- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

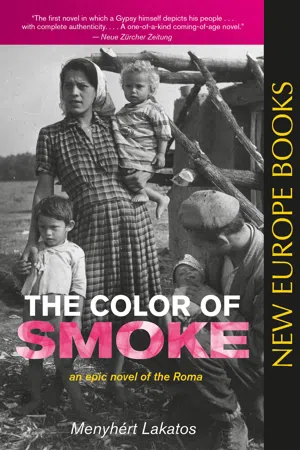

The first major novel about Eastern Europe's Roma, or Travelers (Gypsies), by a Romani author, The Color of Smoke is both a work of passion chronicling one young man's rise to manhood and an epic work that conjures up a dark era of world history. It is an undiscovered classic that has been published in several languages since its 1975 appearance in Hungary--but never before in English.

Inspired by the author's own boyhood in World War II-era Hungary, it is a beautifully written coming-of-age story of a Romani boy torn between the community of his birth and the mainstream society that both entices him and rejects him.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Color of Smoke by Menyhert Lakatos, Ann Major in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Literature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

ONE MORE BARELY NOTICEABLE SIGH, then his eyes became fixed into an eternal gaze. Time froze on his stone-brown face, and Tsino Petro1 became but a memory—a lasting memory of which Tsino Petro’s daughter, Old Liza, or Grandma, to me, told stories during seemingly endless nights. Her stories conjured up old memories when time was measured not in months and days, but in the flowers that blossomed and the leaves that fell a hundred and one times under and over her father, as she used to say.

We were the people in whose blood life had lit a fire; neither the winds nor the winters—be they ever so fierce—could extinguish its flame. I knew Grandma as a small, wizened old woman, who sat only on the floor. When talking, she rested her chin on her knees, her stemless pipe clasped between her palms. She was a perfect custodian of bygone centuries. The world we lived in was alien to her; being confined to one place was, to her, servitude. Grandma was just too old to change her ways; the twelve years she had spent among us could not dislodge those earlier times. She felt cold even on the hottest of days. With her long outer skirt thrown upward over her shoulders, and squatting with her feet tucked under her, she smoked relentlessly. In the winter she often slept on the porch, since she couldn’t bear the hut’s stifling air. This embarrassed Papa, her son, but if he complained about it, she just waved her hand dismissively.

“Don’t take any notice son, let those Romungros2 talk all they like, they’ve gotten used to this robiya3 but I get coughing fits indoors, and the children can’t sleep properly on account of me.”

We never once heard Grandma coughing outside.

Sometimes she would crouch in front of the wood-fired cob oven, which, in the kitchen adjoining the main room, was topped off by an old tin can that served as the chimney. There she would feed green acacia twigs through the large opening and stare as they frothed and whistled and curled up amid the flames. The wind often blew its thick, acrid smoke right at us, stinging our eyes.

Grandma could hardly wait for spring. She swept our tiny yard each evening, picking up anything that would burn, like rags and dried horse dung. For a while we thought she did so to keep it clean.

When Papa settled down by the oven and stared into the flames, especially when the air was thick with wood smoke, his face became transfigured as if in prayer.

This feeling wasn’t the same for me; all the smoke did was to make my tears mingle with my dripping nose, which Grandma kept wiping with the hem of her skirt.

Later I got used to it and, after cavorting all day, I would rest in front of the oven. Grumpy-looking old folks also gathered round, their skin shiny and dark, like May beetles, and they chased away children who disturbed their thoughts or conversations. They were always telling stories, it seemed. They conjured up their memories from such a distant past that only they could make sense of them. Their deep roots were nourished from a world that to others was by now only history.

Like yellowed sheets of parchment, they bore witness to the history of centuries past. Time did not rush past them; the youthful stories of their fathers and grandfathers lived on in them, faithfully preserving the traditions of ages long gone.

