![]()

1

Finding the language

Legal language is sometimes very obvious and easy to find. When being arrested by the police or signing a contract, the language is clearly related to the law. But legal language may also be entirely invisible. Boarding a bus, for example, may not involve any language at all. However, once a person is allowed to get on the bus, a contract has been formed. These contracts contain a number of terms and conditions, setting out the rights and responsibilities of both the passenger and the bus company. Unless something goes wrong, this legal language remains hidden. Nevertheless, if one starts looking it is possible to find it. Once one is aware that rules exist it is possible to investigate them in more detail.

A travel pass commonly used in London is the Oyster card. On the front it states: ‘Issued subject to conditions – see over’. Turning the card over, one finds:

Example 1.1

The issue and use of this Oyster card [the name of the travel pass] is subject to TfL’s [Transport for London’s] Conditions of Carriage, copies of which are available at any of our ticket outlets, or on our Customer Services web site at www.oystercard.com or the Oyster card helpline [telephone number]. Where this Oyster card is also valid for use on another operator’s services, the Conditions of Carriage of that operator will apply in relation to travel on its service. Copies may be obtained from those operators (Transport for London).

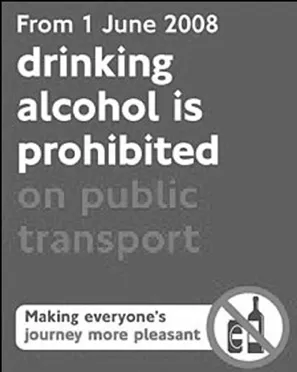

If a passenger reads the card, and finds out that terms and conditions exist, some effort will still be required to ascertain exactly what these terms and conditions are and how and where they apply. Fortunately, in commonly used services like public transport, important rules – and especially changes to rules – are usually communicated in some other way. Image 1.1 shows a poster that was displayed in London train stations in 2008.

This looks very straightforward. Passengers are no longer allowed to drink alcohol on public transport. But this is not the full story. In the case of the alcohol ban, finding out what it means involves looking at the terms and conditions mentioned on the back of the Oyster card, as Transport for London’s ‘Terms and Conditions of Carriage’ set out the details of the alcohol ban.

Example 1.2

4.5.2 Alcohol ban – on our buses and Underground trains and in our bus and Underground stations, you must not:

• consume alcohol

• be in possession of an open container of alcohol

You may be prosecuted if you disobey these requirements on our Underground trains and in our bus and Underground stations.

(Transport for London, 2012, p. 10)

Activity 1.1

Look at these lines closely. Do they include the same information as Image 1.1?

There are a number of things to consider here, not all of which are clear from the cited section. First, these conditions of carriage run to over 50 pages. Passengers are not handed a book to read before boarding public transport or when buying a ticket. As noted, however, boarding a bus and paying the fare means a traveller is nevertheless bound by these conditions. Second, the terms and conditions are not the same as the poster. While the poster makes clear that alcohol may not be consumed on public transport, the terms and conditions state that one may not be in possession of an ‘open container of alcohol’. Thus, third, it is important to know what ‘open container of alcohol’ means; would this include a bottle of gin that had been opened but was now sealed? Fourth, finding out what ‘alcohol’ includes requires consulting another text, the bye-laws that regulate London transport. This is important, as lots of liquids (like perfume and mouthwash) include alcohol. Are they included in the ban? But the bye-laws do not contain this definition. Instead, they direct the reader to another text, the Licensing Act 2003, for the definition of ‘alcohol’. In this case, the legal meaning and the ‘common sense’ meaning of ‘alcohol’ are the same, that is, perfume and mouthwash are not ‘alcohol’ for the purposes of the ban. But it is not always the case that common sense and the law coincide in this way (Slocum, 2012).

The rest of this chapter provides examples of legal language and language used in legal contexts. These examples make three things clear. First, law uses language in surprising ways; second, the way people use language can have legal consequences; and finally, looking at the language of law can help to understand language more generally.

• Legal language is not always obviously present.

Twittering away

In January 2010, much of the United Kingdom was affected by heavy snowfalls. Robin Hood Airport, near Doncaster and Sheffield, was closed, frustrating the plans of many travellers. One such person, Paul Chambers, vented his impatience on Twitter. The message that he sent to his 600 or so followers, with expletives removed, reads as follows:

Example 1.3

Crap! Robin Hood Airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit [to sort it out] otherwise I am blowing the airport sky high!

