eBook - ePub

The Generic Challenge

Understanding Patents, FDA and Pharmaceutical Life-Cycle Management (Sixth Edition)

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Generic Challenge

Understanding Patents, FDA and Pharmaceutical Life-Cycle Management (Sixth Edition)

About this book

This Sixth Edition of The Generic Challenge provides important new updates on current regulatory, legal and commercial issues affecting brand and generic pharmaceutical products, including new laws establishing generics for biologics, and changes brought

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter | 1 |

Overview of Patents

The invention all admired,

and each, how he

To be the inventor missed,

so easy it seemed

Once found, which yet unfound

most would have

thought impossible.

John Milton

Paradise Lost

“Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

Thomas A. Edison

ORIGINS OF U.S. PATENTS

Patents have been around longer than you may think. Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. constitution provides that

“Congress shall have the Power … to promote the Progress of Science and Useful Arts by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

As an interesting historical tidbit, President George Washington signed the first patent bill in 1790 which laid the foundations of the modern American patent system. The U.S. patent system was unique; for the first time in history the right of an inventor to profit from his invention was recognized by law. Previously, privileges granted to an inventor were dependent upon the prerogative of a monarch or upon a special act of a legislature.

In that same year, one Samuel Hopkins of Pittsford, Vermont, was granted the first U.S. patent on an improved method of making potash. The reviewer of this patent was none other than Thomas Jefferson, the then Secretary of State. Jefferson granted the patent after obtaining signatures from the Attorney General and from President Washington. Well, enough history.

Is a Patent a Legal Monopoly?

