan Doyle to be more volatile, imaginative, and lawless than the English.

In contrast, Hatty Doran in “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor” is American, and a first-generation miner’s heiress. Ethnicity and, more subtly, class, then imply she may be freer in her behaviour than an Englishwoman, but that she absconds in mid-bridal feast after wedding a British aristocrat, and lives, is due partly to her wealth, and primarily to her motive: she thought her true love was dead, but he turns up just in time for her to avoid a loveless bigamous marriage, and flee with him instead.

Two women achieve morally neutralised agency: Laura Lyons in The Hound of the Baskervilles is an actual typing-agency owner, though she relies heavily on male help, including Sir Charles Baskerville’s. She does supply important evidence, but only after learning she was romantically deceived by the villain. Her independent standing and original duplicity are negated by this turn to “the good.” That she was “wronged” also weighs to ensure her long-term safety.

Mrs. Ronder in “The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger” is more dramatic: she conspired to murder her lion-tamer husband; but her husband was a brute, her lover deserted her, she was mauled and disfigured by the lion, and is now ready to suicide. This is the first case in my discussion where a husband’s abuse neutralises a woman’s own evildoing. Holmes forestalls the (illegal) major sin of suicide by somewhat sanctimoniously persuading her that steadfast suffering can provide a powerful example for “good.” When she sends him her poison bottle as a pledge, she has reached a morally neutral and happiest end possible, and Holmes calls her a “brave woman.”

In strong contrast are the three women with unredeemed “evil” agency. Mary Holder in “The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet” appears an orthodox passive supporter of her cousin, the prime suspect for the theft of jewels from the family safe. In reality she has deceived everyone except Holmes, and at the threat of discovery she exercises independent agency, legally, but selfishly and reprehensibly, to satisfy her own desire. She elopes with the actual thief, a lord of such a wicked nature that Holmes does not bother with either law or pursuit. Her life with her accomplice, he says, will be punishment enough.

Sarah Cushing does not appear live in “The Cardboard Box,” and with doubtful objectivity her story is told by the murderer, who completely blames Sarah for his killing his wife Mary and her lover and mailing their ears by mistake to the third sister, Susan. The murders supposedly sprang from his rejection of Sarah’s openly expressed desire for him, and her subsequent alienation of Mary, which drove him back to drink and then to kill. Outright “evil” women’s agency thus is traced again to active unmarried desire, and both Mary Holder and Sarah Cushing suffer for it, the former a “fate worse than death,” the latter loss of her family, in what Holmes can only sum up as an insoluble circle of “misery and violence and fear.”

The third woman to reveal such desires is Isadora Klein in “The Three Gables.” An aristocratic widow, South American, “the celebrated beauty” with “wonderful Spanish eyes,” she is the wealthiest woman in the Holmes stories, and the most sexually active. She attracts and then destroys a young lover, then harasses his family as she attempts to steal or destroy the manuscript of his roman à clef describing the affair; yet she coaxes Holmes to “compound a felony” for her by not telling the police. So instead of facing prosecution she has merely to pay a five thousand pound “fine” to the dead lover’s mother, which is risible compensation for his life, but leaves Klein free to snare and marry a young ducal heir.

The mitigating factors in this case are, firstly, wealth and rank. In “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” these two range against each other: the jilted bridegroom is tacitly criticised for his boorish behaviour in refusing to pardon Hatty Doran’s actions; but Hatty is forgiven because she has both love and wealth. In “The Adventure of the Priory School,” wealth and rank outweigh illegality. Holmes fines the Duke for neglecting his wife, but allows his murderous illegitimate son to leave freely for Australia. In Klein’s case, adding beauty to wealth and rank can trump even unmarried, overt, evil-doing women’s desire, and make Holmes himself complicit in her pardon.

In a further seven stories, women with agency personally break the law, but for a “good” end. Interestingly, this group is ethnically the most diverse. The heiress Sophy Kratides in “The Greek Interpreter” appears only once, but a newspaper cutting implies that she killed or had her abductors killed after the story’s end. This vengeful and illegal agency is morally softened by the wrongs she suffers, and tacitly, by her ethnicity. Similarly, “Miss Burnet,” the purported governess in “The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge,” is the widowed Señora Durando of “San Pedro” in South America, who betrays the villain to would-be assassins to avenge her murdered husband. Here, more orthodoxly, women’s illegal agency is justified by faithful prior love and marriage. Similarly, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, the housekeeper Mrs. Barrymore is pardoned because familial love drives her to shield her escaped convict brother, while Beryl Stapleton proves an unwilling accomplice in her husband’s villainy; hence her own double-dealing in allowing Sir Henry to think her single is remitted.

The German woman Elise in “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb” attempts to warn and then does rescue the engineer trapped in a massive mechanical press by the villainous counterfeiters, but without love to tip the scales, her complicity in their crime allows only a disappearance into obscurity, without further notice or praise.

In “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez,” the arithmetic is more complex. The Russian Anna does actual if accidental murder while trying to burgle her villainous husband’s study for papers that would get her true love released from Siberia. This motive ensures that, after she is unmasked but conveniently suicides, Holmes can declare that he will take the papers to the Russian ambassador,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Nisi Shawl

- Introduction by Tamara R. Bower and Resa Haile

- I. Are Women Persons in the Victorian Era?

- II. Examining Female Characters’ Need and Capacity for Subterfuge

- III. An Interlude

- IV. Restrictions and Allowances for Women in the Most Important Matters: Love and Marriage

- V. An Examination of Women’s Ability for Choice and Control in Crisis

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Index