Their mute, wrinkled mouths spoke of the past as their eyes stared at the small leaping flames, flames that perhaps reminded them of the stomping of their long-gone wild horses. Their eyes, akin to the moonlight, at times became swathed in a cloud or else lit up with happy, wonderful purity when they reached a cherished memory along the muddy, dusty highways of time. Scents of forests and mountains emanated from their thoughts, blood bubbled up in their veins, and they could hear the sound of the brisk rivulets on whose banks they had rested long ago.

We went from big water to big water. Grandma didn’t use the word “sea,” perhaps because she didn’t even know it; all she said was bari pani.4 I never did find out whether that passage she spoke of was from the Black Sea to the Adriatic or from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

Grandma burnished even the foggiest youthful memory to a luster. She reminisced about her ancestors as if they had been the personification of courage and brains. Chache Roma,5 she used to say about them. To her the later generations of Gypsies were too yellow-bellied, too soft, to endure danger and hardship.

“The road was hazardous in winter but our carts never broke down; the horses we used were of the best. Sure, anyone lagging behind perished. Life in Ungriko Them6 was like being in robiya, but that’s where we found the best horses and light carts with iron axles.

“Had a hundred dragons guarded them,” Grandma continued, “we still would have taken them. Tsino Petro was molded where fear was unknown. He didn’t let anyone into his space, and any person doing so had to pay with his life. All could do as they pleased, but anyone trespassing on another was put on kris.7 Tsino Petro got his nickname, Little Peter, for his build, but he certainly wasn’t a scaredy-cat, why, he’d spit right into a snake’s mouth.

“Once, long ago,” she said as she always did when starting one of her stories, “in late fall, we were in Serbia when a group of red-capped Gypsies showed up at our camp. Real steeds were prancing about in front of their rickety carts, but there was no sign of women and children. They helped a gray-bearded old man off one of the carts. He looked awfully sick. They asked us politely to let him sit next to our fire. ‘Sit down, old man,’ our people said. ‘Tell us, what brought you here?’ These strangers all wore dappled kerchiefs under their caps. We wondered who they were, these people who spoke our language so well.

“Well, the old man then took off his cap and his kerchief, ever so slowly. First he bent one side of his face toward the fire, and then the other. In place of both his ears were gaping wounds, and his eyes were watery, like black grapes. The others then also removed their kerchiefs; not a single one of them had ears. They couldn’t get a word out for all their sobbing. Our women burned mushroom veils and spread the ashes on their wounds. It took the newcomers quite a while to tell their story.

“ ‘A bunch of soldiers surrounded us,’ the old man began. ‘What could we do? We couldn’t try to run off, not with the women and kids still there. The soldiers then beat the men into a group and drove them into the woods. Their commander spoke, but we didn’t understand. What he was saying was that they would cut off our ears, kill the women and children, and let us go.

“ ‘That was when God took our good sense away.’ The old man tried to swallow his tears, but his lips trembled with silent sobs nonetheless. ‘We thought he was saying that if we let them cut our ears off, we could leave. That if we didn’t, they’d kill the children and women. What else could we do? We endured it without letting out a peep. Bloodied and ashamed we headed back toward camp. The soldiers were still there, but we found ourselves wading knee-deep in the blood of our women, children, and horses.

“ ‘They hadn’t left a single creature alive, only us without ears for everyone to see what befalls those who dare trespass on their territory. When we saw the bodies, we attacked the soldiers with our bare hands, our bare teeth—they killed many of us, but in the end it was them who had to flee. These here are army horses, but what good are they to us? We’d rather be dead ourselves. They destroyed our dulmuta,8 leaving us doomed to be the Gypsies’ outcasts. No one will believe that it wasn’t our own people who did this to us for some treachery.’

“Tsino Petro now spoke,” Grandma said. “ ‘Unhitch your horses,’ he said, ‘and sit closer to the fire. Tomorrow is another day.’ By next morning the old man was dead from grief. They didn’t give him a big funeral. They just broke his cart shaft in two, then peacefully smoothed down his grave. The rest of them stayed behind, orphaned, waiting for our father to invite them into his dulmuta.