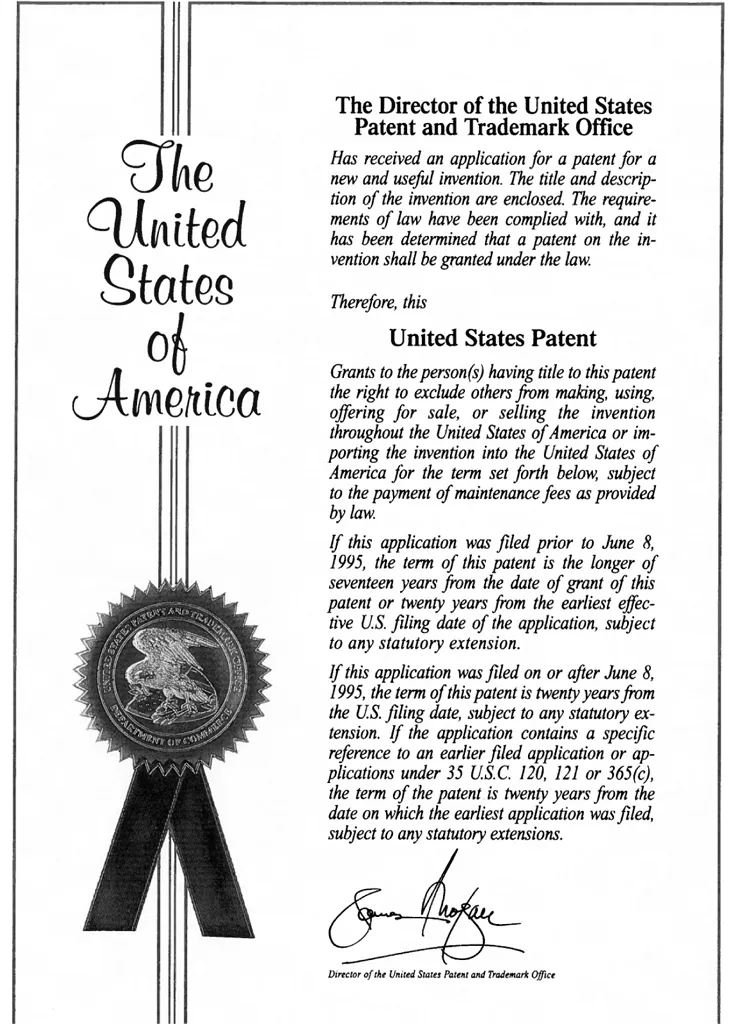

Classically, a patent is often described as a legal monopoly. We will find later that this description of a patent is not so accurate. Technically, a patent is a governmental grant that provides the holder for a limited period of time the exclusive right to prevent others from making, using or selling the patented product or process in exchange for his disclosure of the invention to the public. The careful reader will note we did not say the patent granted the owner the right to make, use or sell the invention. That basic distinction is a hard one to understand and will be discussed further. Patents are also intended to benefit the public, as they encourage less secrecy, so that important information is not lost when its owner dies, and to provide a means to encourage capital formation and investment in new ideas resulting in new industries, jobs, etc.

