- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of Smithsonian Magazine's Favorite Books of 2022

With wildlife thriving in cities, we have the opportunity to create vibrant urban ecosystems that serve both people and animals.

The Accidental Ecosystem tells the story of how cities across the United States went from having little wildlife to filling, dramatically and unexpectedly, with wild creatures. Today, many of these cities have more large and charismatic wild animals living in them than at any time in at least the past 150 years. Why have so many cities—the most artificial and human-dominated of all Earth’s ecosystems—grown rich with wildlife, even as wildlife has declined in most of the rest of the world? And what does this paradox mean for people, wildlife, and nature on our increasingly urban planet?

The Accidental Ecosystem is the first book to explain this phenomenon from a deep historical perspective, and its focus includes a broad range of species and cities. Cities covered include New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Austin, Miami, Chicago, Seattle, San Diego, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Digging into the natural history of cities and unpacking our conception of what it means to be wild, this book provides fascinating context for why animals are thriving more in cities than outside of them. Author Peter S. Alagona argues that the proliferation of animals in cities is largely the unintended result of human decisions that were made for reasons having little to do with the wild creatures themselves. Considering what it means to live in diverse, multispecies communities and exploring how human and nonhuman members of communities might thrive together, Alagona goes beyond the tension between those who embrace the surge in urban wildlife and those who think of animals as invasive or as public safety hazards. The Accidental Ecosystem calls on readers to reimagine interspecies coexistence in shared habitats, as well as policies that are based on just, humane, and sustainable approaches.

With wildlife thriving in cities, we have the opportunity to create vibrant urban ecosystems that serve both people and animals.

The Accidental Ecosystem tells the story of how cities across the United States went from having little wildlife to filling, dramatically and unexpectedly, with wild creatures. Today, many of these cities have more large and charismatic wild animals living in them than at any time in at least the past 150 years. Why have so many cities—the most artificial and human-dominated of all Earth’s ecosystems—grown rich with wildlife, even as wildlife has declined in most of the rest of the world? And what does this paradox mean for people, wildlife, and nature on our increasingly urban planet?

The Accidental Ecosystem is the first book to explain this phenomenon from a deep historical perspective, and its focus includes a broad range of species and cities. Cities covered include New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Austin, Miami, Chicago, Seattle, San Diego, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Digging into the natural history of cities and unpacking our conception of what it means to be wild, this book provides fascinating context for why animals are thriving more in cities than outside of them. Author Peter S. Alagona argues that the proliferation of animals in cities is largely the unintended result of human decisions that were made for reasons having little to do with the wild creatures themselves. Considering what it means to live in diverse, multispecies communities and exploring how human and nonhuman members of communities might thrive together, Alagona goes beyond the tension between those who embrace the surge in urban wildlife and those who think of animals as invasive or as public safety hazards. The Accidental Ecosystem calls on readers to reimagine interspecies coexistence in shared habitats, as well as policies that are based on just, humane, and sustainable approaches.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Accidental Ecosystem by Peter S. Alagona in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Hot Spots

Ecologists love nature reserves: places where people are visitors, wild animals roam free, and ecosystems still seem, at least on the surface, relatively intact. Yet, in an era when humans are transforming almost every aspect of the natural world, such places are increasingly the exception, not the rule. For a different way to understand wildlife in the twenty-first century, you don’t need to travel to some distant mountain range or remote wilderness area. Instead, take a free, twenty-five-minute ride on the Staten Island Ferry.

