eBook - ePub

Community of Peace

Performing Geographies of Ecological Dignity in Colombia

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Achieving peace is often thought about in terms of military operations or state negotiations. Yet it also happens at the grassroots level, where communities envision and create peace on their own. The San José de Apartadó Peace Community of small-scale farmers has not waited for a top-down peace treaty. Instead, they have actively resisted forced displacement and co-optation by guerrillas, army soldiers, and paramilitaries for two decades in Colombia's war-torn Urabá region. Based on ethnographic action research over a twelve-year period, Christopher Courtheyn illuminates the community's understandings of peace and territorial practices against ongoing assassinations and displacement. San José's peace through autonomy reflects an alternative to traditional modes of politics practiced through electoral representation and armed struggle. Courtheyn explores the meaning of peace and territory, while also interrogating the role of race in Colombia's war and the relationship between memory and peace. Amid the widespread violence of today's global crisis, Community of Peace illustrates San José's rupture from the logics of colonialism and capitalism through the construction of political solidarity and communal peace.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Community of Peace by Christopher Courtheyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

RADICAL PERFORMANCE GEOGRAPHY

Embodying Peace Research as Solidarity

An anticolonial geography of peace requires an appropriate methodology that integrates critical analysis and political action. In agreement with Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (2012), “there can be . . . no theory of decolonization, without a decolonization practice” (100). If I intend to create and live in a just world, then I have to enact critical theory through my research practice. Combining critical spatial theory and performance ethnography, I call my methodology radical performance geography.

The first component is structural analysis rooted in critical and radical human geography, feminist geopolitics, critical race theory, and decoloniality, in order to understand the context in which peace movements take place. Informed by a Marxist critique of capitalism (Marx 1976), critical development studies (Escobar 1995), and world-systems analysis (Wallerstein 2004), critical geography adds an explicitly spatial lens to critical theory’s analysis of states, capitalist core–periphery relations, neocolonialism, and social movements (Harvey 2001, 2012; Gregory 2004; Routledge 2008). Meanwhile, radical geography considers the spatial dynamics of alternatives outside dominant systems, such as noncapitalist economies (Gibson-Graham 2006) and anarchism’s non-statist politics (Springer 2012). Building from critical geography, the subfield of feminist geopolitics attends to the militarization-state-resistance nexus by foregrounding the embodied practices of those experiencing or resisting war, which reveals the interdependence of global, national, local, and personal processes of power (Dowler and Sharp 2001; Fluri 2011; Koopman 2008; Mayer 2004). Moreover, critical scholarship on race attends to how certain populations are marked as “less than human” and struggle for liberation (Fanon 2008; Gilmore 2002; Goldberg 2009), with the subfield of black geographies adding a spatial lens to the places and practices of blackness (McKittrick and Woods 2007). This complements the feminist approach for an intersectional analysis of the multiple violences that structure the modern world-system as well as subversion to violence through spatial and political practice. The framework of decoloniality situates these processes of oppression and liberation within the global history and logics of patriarchal and racist power in the modern-colonial world (Quijano 2010; Mignolo 2010; Lugones 2010; Dussel 1985). Critical theory is thus essential for both deconstructing how phenomenological conditions are structured by sociohistorical power relations and creating emancipatory alternatives to them (Gómez Correal and Pedraza 2012). This book therefore highlights the Peace Community’s everyday practices of peace, which are understood in relation to broader processes of global violence and struggle, such as today’s resistance by racialized peoples to state-corporate enterprises’ land grabbing in new resource frontiers.

