eBook - ePub

The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss

About this book

The idea that changes in biodiversity can impact how ecosystems function has, over the last quarter century, gone from being a controversial notion to an accepted part of science and policy. As the field matures, it is high time to review progress, explore the links between this new research area and fundamental ecological concepts, and look ahead to the implementation of this knowledge.

This book is designed to both provide an up-to-date overview of research in the area and to serve as a useful textbook for those studying the relationship between biodiversity and the functioning, stability and services of ecosystems. The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss is aimed at a wide audience of upper undergraduate students, postgraduate students, and academic and research staff.

This book is designed to both provide an up-to-date overview of research in the area and to serve as a useful textbook for those studying the relationship between biodiversity and the functioning, stability and services of ecosystems. The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss is aimed at a wide audience of upper undergraduate students, postgraduate students, and academic and research staff.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss by Michel Loreau,Andy Hector,Forest Isbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Biodiversity and Ecosystems: An Overview

1

Biodiversity Change: Past, Present, and Future

Andy PURVIS1,2 and Forest ISBELL3

1 Natural History Museum, London, UK

2 Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot, UK

3 University of Minnesota, St. Paul, USA

1.1. Setting the stage: difficulties of documenting, understanding, and communicating biodiversity change

The IPBES Global Assessment of biodiversity and ecosystem services concluded that transformative change to the global socioeconomic system is necessary if biodiversity loss is to be stopped (Díaz et al. 2019). As soon as it was launched, it faced concerted pushback from what might be termed “extinction denialists” (Anon 2019, Lees et al. 2020). These critics used a range of tactics in an effort to undermine the credibility of the evidence presented in the Global Assessment, presumably in order to maintain the (for them) comfortable status quo. They variously conflated different measures of biodiversity change, cherry-picked counterexamples to general patterns, denied that change is taking place, argued that change is always taking place and therefore there is nothing to worry about, emphasized uncertainties, argued that biodiversity loss was essentially a historical rather than current issue, argued that some of the drivers of biodiversity loss were actually solutions, and even alleged misuse of data. Although their arguments were at best disingenuous, these “doubters for hire” were able to gain some traction because of the inconvenient truth that quantifying biodiversity change and understanding the reasons for it are both surprisingly difficult. Why?

One important reason is the sheer breadth of the concept of biodiversity. As defined in the Convention on Biological Diversity (United Nations 1993), it is “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.” This broad definition encompasses:

- – all measures of the variety of life in an area, within and across all taxonomic groups, including their traits and their interactions with each other and their abiotic environment; this is termed α-diversity;

- – how all of these change as one moves to another area; this spatial turnover is known as spatial β-diversity;

- – assessment for all sizes of area, from a single point to the entire globe; this aspect of scale is known as spatial grain.

The inclusivity of this definition of biodiversity may have helped the rapid adoption of the term by researchers in conservation and ecology – whatever we study, it is covered – but it also contributes to at least four serious problems that hamper the development of simple, clear messages about biodiversity change and their communication to policy makers or the broader public.

