![]()

PART I

Crisis

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Baseline

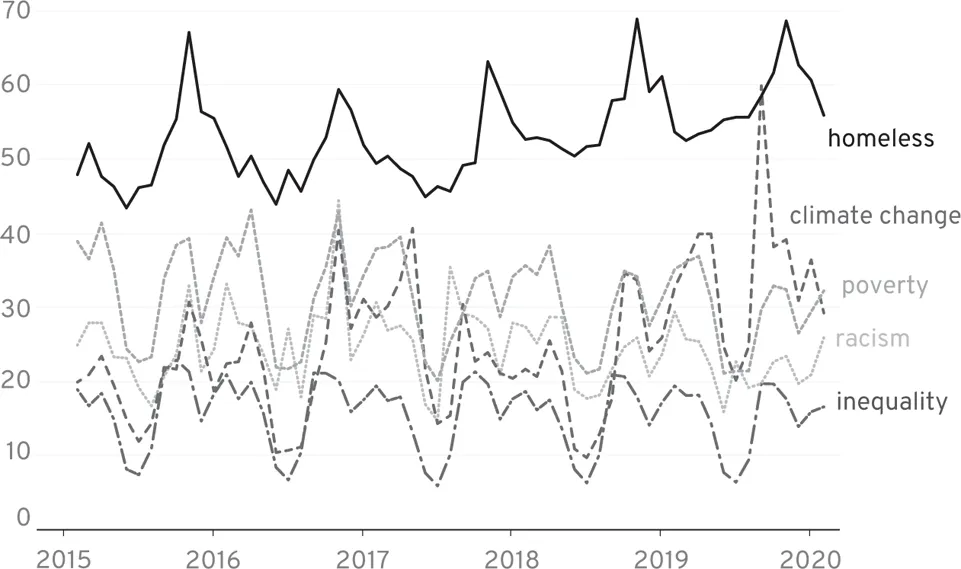

Homelessness occupies a prominent place in American political life. Although less than one-fifth of 1 percent of the U.S. population experiences homelessness on a given night in the country, the issue receives considerable attention from policy makers and the general public. This spotlight is striking given the scale of the homelessness crisis when compared to other prominent social problems. That fifth-of-a-percent figure translates to about five hundred sixty-eight thousand people. To be sure, this number should feel large and unacceptable. But on an absolute basis, for example, homelessness pales in comparison to the nation’s poverty crisis: Over thirty-four million Americans were living below the federal poverty line in 2019. Meanwhile, abundant evidence highlights the political preoccupation with homelessness. In 2020, a poll in Washington State revealed that voters ranked homelessness as the top priority for the state legislature—far above other common public concerns like transportation, the economy, the environment, and health care.1 We observe a similar focus at the national level. As depicted in Figure 1, from January 2015 to January 2020, more people in the United States searched for the term homeless via Google than for inequality, racism, poverty, and climate change.2

Figure 1. Public interest over time for five search terms. Data source: Google Trends

How might we explain this seemingly disproportionate interest in the issue of homelessness? Two potential explanations come immediately to mind. First, maybe this interest isn’t as disproportionate as it might initially appear. That is, maybe the numbers are wrong. Among astute observers, it is well understood that official point-in-time census estimates of homelessness underestimate the true size of the population experiencing homelessness on any given night.3 For example, the federal definition excludes many precariously housed individuals and families who might be living with a friend or temporarily living in a motel room. The more expansive definition of homelessness used by the U.S. Department of Education suggests a population of 1.35 million homeless students without counting their parents.4 Furthermore, across greater spans of time—say, lifetimes—roughly 5 percent of the population experiences homelessness at least once.5 In light of these figures, it is more accurate to consider homelessness as a problem that affects millions, rather than hundreds of thousands. But even the larger figure highlights the fact that only a small fraction of people living in poverty actually lose their housing.

