- 992 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

47: The True Story of the Vendetta of the 47 Ronin from Akô

About this book

This is the story of a few men who valued justice more than life. They were members of the large Corps of Samurai in the feudal domain of Akô in western Japan. But when their lord committed the crime of drawing his sword within the castle of the Shogun, the law decreed that he should be sentenced to death, that his heir would not inherit the domain, and all of his vassals would become ronin, dismissed from employment, evicted from their homes, and deprived of their income. All 308 samurai in Akô knew the law and accepted it. And if their lord had succeeded in killing the man he attacked in the castle that would have been the tragic end of this episode. But their lord was subdued and failed to kill his enemy; which meant that yet another law came into play: the Principle of Equal Punishment.

47: The True Story of the Vendetta of the 47 Ronin from Akô tells the harrowing tale of how all this was argued, what was decided, what the results were, and what ultimately became of those 47 men who remained.

47 Ronin tells the tale in immense detail—with maps, graphics and gorgeous illustrations. It provides a richer and more in-depth picture of the Samurai than readers will find in any other medium, offering a comprehensive picture of a tale of justice, honor, politics, and the law of equal punishment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 47: The True Story of the Vendetta of the 47 Ronin from Akô by Thomas Harper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Year of the Serpent

Genroku 14 (1701)

CHAPTER

1

This New Year appears not to augur well.

Edo, New Year’s Season, Genroku 14 (1701)

As always, there were those who said that catastrophe was certain to strike this year, but for once the doomsayers seem to have had some evidence for their dire predictions. On the eve of the New Year, the citizens of Edo, as was their custom, had remained awake throughout the night. Then, in the hour before dawn, dressed in their holiday best, they thronged to the heights and to the seashore, to Takanawa and Shiba, to Atago and Kanda, and especially to the strand in Fukagawa, hoping to greet the first rays of the rising sun and to pray that the Great Peace, which the whole land now enjoyed, would continue. Instead, they found the sky heavily overcast, and no sooner had the clouds begun to lighten than they were suddenly turned black by a near-total eclipse of the sun—80 percent to be precise—plunging the city back into almost total darkness. Astronomers at the Official Observatory were well aware that this eclipse would occur; for them, it was a predictable astronomical event. Yet predictable or no, to the multitude, it remained an omen, and the Shogun’s Junior Council of Elders had already ordered rites to counteract its effects at several of the larger temples. Science notwithstanding, they knew from experience that the appearance of concern was important.

But the magic didn’t work. No sooner had light returned to the city than news began to spread of a ghastly discovery in the house of a respected military family, the Ōkōchi by name, who lived near the new Eitai Bridge. In the vestibule to their home, whither they had gone to open their doors to the first visitors of the New Year, they found the severed head of a woman lying in a pool of blood. Who the woman was and how her head had got there were never subsequently explained. The Ōkōchi did their best to put a propitious interpretation on the event. For a military house, they said, nothing could bring greater good fortune than to take a head on the 1st Day of the New Year. They even built a little shrine to honor their happy find. But they knew as well as anyone that finding the head of a strange woman in their vestibule was not the same as decapitating an enemy on the battlefield.

No, the fourteenth year of Genroku did not get off to a good start. But what future misfortunes might these omens portend? That was still anyone’s guess. The New Year’s season being as hectic as it is, most people just forgot them.

But not everyone. An old man living in retirement on the fringes of the city received the following New Year’s greeting from his younger kinsman, the Chief Elder of the domain of Akō in the western province of Harima:

As this New Year appears not to augur well, I trust you will take particular care to keep in good health. Please rest assured that all of us here, as we grow another year older, remain well. We send you our most cordial good wishes for the New Year’s season.