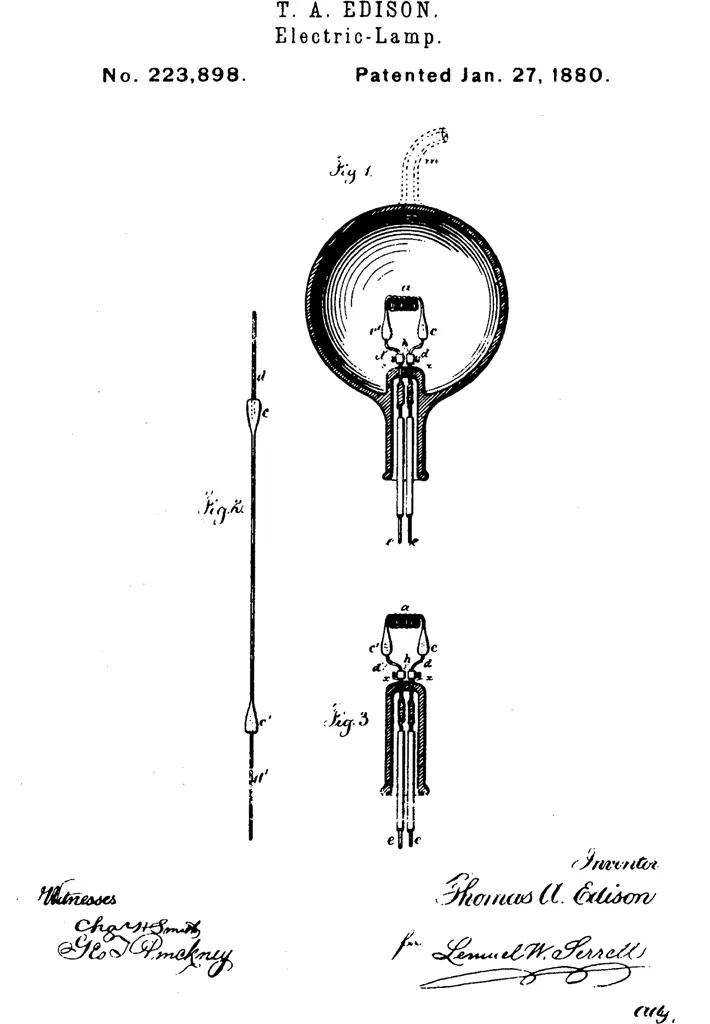

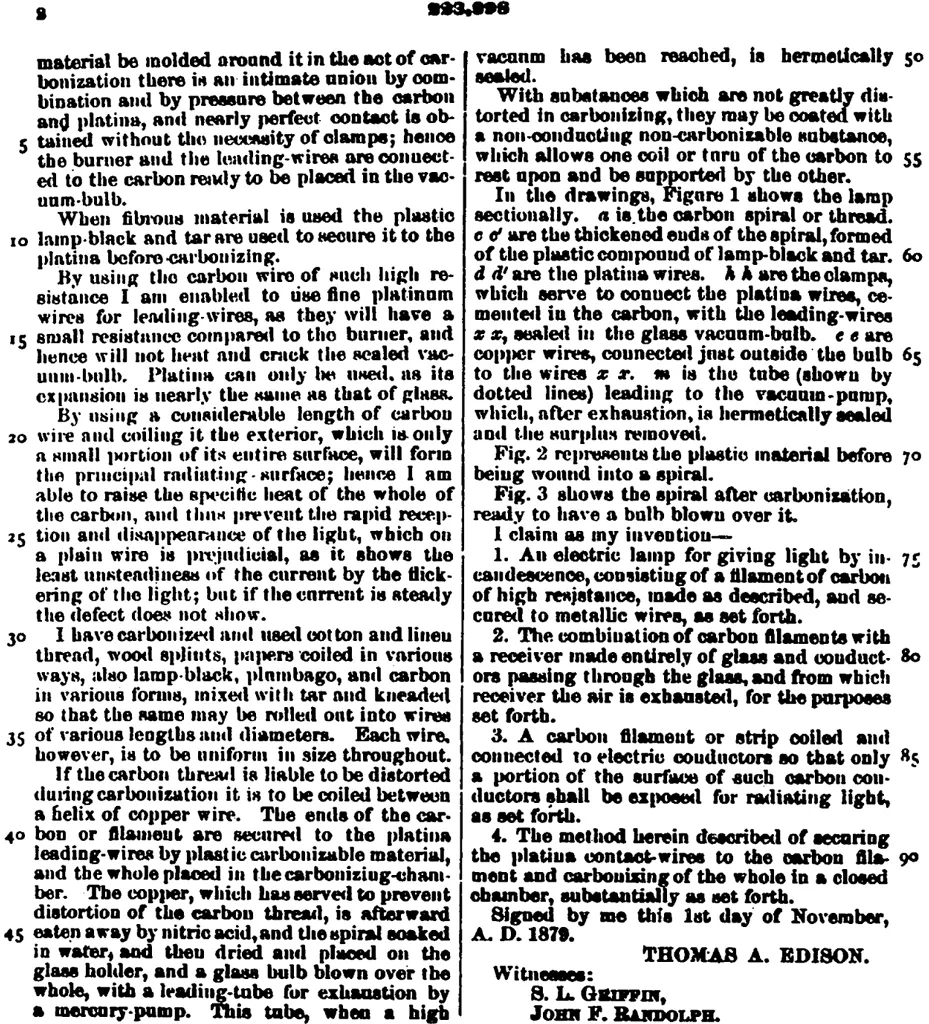

Edison Patent for the Electric Light Bulb

Probably the most famous invention of all is the Edison patent for the electric light bulb shown on the following page, along with a standard front cover of a U.S. patent. Not only has the invention lasted for well over a hundred years, but the electric light bulb has become the icon for invention itself! Edison was a prolific inventor and during his lifetime he amassed a record 1093 patents: 389 for electric light and power, 195 for the phonograph, 150 for the telegraph, 141 for batteries and 34 for the telephone.

You will notice the Edison patent is fairly short, consisting of only a few pages and only four claims. These days, patents tend to be longer, some running to hundreds of pages and often including hundreds of claims, but brevity, as in some other forms of human communication, can often be wiser, and in any case less expensive, as patent lawyers are usually paid by the hour.

What is a Product or Process?

So now we know a patent is a time-limited right to exclude others from making, using or selling a product or process. So what is a “product” or “process”? The U.S. Supreme Court has broadly interpreted it as “anything under the sun made by man” when they agreed that the first man-made bacteria engineered to eat oil could be patented. More specifically, a “product” can be a medical device such as an artificial heart or a composition of matter, such as a new chemical compound or biologic agent, such as a vaccine, or formulation for a drug product or anything manufactured including a mouse genetically engineered to get cancer. A typical pharmaceutical product would consist of a patented chemical, known as a new chemical entity (NCE) and a patentable new formulation, such as an oral or topical dosage form, for delivery of the new chemical entity to the body.