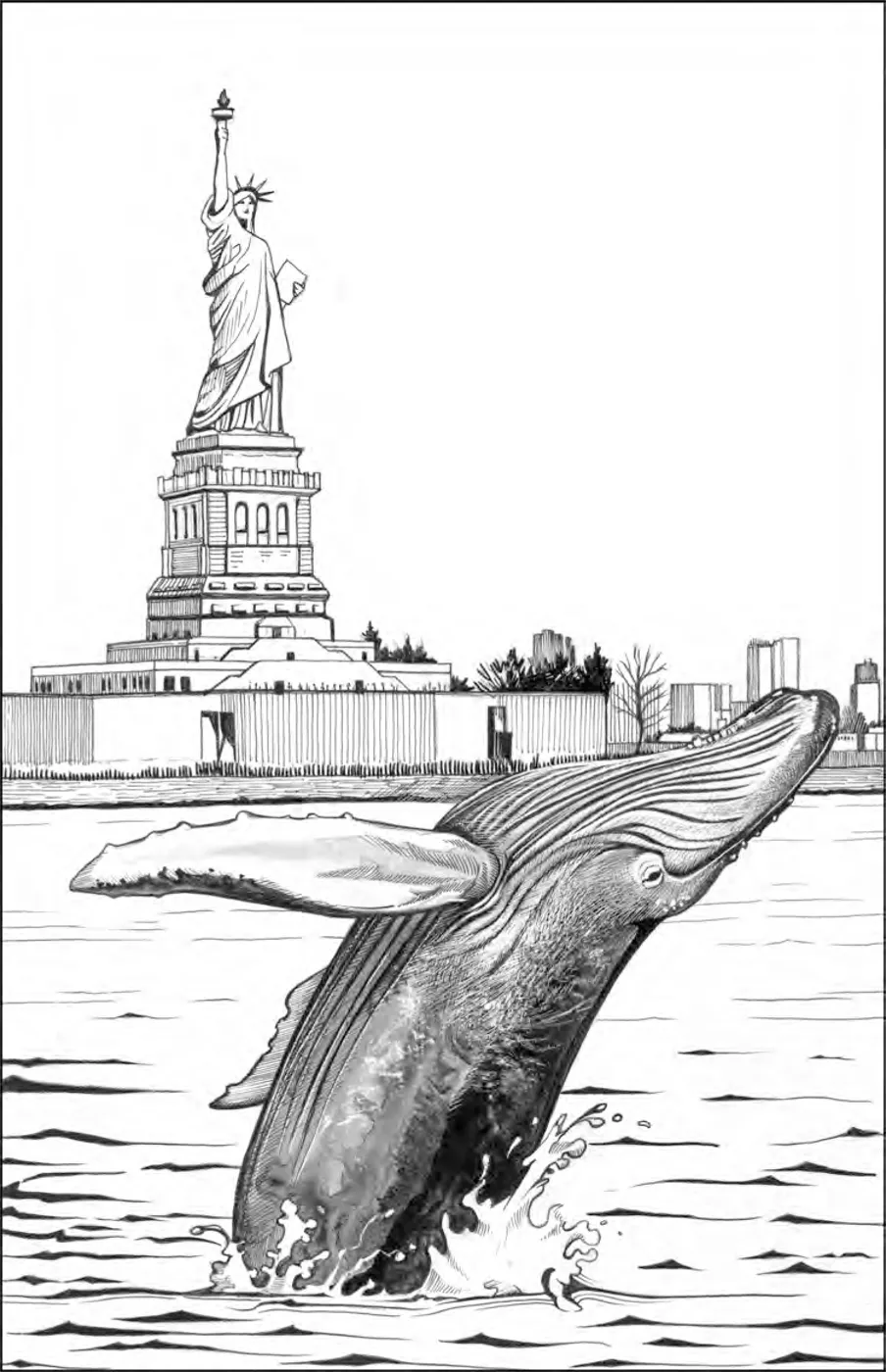

Heading south from the Whitehall Terminal in lower Manhattan, the ferry plies some of the most urban waters on our planet. To the north loom the Financial District’s skyscrapers, including the fraught monolith of One World Trade Center. To the west stand the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. To the east sit the partly artificial landmass of Governors Island and beyond it the Port of New York and New Jersey’s giant Red Hook shipping terminal.

Look closer, though, at the leafy hills of Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery, or out past the Verrazano-Narrows toward Lower Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, and you will see the traces of a once-great ecosystem. Look even closer—down into the milky blue waves for the humpback whales and harbor seals that, in recent years, have returned to these waters after long absences, or upward at the gulls, terns, and ospreys circling in the sky overhead—and you may catch glimpses of its partial return (see figure 1).

Prior to European contact, the place we now call New York City teemed with life. The island of Manhattan alone, according to the ecologist and author Eric Sanderson, contained an estimated fifty-five distinct ecological communities, more than a typical coral reef or rain forest of equivalent size. Its meadows, marshes, ponds, streams, forests, and shorelines housed between 600 and 1,000 plant species and between 350 and 650 vertebrate animal species.1

Early visitors and settlers marveled at New York’s wildlife. David Pieterz de Vries, writing around 1633, counted “foxes in abundance, multitudes of wolves, wild cats, squirrels—black as pitch, and gray, flying squirrels—beavers in great numbers, minks, otters, polecats, bears, many kinds of fur-bearing animals.” Others complained of chirping birds and croaking frogs so loud that it was “difficult for a man to make himself heard.” Yet this racket was a mere inconvenience. According to the seventeenth-century politician and businessman Daniel Denton, New York’s rich land and temperate climate ensured the “Health both of Man and Beast.”2

Compare colonial New York to Americans’ current benchmark for wild nature, Yellowstone National Park. Congress established Yellowstone, the world’s first national park, in 1872, to protect its scenery and wildlife and to attract tourists to an area that, unlike New York, had few other economic prospects. Yellowstone is now a United Nations Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site. Drawing more than four million visitors annually (roughly the same number of people who live in Manhattan and Brooklyn combined), it is one of America’s greatest wilderness wonderlands. It is also one of the few areas in the Lower 48 US states that retain their full suite of native fauna—from wolverines, grizzly bears, and lynx to bighorn sheep, mountain goats, elk, moose, pronghorn, and bison.