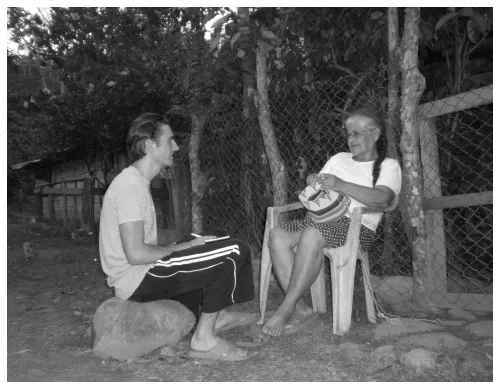

My second methodological point of departure is critical performance ethnography, which Soyini Madison (2012) deems “critical theory in action” (16). Understanding the performative aspects of research is particularly crucial for geographers, because we not only write about and analyze space; we also perform and create space. As a performance geographer, I use the written word as well as my body in space as a mode of inseparable investigation, analysis, and presentation. My work is critical by rejecting orientalist ethnography’s complicity in conquest and the pretension of an outsider observing “over the shoulders” of a research “subject-object” (Conquergood 2002). As a geographer I am inevitably a participant in the construction of particular forms of peace through my presence and publications. I take such political stakes seriously by highlighting community members’ voices and merging my analysis with the critical theory necessary to fully grasp their praxis. It is essential to link ethnography with critical theory in order to situate local processes within global relations of power that structure and are structured by them. However, this works both ways, where ethnographic action research is a means to put academic theory into practice. Therefore this is performance geography in that I recognize how my body as a researcher marching in a community mobilization or interviewing government officials performs international solidarity with peace communities and is interpreted as such by both social movement organizations and armed actors. As part of the global climate and racial justice movement, my intent is to utilize the fieldwork process of research itself as a radical political act against neocolonial militarization by increasing the safety and visibility of racialized communities struggling for alternatives to the social and ecological violences at the root of today’s global crisis. Moreover, I understand the interview not as an extraction of data but as a performative space of dialogical knowledge production; the back-and-forth conversation of a semi-structured interview allows for continual reflection and clarification as well as the formation, critique, and crystallization of theory (Madison 2012; Pollock 2005). I present my experiences and Peace Community voices with poetic transcriptions and staged performance pieces toward more embodied renderings of ethnographic research and political struggle; these put the body and the word in motion for innovative presentations to a broad array of fellow academics, research interlocutors, and government and social movement actors.1 All of these methods reflect a quest for “dialogical performance” between researchers and interlocutors (Conquergood 1985) toward the coproduction of knowledge against oppression.

Such deeply reflexive, embodied, and collaborative work calls attention to the political implications of our presence and publications as researchers. A dynamic toolkit of performative methods offers creative ways of conducting fieldwork and presenting findings that complement written work for ethical and effective scholarship. Radical performance geography therefore integrates critical geographical theory and performance methods into a comprehensive methodology to not only analyze places but also more consciously embody and produce spaces of peace through research. In this chapter, I detail my methodological process.

SOLIDARITY

I emphasize radical in the naming of my methodology for full disclosure about what drives my theory and politics. Personal experiences and political leanings can limit or enhance our abilities to interpret or comprehend particular phenomena and political projects. For instance, during a speaking tour in the United States, Peace Community leader Jesús Emilio Tuberquia (2011) was asked about the role academics can play in their process. He responded by stating that such outsiders often misunderstand: “They write in their summaries that we are anarchists. No, we are a project of life.” Reflecting on critiques I have heard over the years of the Peace Community as a courageous but still “parochial” or “unrealistic” alternative, I sense that researchers and accompaniers primarily focused on the modern state system of electoral representation and realpolitik geopolitics have difficulty interpreting the Peace Community’s practice as more than a limited retreat within the system. Given San José’s autonomous peace praxis, I argue that to fully appreciate the depth, significance, and possibilities of the Peace Community, we have to approach it from the perspective of a radical anti-systemic politics (Wallerstein 2004) that exceeds what seems politically and socially “realistic.”2 Indeed, much of my subjective political formation took place as an accompanier in the Peace Community, exposing me to such a politics of “rupture” and convincing me to take such alternatives to electoral politics and armed struggle seriously.

