![]()

Part One

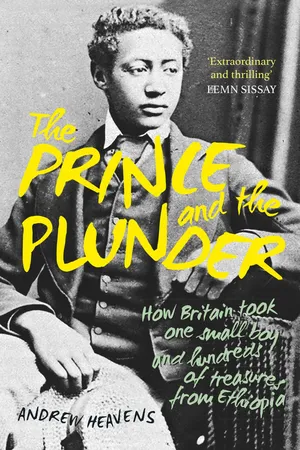

The Prince

![]()

Chapter One

Home

‘Here [in the happy valley] the sons and daughters of Abissinia lived only to know the soft vicissitudes of pleasure and repose, attended by all that were skilful to delight, and gratified with whatever the senses can enjoy … The sages who instructed them, told them of nothing but the miseries of publick life, and described all beyond the mountains as regions of calamity, where discord was always raging, and where man preyed upon man.’

The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia

On the first day of March 1841, John Bell set off from Gondar on the lookout for adventure. Leaving the old city’s castles and incense-filled churches behind him, he rode south, down past villages and hills and woodlands, following the winding course of the Angereb River.

Turning a bend in the track, he got a good view of vast expanse of Ethiopia’s Lake Tana spread out in front of him, dotted with island churches and monasteries. The fresh, clear highland air brought everything closer. Out in the glinting water he could make out the grey mass of his first hippopotamus basking on a shoal.

The towering son of a family of roaming British seafarers had already seen more than his fair share of wonders and new horizons. He had been born on Malta, learned French, Maltese and Arabic at the missionary school in Sliema and earned his first living travelling with merchants and explorers, acting as their universal factotum and translator. While still in his twenties, he had decided it was time for some exploits of his own, so he had sailed down the Red Sea, stopped off on the coast of East Africa and climbed up into the near-mythical mountain empire of what was then called Abyssinia. His plan: to find the source of the Nile, to fill in some of those great blank spaces on his maps of the interior, to win a little recognition back home and, above all, to forge his own future.

So that was what he was doing as he wandered south down the edge of Lake Tana. Adventuring had never been easier. Day after day he rode over gently sloping hills in the shade of acacia trees, crossing streams, shooting guinea fowl for dinner and sipping the coffee brewed by his retinue of servants. Barely a week into their journey, the small party wound its way through a hilly, heavily wooded territory, over a stream, past a church and up along a lonely, woody path, bounded on both sides by high bushes. Which is where the bandits struck.

Eight men armed with shields and lances jumped out of the bushes and knocked Bell to the ground. They slashed at his arm as he tried to protect his head. One servant, Gabriote, ran to his side with a sword. Bell got up, pulled out two pistols and held the attackers at bay for a second. Another rush. Bell took aim, but his first pistol misfired. So did his second. He had loaded them two months earlier and they had hung unused by his side during his wandering idyll. He took one of the pistols by the muzzle and used it as a club, lashing out. The men closed in and surrounded them, jabbing with their spears. One raised a lance and stabbed Bell in the face, sinking the point between his eyes. Blood gushed out, nearly blinding him as he floundered on, weaker and fainter. Gabriote, still at his side with five gaping wounds, still trying to keep the men away, began to totter and slumped down. One of the bandits grabbed his sword as he fell. The gang scooped up a few other bits of baggage scattered around and ran off, leaving Bell and Gabriote lying on the blood-soaked ground.

A pause, then the other servants emerged from their hiding places. The two wounded men managed to get to their feet, gather some belongings and slowly, slowly head back to the track, staggering along, falling three or four times along the way. After about half an hour of agonising stumbling they reached the town of Qorata and collapsed at the door of a church.

By sheer luck, a merchant that Bell had met on his way into the country had a house nearby and took them in. One of the attendants gave Bell a cup of the local beer, but when he drank it some of the liquid came seeping out of his eyes. On closer inspection, he later wrote in his journal, the spear thrust into his face ‘was found to have entered the superior part of the nasal bones, to have pierced the superior palate bones and to have run along the superior maxillary bone finally making its exit just below the right ear, most wonderfully avoiding the large vessels placed in that neighbourhood’. Gabriote was in no better state.