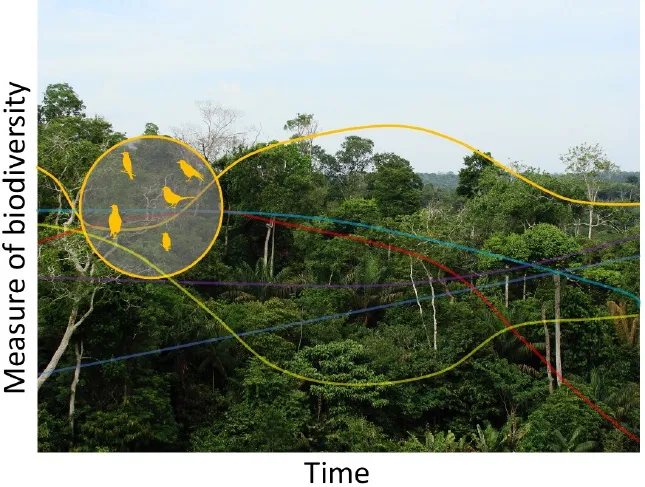

First, measuring biodiversity as a whole – even for the smallest area – is not practically possible. Researchers therefore routinely and necessarily take shortcuts, using subsets of biodiversity (e.g. the birds seen in daylight in a two-week period of the summer) as proxies for the whole, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. The subsets are often chosen for reasons of convenience or even habit rather than because evidence shows them to be representative of biodiversity more broadly. This assumption of representativeness is so deeply implicit that many papers do not seriously consider the possibility that it is wrong. It usually is wrong: taxonomic groups differ widely in their responses to drivers of change (Lawton et al. 1998) and temporal trends even within the same region (Outhwaite et al. 2020). Alternatively, subsets may be chosen not because they are representative but because they are unusually sensitive to environmental change. The traditional use of indicator species is to monitor for changes in the environment, rather than in biodiversity (Siddig et al. 2016), so a combined temporal trend for such species may suggest much more rapid biodiversity change than would be seen from a representative set of species.

Figure 1.1. Different taxonomic or ecological subsets of biodiversity may change differently over time. In this schematic, monitoring birds gives a time series of estimated biodiversity (orange line) that differs from those that other groups of species would give (other lines). Rainforest photograph: Ben Sutherland (CC BY 2.0). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/loreau/biodiversity.zip

Second, biodiversity data are even less comprehensive than this use of shortcuts implies. For example, while ~1.5 million extant species of animals have been named, estimates of the true total number range from 3–100 million (Caley et al. 2014). Our biased knowledge makes it hard to generalize to biodiversity as a whole. We know more about large species, terrestrial species (especially birds), and species in developed countries than we do about small species, marine species, and species in emerging economies or developing countries (Hortal et al. 2015; Meyer et al. 2015). The situation is worse still for biodiversity in the past. At the time of writing, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database (www.gbif.org) holds nearly 1.5 billion georeferenced occurrences of species whose year of observation is known; fewer than 4% are from before 1970. Very few high-quality ecological time series cover more than a few decades (Magurran et al. 2010), and very few monitoring schemes began before the 1970s. Moving to fossils, most extant animals and plants are not known from the fossil record; most extinct species never fossilized; tropical rainforests are particularly bad environments for fossilization; most fossil locations have temporal gaps in the record and permit only approximate dating; and none of the hierarchical levels of classification (species, genus, etc.) mean the same thing for fossils as in the present day (Kidwell and Flessa 1996; Forey et al. 2004; Purvis 2008).

Third, as discussed in Chapter 2, there are uncountably many ways of quantifying the biodiversity present in a given sample of organisms, and this number rises further when spatial turnover and different spatial scales are considered (McGill et al. 2015). Although frameworks are emerging to organize this diversity of diversity measures (see Chapter 2) (Pereira et al. 2013), consolidation is far from complete. Even if all researchers agreed what taxa to sample, we would not agree on how to measure them. It follows that there are also uncountably many ways to quantify biodiversity change over time. The combination of very many possible measures and relatively little temporal data, especially over long time periods, makes it very hard to bundle all the different measurements together into a coherent tapestry showing change over time.

Fourth, most laypeople’s concept of biodiversity is much narrower than the very broad Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) definition – often the number of animal and plant species (Bermudez and Lindemann-Matthies 2020) – setting up obvious communication problems.

Despite these difficulties, there is unambiguous evidence that biodiversity has changed over time both naturally and as driven by human-caused pressures. The next three sections briefly sketch some of this evidence, followed by a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction

- PART 1 Biodiversity and Ecosystems: An Overview

- PART 2 How Biodiversity Affects Ecosystem Functioning

- PART 3 How Biodiversity Affects Ecosystem Stability

- PART 4 How Biodiversity Affects Human Societies

- PART 5 Zooming Out: Biodiversity in a Changing Planet

- List of Authors

- Index

- End User License Agreement