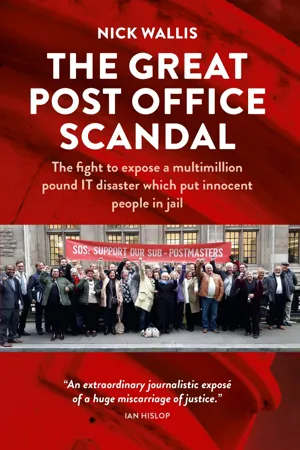

The Great Post Office Scandal

The Fight to Expose A Multimillion Pound Scandal Which Put Innocent People in Jail

Nick Wallis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Great Post Office Scandal

The Fight to Expose A Multimillion Pound Scandal Which Put Innocent People in Jail

Nick Wallis

About This Book

The Great Post Office Scandal is the extraordinary story behind the recent ITV drama series Mr Bates vs The Post Office.

This gripping page-turner recounts how thousands of subpostmasters were accused of theft and false accounting on the back of evidence from Horizon, the flawed computer system designed by Fujitsu, and how a group of them, led by Alan Bates, took their fight to the High Court. Their eventual victory in court vindicated their claims about the defects of the software and exposed the heavy handed attempts by the Post Office to suppress them.

The book also chronicles how successive senior managers, business leaders, lawyers, civil servants and Government ministers, at best failed to expose the injustice or, even worse, sought to cover it up, resulting in one of the largest miscarriages of justice in UK history.

The author, Nick Wallis, is a journalist and broadcaster who has been reporting on the scandal for over ten years and who acted as script consultant on Mr Bates vs The Post Office, the ITV drama that brought the affair into the national consciousness.

As the public inquiry reaches its climax, and senior figures such as Paula Vennells come to be questioned, The Great Post Office Scandal reveals the full scale of what happened and will leave you enraged at how so many of our trusted institutions allowed the saga to go on for nearly a quarter of a century, shattering the lives of thousands of innocent people.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Horizon Scandal Fund

- About The Author

- Reader Note

- Foreword By Seema Misra

- Introduction

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Who’s Who

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index