After a few days, wounds still healing, Bell had recovered just enough to start making inquiries. It turned out that the eight shifta – a loose term covering a wide range of armed men from bandits to rebels to militia fighters – were under the command of a senior officer serving Ras Ali, that region’s ruler. From his sickbed, Bell demanded investigations, compensation, punishment for the men who had dared to attack the British explorer and his party. What he got in return was a measure of sympathy from his immediate hosts but, beyond that, bemusement. The wheels of Ethiopian politics, it turned out, were not prepared to stop in their tracks to investigate and prosecute a bandit attack on a notoriously bandit-infested road. No one had died. Shifta happens. That was that.

Bell’s merchant friend sent men to the scene of the attack and retrieved one of the pistols dropped in the melee. ‘When I recovered a little I went to see the Ras, and asked him to punish the robbers,’ Bell wrote. ‘He refused, saying they were badly wounded as well as myself. He then dropped the subject declaring he would not hear more about it; consequently I got up and walked out of the place.’

What to do when the rest of the world refuses to play along with the grand narrative running in your head? You can pack up and go home. Or you can keep on keeping on, keep the story running in your own journal and get back on track as the explorer, pushing forward the boundaries of adventure.

A few weeks passed and an Ethiopian noble rode into town, on his way to patch up a rift with Ras Ali. At dinner one night, the noble offered to take Bell along with him on the next stage of his journey and show him some more of the country. Bell said yes and on 4 April, almost a month to the day after his woodland ambush, he jumped on his horse and was back on his way, leaving Gabriote, still badly wounded, behind him.

Time to speed up. Bell was off again, fording streams, riding past old Portuguese fortresses, feasting on raw beef and honey wine, having a blast. He inspected a bog close to Lake Tana, long acknowledged as the source of the Blue Nile tributary of the great river that flowed on hundreds of miles north through Sudan and Egypt out into the Mediterranean. (Europe’s geographers would have to wait another seventeen years for another wandering Brit to head around 900 miles further south and ‘discover’ the source of the White Nile.) Bell suffered from fevers and severe head pains. At one point he sent for someone to bleed him ‘and after much difficulty a monk was found who undertook to perform the operation’. A servant held Bell in a headlock until the veins stuck out. The monk pulled out a razor, held it against Bell’s forehead and tapped it sharply with a stick. ‘The incision being made, the pressure was removed from my throat, and the blood flowed freely which relieved me much, and I soon recovered my usual health.’ Somewhere along the way, the former wanderer called John Bell, scarred and battered, with a spear wound in between his eyes, a hole in the roof of his mouth and a gash across his forehead, decided this was where he wanted to spend the rest of his life.

On one trip out of the country he met another restless Briton in the port of Suez and persuaded him to come to Ethiopia and share in the fun.

Walter Plowden was another towering young man, buried up to his neck in the British establishment. Branches of his family had records dating back to before the twelfth century, with their own ancestral seat and their own ancestral chapel in Plowden Hall in the heartlands of England, in the Shropshire hamlet of, you guessed it, Plowden.

By the age of 19, he had followed his older brothers, father and grandfather by setting up shop in British India and started making his fortune the respectable and brain-deadening way, working for the banking and trading firm of Carr, Tagore and Company in Calcutta (now Kolkata). But it hadn’t worked out. On the way back to England he met Bell in Suez in 1843, a meeting that, in the words of the Plowden family chronicle, ‘altered his mind’. On the spur of the moment, without funds or planning, he decided to jack it all in, rip up generations of family tradition and seek out his own life in Africa.

So this is where he headed with Bell – to Ethiopia, the perfect place for anyone looking to escape the drudgery of balancing figures and counting stock. For Europeans, this was Abyssinia, one of the purported homelands of Prester John, the mythical medieval Christian priest–king whose vast crusading armies had set out with thirteen golden crosses at their head to challenge the surrounding ‘infidels’. Most people realised his riches, fantastic beasts and other glories were fairy tales stitched together by the chroniclers. But the myth still held. Britons were short of facts about Africa in those days and long on legends.

