![]()

PARISH DISTRIBUTION AND SIZE OF PROPERTIES

JAMAICA IS LOCATED IN THE TROPICAL ZONE and has a land mass which includes large areas of highland interior, consisting primarily of peaks and plateaux, with the physical and climatic conditions ideal for coffee culture.1 In the early nineteenth century certain parishes became more synonymous with its cultivation; as planters in Jamaica sought to locate their plantations in areas with the topographical and ecological conditions most suited for their purpose. Up to the 1760s, when coffee for export was not as significant as it was to become by the early nineteenth century, its production was confined largely to the foothills in the parish of St Andrew.2 With the rapid expansion in the 1790s, plantation settlements were extended throughout the Blue Mountains and the hilly interior of the eastern and other parishes, resulting in coffee production for export being evident in almost every parish (as they existed then) by the early nineteenth-century plantation Jamaica.3

Concerned about the threat of Maroon attacks on white settlers in the mountainous interior of the island, the government took note of this rapid expansion. It documented that by 1800 at least twenty-two new coffee-producing properties had been established, with more being planned, throughout the mountainous regions in the parish of St George (part of present-day Portland) as well as in the area that began north of the mouth of the Bautima River and extended through to where a new road had been cut from Swift River to Silver Hill. Coffee properties were also established between the East Spanish River on the west and Swift River on the east.4 It was noted that properties had also recently been established in St Thomas-the-East, on a significant portion of land well adapted to the cultivation of coffee in the upper part of the Blue Mountain Valley, as well as in the mountainous areas of St David, where a number of settlers were engaged in the cultivation of coffee.5Expansion of cultivation was also evident in the central parishes, in the Mocho Mountains in Clarendon6 and the Cedar Valley Mountains in St Catherine, where coffee and all kinds of provisions were being produced.7 In the western parish of St Elizabeth, the district of Nova Scotia, which lay between Mile Gully and the Black Grounds, as well as the area known as Siberia, between Mile Gully and Quashies River Barracks, were also established in coffee cultivation.8

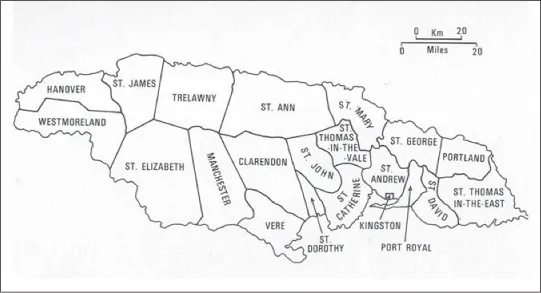

Plate 1.1. Map of the island of Jamaica, divided into counties and parishes, 1794. (Courtesy of the National Library of Jamaica.)

Plate 1.2. Map of Jamaica showing parishes, 1814–1834. (Higman, Slave Population and Economy, xxi.)

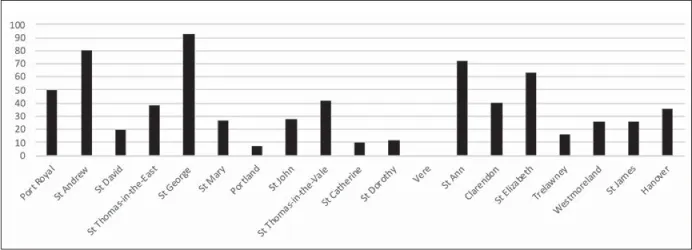

Figure 1.1. Parish distribution of coffee-producing properties, 1799

Source: Compiled from Further Proceedings of the Honourable House of Assembly, appendix to Evidence no. 9 (1800).

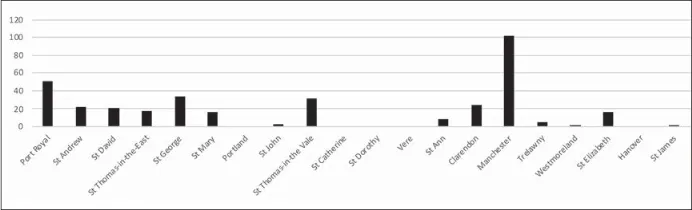

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, two distinct regions, in the eastern and central parishes of the island, emerged as predominantly coffee-producing areas. In the eastern section these included the parishes of Port Royal, St Andrew, St David, St Thomas-in-the-East, St George, St Mary, Portland, St John and St-Thomas-in-the-Vale. These parishes together contained 385 properties, representing 57 per cent of the 686 then in existence. In St Andrew, St David, St Thomas-in-the East and St George (which is today the western section of the parish of Portland, from Buff Bay through Newcastle, Shirley Castle and Fruitful Vale), 231 properties were to be found. The other region associated with coffee production in the early nineteenth century encompassed the central parishes of St Ann and Clarendon and the more easterly part of St Elizabeth, which together accounted for 175 properties. St Ann and St Elizabeth, while initially containing numerous coffee-producing properties in the 1790s, eventually became minor producers; the majority were pen-keeping properties devoted to livestock rearing.9 This was a result of the redrawing of parish boundary lines in 1814 to create the parish of Manchester, which was carved out of sizeable portions of land formerly contained within the parishes of St Ann, St Elizabeth, Clarendon and Vere. By the 1820s Manchester had the largest number of coffee plantations, largely on account of abandonment of properties in some of the eastern parishes, as a result of soil erosion hastened by a great storm in October 1815.10

