![]()

CHAPTER 1

Situating Information Literacy Research

Introduction

In 1974 Paul Zurkowski (1974), reflecting on the capabilities of people to cope with the emerging complexity of the information age, coined the term information literacy. The practice of information literacy was connected to the achievement of economic and organisational goals and to people’s ability to solve problems and workplace tasks (Lloyd, 2010a). Zurkowski’s observation about the role of information and people’s capacity to deal with information in complex situations acted as the catalyst for information literacy research within the library and information science field. The concept of information literacy has been adopted by public, school and academic librarians and is now established in the profession as a core aspect of professional practice.

Research into and about information literacy has also become a significant field for library and information science academics, who investigate the phenomenon from many different perspectives. While some researchers are interested in information literacy as a skill or an inquiry strategy which supports learning, other researchers attempt to understand the complex dimensions of the practice, i.e. what conditions enable and/or constrain it, and how the practice contributes to formal and informal learning leading to the development of information landscapes and to building information resilience.

It is central to our professional information literacy practice (as researchers or practitioners) that we develop a critical understanding of how information literacy is shaped and that we understand how research is operationalised and executed, either to undertake our own research or to evaluate the corpus of research about information literacy that we use to support our own work. The aim of this book is therefore to provide a primer or guide to the range of qualitative research, theories, methods and techniques being employed to investigate and describe the complexity of the practice.

A theory of information literacy landscapes

This book is framed and positioned by the theory of information literacy landscapes described by Lloyd in 2010a; 2010b; 2017a. Information literacy is view by her as:

A practice that is enacted in a social setting. It is composed of a suite of activities and skills that reference structured and embodied knowledge and ways of knowing relevant to the context. Information literacy is a way of knowing.

(Lloyd, 2010a, extended in Lloyd, 2017a)

The theory presents information literacy in the broader sense, as a situated practice that is shaped by the conditions, arrangements and discourses of a social site, rather than restricted to skill-based enactments related solely to text-based mediums (print or digital). According to this theory, the practice of information literacy is also present in a corporeal and social sense. As a way of knowing, the practice connects us to epistemic/instrumental ways of knowing, and to local, nuanced, contingent and embodied forms of knowledge that reference the context/s in which we operate (Lloyd, 2005; 2006a).

Key concepts

Information literacy is a complex practice, and in the information-rich environment of a post-truth world, is becoming an increasingly important form of literacy practice. When executed, this practice enables a person to understand the sources and sites of knowledge and ways of knowing that contribute to becoming situated and emplaced. This knowledge, in turn, affords a person the opportunity and capacity to think critically about the way information is operationalised on a sociocultural level (what is valued), and how it is operationalised materially, i.e. through tools, mechanisms and source-related practices through which information is produced, reproduced, circulated, disseminated and archived. This idea extends from print through to digital landscapes. The practice has, therefore, relational, situational, recursive, material and embodied dimensions that are drawn upon to make it meaningful.

While the language may change to accommodate the perspective of a researcher or practitioner, in reality the core structure and trajectory of the practice does not. Foundationally, information literacy is a practice, that like all practices, is enacted in ways that:

• draw from modalities of information that reference the knowledge base of the specific setting and broader context by members of the setting

• engage in activities that form part of the individual and collective performances

• use the material objects and artefacts that are sanctioned as part of the performance.

Becoming information literate requires the development of a meaningful landscape and the range of activities that enable information to be drawn from that knowledge base. This requires competence (knowledge of context and relevant skills) and an ability to relate to social and material practices (Shove, Pantzar and Watson, 2012).

Unpacking information literacy theory

The theory of information literacy that frames the development of a book on research methods draws from several concepts. One that threads throughout the text is the representation of information as ‘any difference which makes a difference in some later event’ (Bateson, 1972, 315). Bateson argued for information as a ‘bit’ or an idea which, when accessed, made a difference, and this implies a qualitative change to knowledge, including ways of knowing. This change may produce positive or negative effects (Lloyd, 2017a).

To construct a way of being in the world, people draw from information environments, which are described here as larger stable sites of knowledge (e.g. health, education, politics, religion) to create information landscapes that reference the sites of knowledge and ways of knowing central to the construction of their intersubjectivity (shared sense of meaning). These enable their individual subject agency (to act). Intersubjectivity represents the common reference points and knowledge shared by people who are collectively engaged in shared endeavours or practice. For example, the larger project of being a librarian draws from previous experiences, histories, social and material practices of librarianship and ways of working as a librarian that are shared among those who engage with this endeavour. Subjectivity refers to an individual’s belief drawn from the intersubjective project. The theory of information literacy presented here views intersubjectivity as the dominant aspect driving thought and action and contributing to personal or subjective views and action (Lloyd, 2017a).

Information literacy landscapes

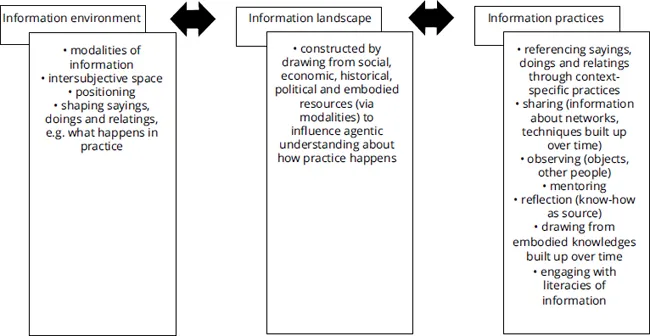

The practice of information literacy is conceptualised as creating an information landscape (Lloyd, 2006b). Information landscapes are shaped by modalities of information representing the ways of knowing about the collective forms of knowledge, i.e. they are drawn from the information environments that people interact with – health, workplace, educational, sporting or leisure (Lloyd, 2006b). These modalities may be social (and accessed by our interaction with each other), epistemic (the expressed rules and regulations and discourses that legitimise practice) or corporeal (that are referenced through our embodied actions – as practice). Drawing from these modalities allows people to shape their information landscapes and to enact literacies of information which, in turn, act to reference the social site (Lloyd, 2005). These dimensions are entwined, and the enactment of information literacy is predicated on the agreed-upon shared meanings about a project or collective endeavour, and on the activity and action involved, thus supporting the reason why information literacy is enacted in a way that is meaningful for the setting (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Information environment and landscape (Lloyd and Olsson, 2019)