Abyssinia was also supposed to be the last resting place of the original Ark of the Covenant, the chest designed by God himself for the ancient Israelites to hold the Ten Commandments. Plowden had studied the ancient Ethiopian text the Kebra Nagast, or The Glory of Kings, which set out the story of Ethiopia’s first emperor, Menelik – the son of none other than King Solomon and Makeda, the Queen of Sheba – who, it was said, had brought the Ark to Ethiopia from the Temple in Jerusalem. Who knew what other potent biblical treasures were hiding away in some church in the Abyssinian highlands?

The country was also the home of Rasselas, the fictional Abyssinian prince created by the English writer Samuel Johnson. According to Johnson’s bestselling book The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia, published in 1759, the boy lived a gilded life in a ‘happy valley’ where ‘all the diversities of the world were brought together, the blessings of nature were collected, and its evils extracted and excluded’. The youth and his royal siblings were kept there, apart from the rest of the world, and distracted by an endless succession of entertainments and frivolities until it was their turn to take the throne. At the centre of it all stood a palace where a succession of emperors had buried their gold and jewels in hidden cavities. In the British imagination, the courtly glories of the Ethiopian highlands were part Xanadu, part potential asset.

Bell and Plowden embarked on five years of freewheeling wandering. They found no jewels but made do with several lifetimes’ worth of adventures.

Over time their paths diverged. Plowden dreamed of forging a grand alliance between his new home and his old. Throughout his time in Ethiopia, he sent reports back to London singing the country’s praises, touting its fertility, untapped resources and opportunities for trade. He described how its soil could produce all types of grain, tea, coffee, indigo, spices, cotton, peaches, plums and grapes. After rains, ‘beautiful rivulets meander in all directions, resembling the trout streams of England’. There was iron, gold and copper. Plowden’s letters and journal entries created their own fantasy land to rival Prester John’s. In his hands, Ethiopia transformed into a Merrie Olde jumble of courtly romance. Its tej honey wine flowed like mead. Its songs and singers rivalled those ‘of the old Jongleur or Provençal’, ‘the Highland harper or Irish bard’. Its military hierarchies recalled ‘the feudal times, when the great barons were followed to war by all born on their lands’.

Early on, Plowden travelled back to Britain, surviving a Red Sea shipwreck on the way, and made his case to the Foreign Office in person. His efforts paid off and in January 1848, still in his twenties, Plowden was appointed ‘Consular Agent for the protection of British trade with Abyssinia, and with the countries adjoining thereto’. His official base was back on the Red Sea coast in the sweltering port of Massawa, then an outpost of the sprawling Ottoman Empire. But London, initially at least, encouraged him to keep heading up into the highlands from time to time to keep the lines of communication open and watch over the trade and diplomatic treaty he had finally secured with Ras Ali.

John Bell took things even further. He all but forgot his old land and threw himself into his home. He wore Ethiopian clothes and, in the years that followed, married an Ethiopian noblewoman, Woizero Warknesh Asfa Yilma, and started a family. John became Yohannes as he moved on from his early unsatisfactory encounter with Ras Ali and effectively signed up as one of his generals, waging Ras Ali’s wars, charging around the land and leaving nineteenth-century Britain, with all its relentless clanking, steam-powered churn, far behind him.

There was a tricky interlude when it turned out that Bell had backed the wrong man. This was a particularly tumultuous era in Ethiopian politics known as the Zemene Mesafint – a name that has been translated as both the Age of Princes and the Age of Judges, after the era described in the Old Testament Book of Judges when ‘there was no king in Israel [and] every man did that which was right in his own eyes’. Ethiopia’s ancient line of Solomonic leaders had disintegrated into a succession of puppet emperors, and the real powers in the land were the princes, the Rases, who battled endlessly over influence and territory.

Ras Ali, with Bell fighting at his side, was defeated at the Battle of Ayshal on 29 June 1853 by an emerging power – Ras Ali’s own rebellious son-in-law, a minor noble turned shifta turned militia leader known at the time as Kasa, the man who would go on to become King of Kings Tewodros II, the future father of our prince.

Ras Ali fled and, after a few minor skirmishes, faded from history. Bell, as the story goes, took refuge in a church after the defeat ...