More fundamentally, though, a second explanation for the intense interest in the topic may stem from the simple incongruity of a half million people living in shelters and on the street in the wealthiest country in the world. Reactions to this apparent paradox are diverse. For some, homelessness is a moral and political outrage indicting the capitalist system on which U.S. society is based; for others, homelessness is a scourge ruining the nation’s largest and most dynamic cities. Other observers reside somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. What is uncontroversial is that homelessness elicits strong and emotional responses from all corners of society. From the perspective of the public, the intense focus on homelessness requires—and demands—an explanation. There is a strong desire to understand the causes of homelessness and where to assign blame. This book is in part concerned with the question of blame.

In January 2020, just weeks before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States, a long-simmering debate about the origins of and responsibility for the homelessness crisis erupted in public. Members of the federal government, including President Trump, argued vocally that the high rates of homelessness in many U.S. cities were a function of the local failings of Democratic leadership and policies. Referencing Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the president said, “She ought to go home and take care of her District, where the homeless is all over the place, and the tents and the filth and the garbage is eroding right into the Pacific Ocean and into their beaches.”6 In response to this finger-pointing, state and local policy makers—most notably California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, a Democrat—argued that a lack of federal assistance had starved local communities of sorely needed resources, and housing instability and homelessness had flourished in turn.

Certainly, some of this political jostling is a product of the polarized nature of U.S. politics in the 2020s. From voting rights to climate change—issues that would appear at face value to be resoundingly nonpartisan but which often provoke party-line votes—policy responses to (and public perception of) the issues of our time are characterized by tribalism. Tailored media narratives and the so-called filter bubbles of social media add fuel to the flame of confirmation bias. It’s harder than it should be to find fact-checked information, and it’s even harder to internalize narratives that run counter to our beliefs. In this respect, homelessness is no different: It tends to provoke hyper-partisan diagnoses and prescriptions. And as with most cases of hyper-partisanship, neither argument above—Trump’s nor Newsom’s—sufficiently explains the state of homelessness in the country. If inadequate federal support alone accounts for the crisis, why does the rate of homelessness vary so substantially across cities? Presumably, all cities would be equally starved of resources if federal retrenchment were the cause. Yet while some cities have seen rates of homelessness rise over the last ten years, many others have seen rates fall. And if Democratic mayors and governors are the problem, how can we account for the many cities and states with both Democratic leadership and policies and relatively low rates of homelessness? Unsurprisingly, the polarized plotlines are too simple, but they draw attention to essential questions about the nature and causes of the homelessness crisis.

As Ezra Klein writes in his recent book Why We’re Polarized, one of the other phenomena driving polarization in the country is a grafting of our political identities onto national (as opposed to local) politics.7 National politics, by definition, require a flattening of local variation—and in our de facto two-party system, with this flattening often comes a false dichotomization of many complex issues. This complicates the effort to respond to local issues that vary by geography—homelessness among them. In the United States, one of the most pressing and vexing questions about homelessness concerns the substantial variation in per capita rates of homelessness in cities across the country. Seattle and San Francisco, for example, have roughly four to five times the per capita homeless population of Chicago.8 The stark differences between seemingly vibrant and healthy cities invite us (and many others) to ask: Why is homelessness so bad in cities like Seattle and San Francisco? Is this a failure of individuals, politicians, markets, or other structural forces? An understanding of variation might help us unlock the drivers of this crisis.

Many of us have, for good reason, struggled to identify a credible explanation for this variation. Accounts of and references to homelessness on television, online, in newspapers, and in scholarly sources offer a long list of potential causes of the issue; among them addiction, mental illness, poverty, domestic violence, eviction, high housing costs, racial discrimination, unemployment, and many others. Reports based on interviews with people experiencing homelessness highlight a wide range of potential causes, as well. A recent report from Seattle/King County for example, noted the following self-reported causes of homelessness among respondents to the annual point-in-time homelessness census: job loss (24 percent of respondents), alcohol or drug use (16 percent), eviction (15 percent), divorce or separation (9 percent), rent increase (8 percent), argument with family or friend (7 percent), incarceration (6 percent), and family/domestic violence (6 percent).9 Confronted with the question of why some cities have far greater per capita rates of homelessness than others, a reasonable, logical reaction might be to assume that higher levels of homelessness stem from higher incidences of these self-reported causal factors in these cities. In this book, we examine this logic.