Yellowstone may be a paradise for ecologists—since 1970, it has accounted for more than one-third of all the published peer-reviewed articles based on research conducted in the national parks—but it is no picnic for most of the creatures that actually live there.3 With its frigid winters, short growing seasons, and rocky, acidic, nutrient-poor soils, the park can be a tough place to live—especially compared to the rich, temperate, and sheltered landscapes and waterways that once defined the area we now know as New York City. Prior to the nineteenth century, almost all of the big wild species in Yellowstone also inhabited places that were wetter, milder, more productive, and richer in resources. In such areas, these creatures often had larger populations and required smaller home ranges to meet their needs. Most of them remain in the park today not because it is their ideal habitat but because people have protected it and because they have few other places to go. Yellowstone remains a land of immense natural value. Yet it is so important not because nature endowed it with biological diversity but rather because people chose to protect it.

The numbers say it all. Prior to European contact, Manhattan, an island of just twenty-three square miles, contained roughly the same number of species as now live in Yellowstone National Park, a vast region of mountains, valleys, forests, and prairies covering some thirty-five hundred square miles. This means that the Manhattan of yesteryear housed around 150 times more plant and animal species per land area than the Yellowstone of today. If European settlers had wanted to save North America’s wildlife instead of getting rich from harvesting it, they would have built a great city in northwest Wyoming and set up a national park at the mouth of the Hudson River.

There are several reasons why New York contained such a riot of life. For two and a half million years, glaciers sheared its cliffs, rounded its hills, tilled its soils, and polished its bedrock, leaving a varied landscape. Located at the boundary between the mid-Atlantic region and New England, it was a biological crossroads where northern and southern species overlapped and mingled. It also straddled contrasting habitats, in a place where salt water met freshwater and land met sea. Nutrient-rich runoff from the Adirondack Mountains flowed into a vast estuary where it circulated with the tides, fertilizing plants and feeding animals while supplying sediment for mud flats, wetlands, and beaches.4

Humans also had a crucial role to play. For thousands of years, the Lenape people and their predecessors hunted, gathered, and fished in the area. They stewarded and shaped the land, setting fires to clear brush, stimulate plant growth, and create wildlife habitat, while moving seasonally to harvest resources and find shelter. Archaeologists used to think that the coastal Lenape, like their inland Algonquian relatives, relied on staple crops such as squash and maize. Yet more recent work suggests that, in the area that became New York City, natural resources were so abundant that the prosperous locals had little need for crops. Though gardens were common, they supplied less than 20 percent of the calories people consumed. The rest came from their ecosystem.5

The Dutch, who arrived in New York in 1609 and settled in 1624, also found the area to their liking. With its timber for shipbuilding, fish for catching, furs for trapping, and whales for harvesting just offshore, it contained the raw materials to fuel an early modern capitalist economy. These settlers quickly grasped that the area’s central location, inland river access, and deepwater port could make it an ideal site for gathering resources and trading with indigenous and European partners. New York soon emerged as a center of North American and trans-Atlantic commerce. By the time of the first U.S. census, in 1790, it had become America’s most populous city.

• • • • •

New York may seem exceptional (New Yorkers certainly think so), but it is far from unique in its ecological richness. Many of the biggest cities in the United States are located on sites that, prior to their founding, were unusually biologically diverse and productive compared with their surrounding regions. They were also crawling with wildlife.

Several factors explain this pattern of overlapping ecological richness and urban growth. Some cities emerged on the sites of indigenous settlements that were well positioned to access food, water, and other resources. In California, for example, beginning in 1769, Spanish-speaking priests, soldiers, and bureaucrats established a chain of missions along the coast and in nearby valleys. These colonial outposts were built next to indigenous communities, which benefited from their sites’ agreeable climates, diverse fish and game, staple food plants such as oaks, and year-round access to freshwater, a rarity in much of that arid region. After Mexico achieved independence in 1821, pueblos formed around the old missions, later becoming farming towns and eventually cities. California’s four biggest cities—Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and San Jose—all share these indigenous, mission, and pueblo roots.