1. Cover page of a U.S. Patent

2. Edison’s Electric Light patent

A “process” as applied to pharmaceutical products is a method of treatment of persons or materials to produce a given result. Included in patentable processes are methods of manufacturing a new chemical entity or a new method of manufacturing a known compound. A process is also a method of treating a condition or disease with either a new drug (first medical use) or an old drug that was previously known for treating a different condition or disease (second medical use).

A Patent is a Sword, Not a Shield!

The next sentence is the most important thing to know about patents. A patent is a sword, not a shield! That is, a patent is primarily an offensive weapon that allows its owner, by enforcement of the patent, to prevent others from making the patented item or using or selling the patented method during the life of the patent. However, the patent has little or no defensive character and thus it cannot protect you from being sued for infringement under someone else’s patent. Most people find this concept the most difficult one to understand. If I have a patent on my gizmo, how can I be sued for patent infringement? The answer is simple. A patent is a sword, not a shield. As mentioned earlier, a patent does not grant its owner the right to do anything. Instead, it grants the owner the right to prevent others from doing something.

The following example may help explain this counter-intuitive concept. If I owned the patent for the first carburetor, which I designed to have two barrels, and later you improved my carburetor and obtained a patent on the first 4-barrel carburetor, what happens? I can keep your 4-barrel carburetor off the market with my general patent covering carburetors, but you can prevent me from selling your 4-barrel version of my carburetor with your patent. So if we both want to sell 4-barrel carburetors, we must cross-license our patents to each other or neither of us can make or sell them. My broad carburetor patent does not shield me from your 4-barrel carburetor improvement patent and your improvement patent does not give you any rights to make or sell your improvement.

Note that this dynamic system encourages others to make improvements of your invention so they can potentially negotiate entrance into the market. This technique of patenting improvements is practiced to the point of frustration in Japan where obtaining a patent can take 5–10 years and by the time the originator has patented the basic concept, there may be 20 patents in the hands of others covering a myriad of minor improvements. As a result, the patented article is difficult to make without running into one of the improvement patents thus forcing a cross-license.

BASIC TERM OF A PATENT

In the U.S., patents used to have a term of 17 years from the date the patent was granted. This was set in stone. There were some exceptions, such as a shorter term where Patent Office rules require a patent owner to voluntarily agree to shorten his patent life in order to obtain the patent, but in general the rule was 17 years from date of grant. That was fair because if your patent application were held up in the Patent Office by government red tape, you would still get your 17 years once it was finally granted.

The rest of the world, on the other hand, gives 20 years from the date of filing the patent. This can allow quite a bit of mischief since it may take years to get the patent granted and any time lost is just hard luck for the patent owner. And competitors are happy to assist in any delays at the Patent Office through oppositions and other such procedures that allow competitors to challenge the grant of a patent. As a result it typically takes five to ten years to get a patent fully and finally granted in Europe and Japan, compared to only one to three years in the U.S.

However, that has also recently changed, as the U.S. now also provides for oppositions after grant called Post Grant Review (PGR), where competitors can challenge the validity of your patent within nine months after grant in the Patent Office, on patent applications filed on or after March 16, 2013, as discussed later in this chapter.

Harmonization

Then along came harmonization, a catchy word, but one that can lead to trouble. In the interests of harmonization, the U.S. agreed to match the other countries’ rules so, effective June 8, 1995, any patents filed on or after that date had a life of 20 years from date of filing. Patents filed before that date got the longer of the two ways to compute their life (if only we all had that choice).

There was one catch and that was that the filing date the term of the patent was based on was the earliest effective filing date for the patent. This is because patent holders in the U.S. can file follow-on patent applications based entirely (continuations) or in part (continuations-in-part) on the former patent application and get the benefit of the date of filing of the first-filed patent application for all common subject matter. If you file a string of patent applications as continuation (CON) applications or continuations-in-part (CIP) applications, the patent life for the last patent in the string is based on the filing date of the first patent application.