Research with a community in the middle a war zone such as San José de Apartadó is often conditioned on solidarity with the organization in question, for security or other reasons. In line with what bell hooks (1984) calls “Sisterhood” in the feminist movement and Sally Scholz (2008) calls “political solidarity,” I use the term solidarity to refer to collaboration across difference that challenges oppression, which is rooted in a political commitment to struggle and transformation. What is commonly referred to as the solidarity movement in the United States is rooted in alliances (often by white people) with those excluded from the national body politic: racialized people, undocumented migrants, resistance movements in the Global South (Russo 2019). Sara Koopman (2011) calls alliances that strategically use geopolitical networks to impede violence against communities in resistance “alter-geopolitics.” Depending on the nature of the interaction, such solidarities can reproduce white privilege and saviorism (Boothe and Smithey 2007; Koopman 2008) or foster a dialogical performance among people committed to justice and dignity (Koopman 2011). Anticolonial solidarities must be a transformative process that politicizes, creates new subjectivities, and fosters innovative political strategies and tactics (hooks 1984; García Agustín and Jørgensen 2016; Featherstone 2012).

Attention to the dialogical performance of solidarity also helps elucidate the dynamics of ecological dignity in Peace Community food sovereignty initiatives and Campesino University trans-ethnic networks, but my focus in this chapter is on the dynamics between communities in resistance and allies and researchers. Being in solidarity does not mean in total agreement with a counterpart’s organizational strategy. Notwithstanding, I wish to disclose that my objective here, as an outsider, is not to provide a comprehensive account of all of the internal workings of the Peace Community. Similar to Arturo Escobar’s (2008) work with the Colombian Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN, Black Communities Process), I am a non-member and view my role as a scholar to explain San José de Apartadó’s significance toward evaluating our current conjuncture and strategies of social transformation, rather than meticulously critiquing the Community’s internal dynamics. The appropriate space for such dialogues is directly with Peace Community members and their Internal Council, rather than through this book. Here I agree with Anna Tsing (2005): “My ethnographic involvement with activists taught me the restraint of care: There are lots of things that I will not research or write about. I do not mean that I have whitewashed my account, but rather that I have made choices about the kinds of research topics that seem appropriate, and indeed, useful to building a public culture of international respect and collaboration” (xii). Such ethical protocols are essential to protect against the potential harms of research through dialogue, care, and discretion, without compromising one’s commitment to critical analysis.

1.1. Dialogical performance: Interview with Doña Brígida González in San Josecito. Author photo.

EMBODYING PEACE RESEARCH IN AND BEYOND THE FIELD

As a geographer of peace who is a former international accompanier in Colombia, I am situated as an active participant in the Peace Community’s process that builds from my historical relationship with them. I first arrived in San José de Apartadó to serve as a protective accompanier, working for seventeen months, from 2008 to 2010, with what was then the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Colombia Peace Program. This program later became the independent organization FOR Peace Presence, where I served on the board of directors from 2013 to 2019. With the exception of 2015, I visited San José de Apartadó every year from 2008 to 2020 and have spent a total of just under two years (twenty-three months) there. This is part of the six years I have studied and worked in Colombia for more than the past decade.

To inquire into people’s ideas of peace, memory, and territory, I conducted sixty-eight semi-structured interviews across Colombia between 2011 and 2018. Reflective of local practices of communal debate and decision making, ten of these were group interviews involving two to five people concurrently. In the Peace Community I interviewed a total of twenty-seven members from eight of their eleven settlements, and I had repeated interviews with six of these members. These interviewees included eleven women and sixteen men of various ages. Some were founding members of the Community while others had joined only in recent years. For additional perspectives, I interviewed twenty-one members of other Colombian communities and social movement organizations, four army and police officers, and seven protective accompaniers, for a total of sixty-nine people interviewed altogether.

Adapted as appropriate for the particular interviewee or group, my questionnaire included the following: How do you define peace? How do you understand the roots of the war? What is your perspective on the state–FARC peace talks? Why do you commemorate history or victims in the ways that you do, and how do those memory practices affect your organizational process? What is the relationship between memory and peace? What do land and territory mean to you, and how do they relate to peace? What is your relationship with state agencies as well as other Colombian and international organizations? What is international accompaniment, and how do you evaluate it? How have your organization’s strategic practices emerged or changed over time? What have you learned from other organizations, and what lessons can you offer for other peacebuilding initiatives?