While perusing any list of potential causes of homelessness, one can generally break the ostensible explanations down into two overarching categories. Some causes are individual in nature, and some are structural. The bifurcation is consistent with decades of research on poverty and homelessness. On one side of the debate are those who argue that poverty and homelessness are the result of individual factors, that vulnerabilities related to housing instability are fueled by illness, mental condition, laziness, or poor decision-making, including—for these observers—excessive drug and alcohol use. And in the central downtowns of cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, or Seattle, thousands of unsheltered people experiencing homelessness may indeed be suffering from a substance use disorder, mentally ill, and/or unemployed. Following this logic, it is the disproportionate presence of people with these vulnerabilities in certain cities that explains the substantial variation in per capita homelessness rates around the country. Whether born in or attracted to these cities, people comprise the homelessness crisis, and so homelessness is an individual problem. (It is not uncommon for some to argue that homelessness is exclusively an individual choice.) On the other side of the debate are those who argue that larger, structural forces, such as market conditions, housing costs, racism, discrimination, and inequality, causally explain the prevalence of homelessness. Under the structural explanation, homelessness is a consequence of broader and deeper societal factors driving people at the margins of society out of their housing.

Perhaps there is a middle road. The individual explanation is alluring—it’s individual people who lose their housing, after all. Surely there must be systematic factors at play, though; otherwise, how could we possibly account for the dramatically different rates of homelessness around the country? Even if you were entirely convinced of the individual explanation, you would have to acknowledge that some kind of systemic variation—some combination of environmental, political, economic, and demographic trends—characterizes different places. In 2019, less than 1 in 1,000 residents were unhoused in Alabama and Mississippi, while California and Oregon had over five times that rate. Why? Existing research provides a helpful roadmap to navigate the seemingly complex and, at times, contradictory evidence about the causal drivers of homelessness. Homelessness researcher Brendan O’Flaherty, for example, suggests that to generate causal explanations of homelessness, one must consider the interaction between individual characteristics and the context in which that person resides. Either explanation alone is insufficient to explain or predict individual homelessness. By extension, he argues that people who lose their housing are effectively the wrong people in the wrong place.10 This frame helps to provide a vantage point from which to consider the central question of this book: What explains the substantial regional variation in per capita homelessness rates in the United States?

To cut to the chase, the answer is on the cover of this book: Homelessness Is a Housing Problem. Regional variation in rates of homelessness can be explained by the costs and availability of housing. Housing market conditions explain why Seattle has four times the per capita homelessness of Cincinnati. Housing market conditions explain why high-poverty cities like Detroit and Cleveland have low rates of homelessness. Housing market conditions also explain why some growing cities, like Charlotte, North Carolina, are not characterized by the levels of homelessness that coastal boomtowns like Boston, Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco are. Variation in rates of homelessness is not driven by more of “those people” residing in one city than another. People with a variety of health and economic vulnerabilities live in every city and county in our sample; the difference is the local context in which they live. High rental costs and low vacancy rates create a challenging market for many residents in a city, and those challenges are compounded for people with low incomes and/or physical or mental health concerns.

• • •

According to estimates from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), at least 567,715 people experienced homelessness on a single night in 2019.11 But this aggregate figure masks significant geographic variation in the distribution of per capita homelessness across the country. The metropolitan areas of New York, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston alone account for over 29 percent of the homeless population in the country, despite being home to only about 7 percent of the general population. Regardless of one’s view of the problem—and the political lens through which one considers homelessness—it is reasonable to wonder what it is about these cities that produces (or, according to some, attracts) such large and disproportionate populations of people experiencing homelessness. To explore this phenomenon, we shift the unit of analysis away from the individual and turn our attention to the metropolitan area. From this perspective, we are not interested in predicting whether a given person will experience homelessness or why someone lost their housing in the past; we are interested in understanding why, for example, the crisis is so much more extreme in Boston than in Cleveland. This analytic pivot does not preclude individual explanations fo...