Enacting information literacy: literacies of information

The practising of information literacy references the values, knowledges and ways of knowing that are inherently valued within a social setting. For example, practising information literacy in a scientific setting will reference the types of knowledge and ways of knowing that are legitimised and valued by the discipline. The scientific way of practising information literacy may differ in other settings such as playing soccer, where the practice of information literacy may emerge corporeally and favour knowledges which are developed through physical experiences of playing soccer and therefore embodied.

Enacting the practice scaffolds a person’s being in the world, through the development of ways of knowing, and affords opportunities for alignment with, and membership of, a community. This allows the practice to develop in ways that are valued by the social site and promotes information resilience (Lloyd, 2015b). Information literacy does this by enabling access to knowledge about the way an information landscape is shaped, enabled and constrained and to knowledge of the information activities, competencies and skills required to enact and execute the practice in context. Information literacy connects people to the social, epistemic/instrumental and corporeal dimensions that reference being in the world.

We practise information literacy and in that moment of practice, information becomes a practice. Enactment has been conceptualised through Weick’s studies of organisations. In that context, Weick (1995) suggests that enactment entails a process (something being played out – an activity) and a product (the environment). Weick describes enactment as a two-step process: the first step being the bracketing of the field of experience as the basis for preconceptions (the ways things should be done/understood) and the second the guiding of people’s activities or actions by preconceptions (the ways things are done/understood). In relating this process to the practice of information literacy, it can be argued that enactment occurs in a specific context and is recognised because it reflects the way people work with information in that specific context and the knowledge they agree upon. According to Weick, the outcome, or product, of enactment is social construction and is always subject to interpretations. In a similar vein and also within the context of organisational studies, Orlikowski’s (2002) idea of knowing in practice draws from Weick’s position that enactment is action-based and evidenced by ‘acting, doing and practicing’ (Niemelä, Huotari and Kortelainen , 2012, 214). Weick’s concept of enactment is relevant to a theory of information literacy because it highlights the emergence of social (overt and nuanced) and material activities that enable and support access to information modalities (Lloyd, 2006b) within a social site. Information literacy is often viewed as something that is attained, and this attainment is often reduced to the targeted development of information skills.

When viewed as an enactment that references ways of knowing and manifests through literacies of information the focus is directed towards understanding social and material activities that help to build a social practice. This allows us to delve deeper into the complex interactions that are foundational to questions about how and why information literacy, as an information practice, emerges or is viewed in relation to context. The concept of enactment has been employed by Lloyd (2012) to highlight for researchers the ontological and epistemological conditions that shape the practice and should feature in research into information literacy practice. This suggests that, ontologically, enactment is expressed as an understanding of what constitutes information and knowledge, and it emerges epistemologically as ways of knowing and practising.

Enactment emerges in practice as an expression of and with reference to ‘the social’ (Schatzki, 2002). When a practice is enacted, it is brought into being. When we enact information literacy, we are referencing the realities of a social site, such as the knowledges and ways of knowing (activities and skills) that are valued and legitimised. Consequently, the discourse that often surrounds what constitutes information literacy practice may seem to be different when the practice is described by academic researchers and by practitioners, teachers or librarians, even though the foundational elements are actually the same. The enactment of information literacy practice occurs socially, corporeally and materially, with all three entwined modalities patterned and shaped ontologically and enacted through the epistemological lens of context. Social and corporeal modalities reference vernacular or local literacies, that constitute important and often invisible forms of information work, connecting with and creating tacit, contingent or embodied forms of knowledge. Material practices and their enactment through technologies or documents (for example, digital literacy, media, and visual literacy) are often the most visible to researchers and educators and the most often discussed in the library and information science literature. To represent social, corporeal and material enactments more accurately, the concept of literacies of information is adopted here in preference to the term ‘information literacies’ (Limberg, Sundin and Talja, 2011). Information literacies is used by these authors to highlight the variation in emphasis that can occur when researching information literacy according to different theoretical traditions. The juxtaposition to literacies of information is not merely a semantic exercise but is intended to emphasise the inherently central role of information enacting in contemporary literacy practices such as digital, visual and media literacy and thus foreground how the elements of information literacy emerge as the core focus for researchers and for practitioners in the library and information science field (Lloyd, 2017a).

Advocating the use of the phrase ‘literacies of information’ highlights that the practice of information literacy is enacted and shaped or reshaped according to the doings or sayings of a site (Lloyd, 2010a; Schatzki, 2002). This allows us, in the first instance, to be open to acknowledging the different views that participants hold about what constitutes information, knowledge and ways of knowing. Consequently, emergence and enactment become anchored ontologically within the domain of the knowledge claims about truth (such as what knowledge is valid and what counts and contributes to reason), and epistemologically in language games (such as how/what knowledge and ways of knowing are sanctioned) (Wittgenstein, 1958/2009). By this account, information literacy is positioned as being primary and foundational, along with reading and writing practices, rather than being adjunct to them.

Becoming information literate is realised through its enactment and references the cultural-discursive and social-political arrangements of the site (Kemmis and Grootenboer, 2008). The material-economic arrangements (Kemmis and Grootenboer, 2008)...