Light is the freely available messenger that allows us to sense remote objects in our environment without the need to interact with them directly. This is the modern view of vision that began with the Persian philosopher and physicist, Alhazen (or more properly, abu-‘Ali A1 Hasen ibn A1 Haytham, 965–1039). Vision would have been easier to understand if the older view that light is emitted by the eye as a type of feeler, had been correct. Laser range finders work on this principle and are at present the only flawless way of measuring depth with light images. In the same way the colour of a surface, i.e. its reflectance, is easily computed if you know the position and nature of the source of light and the orientation of the surface.

The more difficult modern view, however, is the accepted version, and much of the rest of this essay will be concerned with the effects of unknown sources of light on an unknown arrangement of surfaces in the scene. Light is an uncertain messenger: It is not like a nice steady weight that can be reliably measured; it is a stream of random and largely independent particles, the photons, each of which has its own characteristic energy. The rate of arrival of photons at the eye is variable; we call this photon noise, and the variability depends on the mean rate. The mean rate of arrival is the intensity of the light. It is usually expressed as intensity per unit area, illuminance, which is similar to luminance, the intensity per unit area of emitted light. To avoid these cumbersome photometric units, I shall use the term grey-level to refer to the illuminance of the retina at an arbitrary small area.

In vision, measurements of the intensity of light sources are not of interest.

If one knows all these details, then the grey-level at that particular point in the image can be calculated. The problem in vision is that these processes cannot be reversed: The grey-level on its own does not distinguish between the various factors causing it. In principle, any given retinal image could arise from an infinity of possible scenes, including a flat uniform surface illuminated by a patterned light source (the principle behind slide and cine projection). In practice, of course, we are very rarely faced with any operational ambiguity. The visual system generally manages to make a choice concerning the scene, and it is usually correct. This choice is made on the basis of assumptions concerning the most likely types of scenes. The scenes that we inhabit are generally constrained.

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS OF VISUAL PROCESSING

Vision exists so that we can see what to do. Ultimately visual tasks require a full scene description in terms of the visible bodies, their shapes and sizes, their positions and motions, and their surface colours and markings. We are a long way from understanding how this is done, but we can, for simplicity’s sake, break the process down into a number of sub-processes.

Marr’s analysis of the architecture of low-level vision is currently the most widely used (see Marr, 1982), even though there are doubts about many details. Marr divided the process of vision down into three sub-processes, each of which delivers a representation for the next sub-processes. The three representations may be summarized as:

Primal Sketch: | A two-dimensional representation of significant grey-level changes in the image. |

2.5D Sketch: | A partial three-dimensional representation recording surface distances from the observer. |

Solid-model based representation: | A fully worked out volumetric representation of bodies in the scene. |

There are significant concepts in this simple framework. A representation is a symbolic descriptor. It builds a description from a finite alphabet of primitive symbols (such as “edge”, “bar”, “corner”), each having an associated attribute list (recording: size, orientation, contrast, for example) and a grammar or set of rules that will exactly and exclusively generate all valid sentences or scene descriptions. A sketch is the process that produces, analyses, and represents the data.

This essay is concerned only with the Primal Sketch, the reason being that there are several psychophysical and psychological studies that indicate that the Primal Sketch is far from dull and straightforward. Whereas Marr tended to regard it as an inflexible, automatic, memoryless process producing something rather like an edge map, I shall describe some evidence that points to high-level control and memory very early in the process. It will be argued that many of the visual attention phenomena have their roots, trunk, and some branches in the Primal Sketch, and that there is a particularly striking simplicity to the machinery that belies a wonderfully rich diversity of function.

Output Requirements of the Primal Sketch

Why have a Primal Sketch? Why not just have a 2.5D Sketch as the first stage? The motive for the existence of a separate Primal Sketch in Marr’s work is relatively simple. The image itself has a great deal of information that is irrelevant to the 2.5D Sketch, and the Primal Sketch can be used to provide an economical representation. A second reason is that many of the computational problems in the 2.5D Sketch, such as stereomatching, would be hopelessly confounded by grey-levels rather than, for example, edge tokens. To these two reasons, one can add the obvious statement that many visual processes require a representation of the grey-level changes, not a 2.5D Sketch. Imagine how text would have to be written if we had no access to a Primal Sketch.

It seems reasonable to require that the Primal Sketch squeeze as much meaningful information out of the image as possible. Only part of this will be relevant for the 2.5D Sketch. One ultimate goal of vision is an understanding of the layout of bodies in three-dimensional space. The term body is used here to refer to a compact solid mass that remains coherent, at least over the time scale of perception. Our perceptual understanding of the scene is going to be in terms of objects, which do not necessarily correspond to bodies. A tree in winter is one body, but may be represented as a hierarchy of objects: its overall bulk, the trunk, and largest boughs, or individual twigs. The term object refers to a unit of perception. Bodies cause the input to vision; objects cause behaviour that is the output of vision.

The main task of the Primal Sketch is therefore to extract from the image all the relevant information about the layout and character of visible surfaces and to construct a convenient representation. Ideally the representation at this level of processing will be used in turn for all other subsequent processes, and so it must be a rich source of information. The Primal Sketch representation will be used to construct a depth representation, using for example information about occlusions, shading, texture gradients, and disparity differences (if there are two Primal Sketches, one per eye). The interesting parts of images concern the locations where surfaces become occluded, especially where surfaces occlude themselves by turning away from the observer, and the locations where surfaces bend even though they may remain visible, such as sharp creases.