Interviews can also be a form of political accompaniment. One visit to an army base was particularly memorable. At the beginning of a trip to Urabá in September 2013, I emailed and faxed a letter to the region’s military authorities to announce my arrival to the region, copied to my research sponsors and collaborators. This followed the protocol of international accompaniment organizations, who send such advisory letters to law enforcement agencies and the diplomatic corps to increase visibility of their movements and the safety of those they accompany. When I went to the military base to schedule an interview in April 2014, I was able to arrange a meeting on the spot with one of the commanders. I remember reflecting on how easy it was to get access, given my position as an international researcher and the power that connoted; it felt even easier to get a meeting as an academic than it was while I was an accompanier in frequent contact with these officers. I brought my introduction letter with me and presented it to the people I asked for interviews. After glancing over it, one officer passed the letter off to a lower-ranking official for her to take into another room and review. He asked me about my time as an FOR accompanier, which he had seen indicated on the letter, and proceeded to call the current team’s cell phone to ask if they knew me. When the lower-ranking officer returned, he asked her what the letter said, and she responded that it explained what I had verbally told them, that I was there from the University of North Carolina doing research about peace and wanted to speak with them. We continued to talk, until he suggested I interview other officers within the brigade, which I did. I interviewed Colombian army and police officers not only to include their perspectives in this geography of peace, but also to disclose my presence in the area and embody my political network as a form of potentially dissuading attacks against the Peace Community.

1.2. Fieldwork sites in Colombia. Map by author.

To complement my interview inquiries about how people defined peace, I investigated the embodiment of peace by witnessing daily practices and events. Recognizing the ways my body projected international solidarity, I understood this as co-performative action research. In addition to San José de Apartadó, I visited artisanal gold miners in Caldas; Afro-Colombian community associations in Chocó and Bolívar; campesino organizations in Sucre, Bolívar, and Caldas; land restitution activists in Antioquia; community organizers and urban Hip Hop youth collectives in Medellín; youth conscientious objectors in Medellín and Bogotá; nonviolent reconciliation trainers in Barranquilla; as well as trade activists, human rights defenders, state crimes victims’ organizations, and representatives of the Colombian Congress in Bogotá. In multi-organization gatherings in San José de Apartadó and at university events in Colombia and the United States, I also interacted with representatives of indigenous communities from Cauca, Chocó, Cesar, and La Guajira; Afro-Colombians from Cauca; campesino communities from Quindío and Cauca; and victims and human rights organizations from Bogotá. Such encounters also served up many informal yet insightful conversations about peace, memory, territory, race, and politics.

To complement the Peace Community experience, this book cites personal statements as well as the public or written works of a variety of other organizations. Interactions with organizations such as the Red Juvenil de Medellín (Youth Network of Medellín) and Tejido Awasqa Conciente (the Conscious Cultural Weave collective, sometimes written as Tejido Awasqa Cultural and commonly referred to as simply Awasqa) provided urban youth perspectives on peacebuilding. Presentations and publications by Tierra Digna—Centro de Estudios para la Justicia Social (Land of Dignity Research Center for Social Justice) were particularly useful to understand the context of Colombian economic, environmental, and military policies. I also draw from evaluations of the government–FARC peace process by victims movements such as Hijos e Hijas por la Memoria y Contra la Impunidad (Sons and Daughters of Memory and Against Impunity) and Movimiento de Víctimas de Crímenes de Estado (MOVICE, Movement of Victims of State Crimes); land restitution activists from Tierra y Vida (Land and Life), originally founded as the Asociación de Víctimas para la Restitución de Tierras y Bienes (ASOVIRESTIBI, Association of Victims for Restitution of Land and Assets); the campesino organization in Sucre known as Sembrandopaz (Planting Peace); as well as Afro-Colombian organizations such as Consejo Comunitario Mayor de la Organización Popular Campesina del Alto Atrato (COCOMOPOCA, Community Council of Campesino Popular Organization of the Upper Atrato river region) and Consejo Comunitario Mayor de la Asociación Campesina Integral del Atrato (COCOMACIA, Community Council of the Integ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Prologue

- Introduction. Peace Communities: Ecological Dignity as Anticolonial Rupture

- Chapter 1. Radical Performance Geography: Embodying Peace Research as Solidarity

- Part I. What is the Peace Community?

- Part II. What is Peace?

- Part III. What is Politics?

- Epilogue

- Appendix: Historical Timeline

- Notes

- References

- Index