(Chambers v DPP [2012] EWHC 2157 (Admin) pgh. 12)

Activity 1.2

Consider this tweet. What is the author expressing? Is it a real threat to blow up the airport? Would a jury conclude that this is ‘menacing electronic communication’ and so illegal? If there had been a recent series of bombings of airports, would the tweet be read in the same way?

The author of this tweet was charged, tried and found guilty of sending a ‘menacing electronic communication’ (BBC News, 2012a). Under the circumstances, it would be reasonable to argue that the tweet was not a serious threat. The public reaction to Mr Chambers’ conviction demonstrated that a great number of people understood that the ‘threat’ to blow up the airport was not a serious one, but was instead the expression of a traveller’s frustration. Nevertheless, this tweet was read very literally by airport personnel, police and – at least to start with – the courts. Eventually, two years after his conviction, the High Court quashed it (BBC News, 2012b). The case is rightly seen as one relating to freedom of speech (see Green 2012), but it is also about the interpretation of language.

Whether or not something is menacing may be a question of interpretation and context. While the tweet clearly has the form associated with a threat, ‘Do x or I’ll do y’, whether it is understood as a threat depends on how one orients to the utterance; that is, it depends on the context in which the message is placed. In relation to language, ‘context’ can mean any number of things, including the identity of the speaker and audience, the other language in the text, and the forum in which the text is produced. Threats are considered in detail in Chapter 3. For the moment, it is enough to notice that communication is not always straightforward. Even ‘literal’ language has a context that needs to be taken into account.

Activity 1.3

Look again at the tweet about Robin Hood Airport above. While some people understood it as a real threat, others understood it as a joke. Why is this? Think about all the factors that led to these different interpretations.

The six functions of language

Even if a conversation only involves two people, there are a number of other factors that need to be considered in order to understand what’s going on. Indeed, the identity of the people involved in a communication can make a significant difference to the meaning of an utterance. If a known member of a ‘terrorist’ group made the twitter ‘threat’ above, it would be reasonable to construe it as a threat. Further, if the addressee of a threat is a public figure (Fraser, 1998) it is more likely to be treated seriously. How the message is communicated may also make a difference. If the message itself contains detailed demands, it is also likely to be treated as a serious threat. Thus, there are a number of factors involved in all communicative events; each factor has a function. The model introduced here comes from the work of Roman Jakobson. He argues that ‘Language must be investigated in all the variety of its functions’ (1960, p. 353). His model has two aspects: the first sets out the factors involved in any communicative situation; the second enumerates the functions that are attached to these factors (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

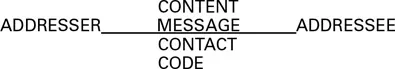

Figure 1.1 Factors involved in verbal communication (Jakobson, 1960, p. 353).

A brief explanation of these six factors is required before their functions can be discussed. The ‘addresser’ and ‘addressee’ are straightforward; these are the speaker (or writer) and the hearer (or reader) respectively. Of course, not all communication situations involve only two people. There may be multiple addressees, for example. The ‘message’ between them is what is communicated. While this looks straightforward, the message can only be understood in relation to the other factors. I will return to the message presently. The ‘code’ is perhaps best thought of as the language variety. Thus, the code may be English or French, ‘ordinary’ language or legal language. For communication to be successful, this code has to be shared. If the addresser is speaking French and the addressee is an English monolingual speaker, it makes no sense to talk about ‘message’. Indeed, the lack of a common code is a recurring issue in the area of language and the law (see Chapters 4 and 6).

While Jakobson sets out his six factors in relation to verbal communication, communication may take place verbally or through a written text (or indeed using other kinds of signs; see Chapter 10). This variation can be accounted for in terms of ‘contact’, that is, the ‘physical channel and psychological connection’ (1960, p. 353) between the addresser and addressee. Finally, the ‘context’ is the common ground needed for communication over and above the code. For example, if a speaker starts to discuss ‘that chair’ while pointing to a space, it would be reasonable to expect to find the chair in the space she indicates. Co-present communication brings its own context, that is, the surrounding space. The context also refers to the immediate verbal context, the other words and phrases that occur in the utterance. In written communication, the author would have to refer to ‘a chair’ before ‘that chair’ could be invoked in any sensible way; the chair needs to be introduced as ‘co-text’ before it can form part of the context.

Figure 1.1 shows that while there is always an addresser and an addressee, there is a great deal which sits between them. The most obvious link between the add...