Los Angeles deserves special mention because of its well-documented ecological history. When the padres founded their missions at San Gabriel and San Fernando, they had no idea that just fifteen miles away and a century later, farmers, oil workers, and eventually paleontologists would discover one of the world’s greatest troves of fossils, covering the past fifty thousand years. Formed from the same deposits that fueled Southern California’s early twentieth-century oil boom, the La Brea “Tar Pits” have produced more than three million fossils, including the remains of around two hundred vertebrate animal species. A list of the entombed includes extinct behemoths like Columbian mammoths and giant short-faced bears, as well as current stalwarts like skunks and coyotes. These creatures were there for a reason. The Los Angeles Basin offered a mild climate and diverse habitats that supported a spectacular profusion of wildlife. Even after most of the basin’s megafauna disappeared, by the end of the last ice age, it remained a kind of American Serengeti. Los Angeles, like New York, was a hotspot of biological diversity.

Even where indigenous communities were small or absent, American cities tended to develop in areas that provided settlers with easy access to rich natural resources. Some cities developed right on top of those resources, whereas others emerged close enough to serve as supply hubs. Others formed in strategic locations where their residents could gather or process resources from vast regions. Montreal and Saint Louis started as fur-trading posts; Denver served as a transit point and supply depot for mining in the nearby Rockies; Chicago became America’s greatest nineteenth-century boomtown by raking in the West’s bounty of timber, beef, and grain.6

Many large American cities developed on sites with access to water for transportation. Harvesting natural resources doesn’t do you much good if you don’t have a means to bring them to market. Most of this country’s oldest and biggest metropolises sprouted up by the seashore, and more than half of all Americans still live within fifty miles of an ocean coastline. Protected estuaries with high ground for building and deep water for shipping have worked well as city sites. Cities not located on coastlines are often connected to them by navigable inland waterways—Pittsburgh and Minneapolis are obvious examples.7

Coastlines and rivers corridors are not only favored spots for cities; they also tend to attract a lot of wildlife. This is especially true for river mouths and deltas, which pack diverse habitats into small areas, are highly productive, and provide crucial pathways for migrating fish, marine mammals, and birds. Cities like Sacramento and New Orleans now occupy many of these soggy landscapes.

A reliable source of potable water was often a crucial factor in determining the location of a settlement. Consider the example of Phoenix, America’s fifth-largest and second-driest major city. Some two thousand years ago, the Hohokam built canal systems, farms, and thriving villages along the Salt River. Later native peoples repurposed much of this infrastructure, creating vibrant societies of their own. An 1867 account of the valley described “a sparkling stream the year round, its banks fringed with cottonwood and willow; the land level and susceptible of irrigation. The evidences of a prehistoric race were everywhere in evidence.” A carpet of annual grasses, providing “a most excellent fodder for stock,” covered the higher ground. This water and forage attracted diverse wildlife, including hundreds of migratory bird species, aquatic animals such as beavers, and grazers like elk and antelope, not to mention the wolves, pumas, and jaguars that hunted them. The desert city of Phoenix now sprawls over this once lush and well-watered landscape.8

Other cities developed on sites that are often inconveniently wet. Miami is blessed with access to vast wetlands, forests, and the only coral reefs in the contiguous United States. But it is cursed with water lapping at its borders on four sides: to its east is the Atlantic Ocean, to its west is the Everglades, from the sky above comes the wet subtropical weather that makes it America’s second-rainiest big city, and below is porous limestone that is filling up with salt water as the sea level rises. Houston grew into a major metropolis after the Great Galveston storm of 1900 drove Gulf Coast development inland. Decades of reckless construction then left what is now the country’s fourth-biggest city vulnerable to a series of floods, culminating in 2017 with Hurricane Harvey. Wetlands that had been converted into reservoirs and later into subdivisions filled with water, pushing thousands of snakes, alligators, raccoons, and other creatures into suburban neighborhoods and reminding Houstonians, at least for a few days, that they still lived in the bayou.9

Even many cities that appear to have no good ecological reason to be where they are still often seem to be located in oddly biodiverse areas. Las Vegas’s very existence depends on vast quantities of water and power from the Colorado ...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Where the Wild Things Are, Now

- 1: Hot Spots

- 2: The Urban Barnyard

- 3: Nurturing Nature

- 4: Bambi Boom

- 5: Room to Roam

- 6: Out of the Shadows

- 7: Close Encounters

- 8: Home to Roost

- 9: Hide and Seek

- 10: Creature Discomforts

- 11: Catch and Release

- 12: Damage Control

- 13: Fast-Forward

- 14: Embracing the Urban Wild

- Coda: Lost and Found

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index