In Manchester some of the properties combined coffee production with livestock rearing, which was possible given the varied topographical features of the parish. For example, Higman tells us that Grove Place plantation, which contained 3,493 acres, carried 575 head of livestock, but its most important source of revenue came from coffee exports, which accounted for 74 per cent of its total income in 1832.11 The raising of livestock as working animals on coffee plantations would have been important for coffee processing, given the heavy reliance on animal-powered mills in the central parishes of Manchester and St Elizabeth, where there were fewer rivers and streams from which to operate water-powered mills.

Figure 1.2. Parish distribution of coffee-producing properties, 1836 Source: Shepherd, Livestock, 45, table 2.6.

In 1799 a fair number of properties were also to be found in Trelawny, Westmoreland, St James and Hanover. These parishes formed the main sugar-producing belt of the island, but they also contained mountainous areas suitable for successful coffee cultivation. The environmental conditions in these areas may not have been ideal, but landholders clearly saw the opportunity to convert idle land to coffee production in order to take advantage of unusually high prices on the international market in the late eighteenth century. By the 1830s, however, there had been a significant fall-off in the numbers, indicating the marginality of those properties.

Successful coffee cultivation requires a cool climate. Where conditions are too hot and dry, the plant is liable to become parched. However, P.J. Laborie, a French creole émigré, warned that in too-cool conditions the plant would grow too rapidly “into a vast luxuriance of wood, and then yield very little fruit”. The plants were also liable to lose their leaves and branches. Laborie therefore suggested an elevation “above the middle of the mountain”.12 This advice is supported by Alex Haarer, who notes that elevations above 5,000 feet are generally too cold for coffee culture, although Francis Thurber points out that in drier areas, coffee can thrive as high as 6,000 feet above sea level.13 Normally it is best cultivated between 1,500 and 4,500 feet above sea level, though in British Guiana, coffee plantations were established along the coastal areas of the Demerara and Berbice Rivers and grown alongside sugar and cotton.14

Altitudes between 3,000 and 5,003 feet above sea level are associated with temperatures regarded as ideal for the cultivation of coffee arabica. Such temperatures result in the shrubs’ remaining healthy, producing good crops every year without excessive exhaustion of the plants and fluctuations in their yield. Also, pests and diseases are minimal at such altitudes.15 In Jamaica, plantations were established at these altitudes, though coffee was sometimes grown at lower levels. In the eastern section of the island, plantations were to be found on the Blue Mountains range at altitudes of 5,003 feet and above, while others could be found on lower ranges.16Arntully, Radnor and Springfield, which were among the largest coffee plantations in the industry, were in St Thomas-in-the-East (present-day eastern St Thomas, in the Manchioneal and Hector’s River areas) and St David (present-day western St Thomas), were established at elevations between 3,000 and 5,003 feet. Radnor’s coffee factory were located two miles shy of Blue Mountain Peak, which has an elevation of 7,402 feet. The Mavis Bank coffee plantation in St Andrew was at an elevation of 2,500 feet.17

In the central section of the island, in the parish of Manchester, plantations were to be found on plateaux which ranged between 1,000 and 3,000 feet in altitude. In that parish, the May Day and Don Figuero Mountains rose to elevations of between 2,000 and 3,000 feet. Huntly, Grove Place, Knockpatrick and Rose Hill coffee plantations could all be found within this range. In 1820 Brumalia coffee plantation occupied gently sloping mountains which ranged between 2,000 and 2,250 feet, in an area west of the emerging town of Mandeville. Waltham plantation occupied lands to the south of the town, while Swaby’s Hope plantation was located on lands at the edge of Spur Tree. In Clarendon, coffee was produced in the Dry Harbour Mountains, which ranged between 2,000 and 3,000 feet above sea level.18

In Hanover, Westmoreland, St John and Vere, though primarily sugar-producing parishes, mountainous plateaux of 1,000 to 3,000 feet supported a number of coffee-producing properties. Similar altitudes in St James and Trelawny supported Venture, Lapland, Kenmure, Vaughansfield, Springfield, Catadupa and Mocho plantations, which all produced...