Typically, a patent attorney will use a continuation application to try to get claims granted in a follow-on patent application when time for prosecution before the Patent Office has run out on the originally filed application or when only some of the claims he or she wanted were granted in the originally filed application (thus a second bite at the apple). A continuation-in-part application is typically used to add something to an already existing application, such as a new preferred formulation or some additional examples of compounds that were not disclosed in the original application.

Also in the interests of harmonization, the U.S. joined the international community in publishing patent applications 18 months after they are filed, unless you ask not to be published and agree not to file the patent outside the U.S. If you recall the beginning of the chapter where the granting of a patent was a reward for disclosure of the invention, there seems something basically wrong with forcing the disclosure of the invention without first granting the patent! But that is now the law and the only way to get around it is to agree not to file abroad.

Submarine Patents

These new rules also solved a problem that had been invented by a man named Lemelson. Lemelson filed numerous patent applications in the 1950s on a variety of forward-thinking concepts and then he did an unusual thing. Instead of being in a hurry to get his patents granted, he took his time and re-filed the applications as continuation applications and kept adding subtle refinements to the claims and kept doing so for 40 years until, in the early 1990s when he finally allowed his patents to be granted, they covered important modern inventions. Since his patents were based on the old rules, he got a 17-year life from the date of grant.

After his patents were granted, he asked just about every company in the U.S. for royalties and got them after suing many. He collected over a billion dollars in royalties. His inventions ranged from Hot Wheels track to bar coding (the black and white bars and numbers on just about every box of something sold today), and his patents covered something that just about every commercial enterprise did. He may have had more patents than Edison, but unlike Edison, he never actually made or perfected any of these inventions himself.

This kind of patent jokingly became known as a “submarine” patent because it stayed hidden under the surface for a long time and then arose and blasted you out of the water when you least expected it. That was because at the time, patent applications were kept secret in the U.S. until they were granted and Lemelson never filed his patents outside the U.S. where they would be published. By making the date of a patent based on its earliest effective filing date instead of its grant date, and by publishing pending patent applications, it essentially ended new submarine patents starting June 8, 1995.

And while the courts of justice grind slow, they grind fine. In Symbol Technology v. Lemelson (Fed. Cir. 2005), the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which handles all patent appeals from the Federal District Courts, ruled that Lemelson’s patents were unenforceable because of the way he got them, namely by intentional delay or as the courts have been calling it “late claiming”. This undoubtedly caused his successors to suffer some heartburn at their Aspen ski lodges, but presumably not Mr. Lemelson, as he is likely too busy filing further continuing applications in the heavenly Patent Office.

So to recap, in the U.S., a patent having a filing date on or after June 8, 1995 has a term of 20 years from its earliest effective filing date. Patents filed before June 8, 1995 have a term which is the longer of 20 years from its earliest effective filing date or 17 years from its date of issue. In the rest of the world, patents typically last 20 years from their filing dates. In Japan, patents are also granted for 20 years from their filing dates, but not longer than 15 years from their grant date.

Patent Term Adjustments and Extensions

There are also complicated Patent Office rules which provide for patent term adjust...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Preface to the Sixth Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Overview of Patents

- Chapter 2 Patent Enforcement and Infringement

- Chapter 3 Pharmaceutical, Biologic and Medical Device Patents

- Chapter 4 Overview of FDA

- Chapter 5 Exclusivity for Brand Name Innovative Drug Products

- Chapter 6 Generic Drugs: Hatch Waxman Act

- Chapter 7 Generics for Biologic Drugs

- Chapter 8 Putting it All Together: Product Life-Cycle Management

- Chapter 9 Conclusions and Final Thoughts

- Glossary of Terms

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Generic Challenge by Martin A. Voet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Intellectual Property Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.