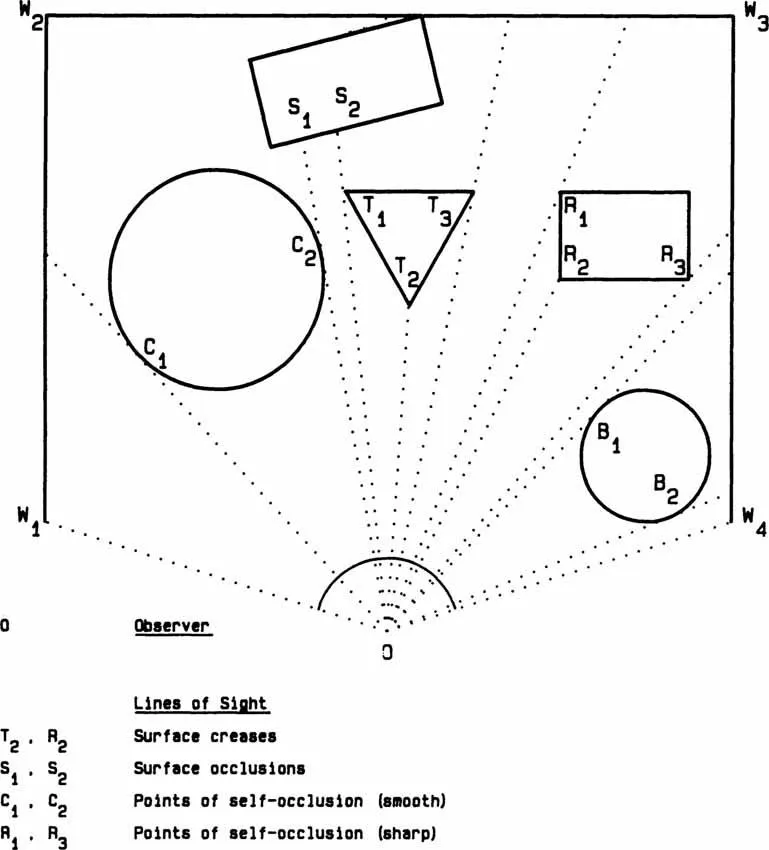

Figure 1.1 shows a ground plan for a scene and marks the position of an observer, O. The scene has three walls, W1–W4, within which there are five bodies: an upright circular cylinder, C; two boxes with rectangular crosssections, S, R; an upright block with triangular cross-section, T; and a sphere, B. Various lines-of-sight from the observer are also shown and each reaches a point of particular interest, which we might require the Primal Sketch to identify. For example, the cylinder occludes itself at points C, and C2. There is no sudden change in the character of the cylinder surface here, but to the observer, these two points will appear to be distinctive as the edges of the cylinder because there is a discontinuity in surface depth from the observer. Very often such occluding edges also correspond to discontinuities in surface orientation, i.e. creases or comers, such as points R1, R3, and W1. Creases and comers can also be imaged so that they do not correspond to the occluding edges of objects, as at points T2 and R2.

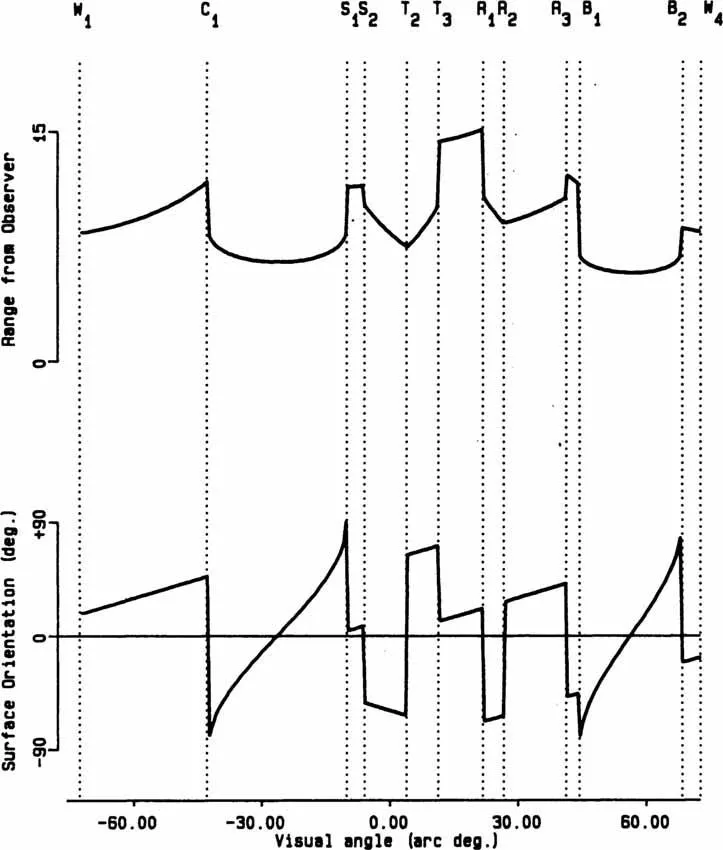

The top of Fig. 1.2 shows the equivalent range or depth map for the observer at point O. This might be a useful precursor to a full reconstruction of Fig. 1.1 because it records the distance from O to the nearest reflecting surface in each direction. Figure 1.2 also shows the variation in the orientation of the visible surfaces in the scene with respect to the observer at O. Surface orientation is important because it determines the surface luminance: Surfaces that are head-on to the source of light have a higher illumination level per unit surface area than those oblique to the source. Notice that the lines-of-sight from the observer to occluding edges correspond to sudden changes in range from the observer and sometimes also in orientation. The lines-of-sight to creases, such as T2 and R2, correspond to abrupt changes in surface orientation, but not in range.