“That same afternoon,” she recounted, “he gave them the widows and marriageable girls and sent them on their way.”

Tsino Petro’s dulmuta changed its direction, gradually moving across Hungary and Romania up toward Russia, but the harsh weather, shaggy little horses, and wretched villages they found in Russia held out little hope. It was there that Grandma first got married, and as a souvenir, she brought back-for back they came—a little boy named Ivan. He was her first child.

Only around 1870, in southern Hungary, did they again cross paths with the earless folk, who having gone on to multiply greatly, now called themselves “Petro’s People” after Tsino Petro, from whose dulmuta they had been reborn.

The old folks in our settlement would sometimes refer to the phiripe9 in telling their tales, and for a long time I wasn’t sure just what they were talking about. What I did know was that most Gypsies in Europe had migrated north, from the Balkans; of those that had split into two branches in Bulgaria—one moving north along eastern Romania, the other across Serbia-both passed through Hungary.

The tribes had then split into smaller units, each of which called itself a dulmuta. Not that they had broken up, exactly; no, it was like in the army, where a company is made up of platoons and the platoons of squadrons. True, the term dulmuta had previously signified a tribe, whereas each of these small groups was but a fragment of the whole that once existed.

You might think all these small groups would nonetheless have still belonged to something larger, something that bound them, kept order, and provided guidance. Each dulmuta was, after all, bound by a set of tribal values. But did these values end where the dulmuta did? Was an overarching “tribal law”—whose details were indeed lost on so many people, if they recognized them at all—no longer binding on each separate group? In fact it was! Everyone was obliged to uphold every unwritten law that regulated their lives regardless of which dulmuta they happened to belong to. This is shown, among other things, by the fact that no dulmuta could use the place another dulmuta traveled in—namely, its phiripe.

On several occasions I quizzed Papa about matters concerning the phiripe even though he was reluctant to let me in on Gypsy secrets I couldn’t figure out on my own. All too often his only answer was that I’d find out once I got older. His silence only made me more curious.

As for Grandma, she pretended not to understand me to begin with, and it was obvious that not even she wanted to talk about the phiripe. It seemed that this word, too, was secret. And so I kept pestering Papa about it, and he bawled me out more than once for being nosy. But, in the end, he tired of resisting sooner than I did of persisting.

The dulmutas, he at last explained, had divvied up among themselves the phiripes in the countries they passed through. But just how they went about it, no one could say exactly. Not by conquering those lands, that much was certain. No, insisted Papa, they never had territorial disputes. No matter how tiny a dulmuta was—even if nothing more than a family on a single horse-drawn cart-not even the oldest folks among us could recall a case in which a bigger, mightier dulmuta had stolen the territory of a smaller, weaker one. But as the generations came and went, and as the past gave way to the present day, the desire for material wealth—and for the possession of territory that held its promise-stirred ever more in Gypsies, too.

“The phiripe had to be respected by all,” Papa said, meaning that if some Gypsies violated it, other dulmutas came swiftly together to take collective action against them. The phiripes were, in short, “hunting grounds” in both the good and bad sense of the term—ensuring that the Gypsies who passed through them could continue their nomadic ways.

All this was a bit beyond me. Wandering like nomads still required something to get by on, did it not? As for tools and other possessions, well, once they wore out, they had to be replaced. If wandering was the main aim in life, then the phiripes must indeed simply have been hunting grounds. But if wandering wasn’t so much a matter of instinct, but more a means of acquiring goods illicitly, then why hadn’t the dulmutas sought to take away one anothers’ territories?

Papa only cast me an impatient stare when I pressed him with such questions, and he didn’t say another word. At times like that, I got back at him by not taking his horses to pasture for days.

“Why don’t you ask Grandma instead?” he ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- A Note to the Reader

- Other Books by This Author

- About the Author

- About the Translator