FIRST MONTH, 1ST DAY

Ōishi Kuranosuke [monogram]

To: Ōishi Mujin Sama and family

The hectic pace of the New Year’s season—sometimes I think that that alone could be the cause of catastrophe. Even a beggar becomes a busy man with the coming of the New Year, at least as long as people continue to throng the temples and shrines. Before long, however, the crowds dwindle, along with their spirit of generosity, and his life returns to normal. A respectable townsman, however, can count on spending the better part of a month discharging his duties and fulfilling his obligations. For a samurai, it can take longer, depending upon his rank—added to which, he has far more demanding standards of decorum. But imagine what it must be like for the Shogun and those involved in the discharge of his obligations. I despair of giving you anything like a precise account of the fifth Shogun’s movements on that morning of the 1st Day of 1701. The documentation is so cryptic, so fragmentary, and so much changes from year to year. But since everything that transpired thereafter traces back to this day, I feel I must at least try.

At dawn on New Year’s Day, the Shogun begins a grueling stint of three full days in which he must receive and reciprocate the greetings of all his clansmen, his vassals, his allied lords, and his liegemen—not to mention the numberless groups of eminent merchants and craftsmen who are not of samurai rank, but whose services he depends upon.

Long before first light, the upper mansions of the great and powerful are alive with preparations for their lords’ progress to the castle. In the lamp-lit inner rooms, the lord himself is being dressed in his most formal court attire. In the long barrack blocks that enclose the property, his vanguard, his Corps of Pages, and his Horse Guards are arming and outfitting themselves. In the storage rooms, lackeys and menials are assembling the equipment of their assigned tasks—the halberds and the lances that identify the house, the umbrellas, the seating mats for the long wait at the dismounting ground, the crested trunks. In the stables, horses are being curried, caparisoned, and saddled. And in the kitchens, tea and rations for the whole procession are being prepared and packed.

Finally, as the night sky turns gray and then crimson, the lord’s palanquin, borne by four men in livery and followed by four more in reserve, is carried to the formal entry hall of the mansion, while in the white-graveled court before it, the procession forms up. When the signal to march is given, His Lordship emerges from his quarters and boards his conveyance; the trunk bearers, in perfect unison, grasp the poles of their burdens, flip them smartly into the air, and settle them upon their shoulders; the gates swing open; the guide of the column takes his place at its head, strides out of the gate, and turns smartly in the direction of the castle.

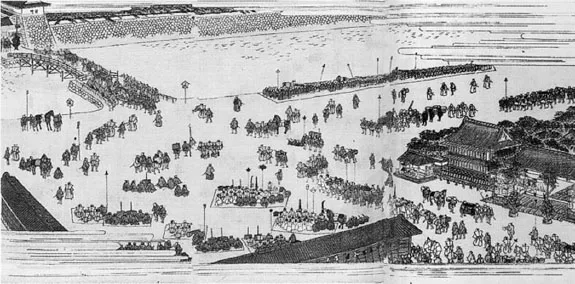

It is a stirring sight to watch these columns converge upon the main gate of the Shogun’s castle, just as the sun is about to rise above the city for the first time in the New Year. They have been ordered to arrive at dawn, and precisely at dawn they arrive—their movements synchronized by the beat of the time drum in its tower on the ramparts of the castle. There are not as many great lords today as on a day of general audience, but those whose appointed day it is are the grandest of grand. One moment, the square is empty, an immaculately swept open ground presided over by the exquisitely fashioned sprays of pine and bamboo that flank the gates of the mansions facing it. The next moment, the streets begin to fill with the precise and purposeful steps of the long trains of the premier military houses of the land. To a man, they are clad in their New Year’s best and groomed to perfection; yet even in their finery, they look as ready for action as for ceremony. Their formal trousers are bloused up above their knees, revealing the muscled calves of men who can—and regularly do—march the length of the land. Their lances look as tall as the masts of ships; the hilts of their swords protrude menacingly; their stance is wide, and their pace firm; their fingers are curled in a loose fist, their elbows tensed, their arms swinging smartly in time with their pace; their gaze is straight and steady, and their faces stern, as though to say, “Touch me, and I’ll kill you; come near me, and I’ll knock you flat.”

Here, in its full glory, is the might that a Shogun can command. The spotter, who runs to the guardhouse and cries out the name of lord and domain as each column approaches, is trained to identify every noble house in the land by the shape of the plumes and scabbards atop its lances. His cries, in turn, send other foot soldiers running to direct the course of the converging columns. Amid all this running about and shouting of commands, these great bodies of warriors move in almost total silence to their appointed places on the dismounting ground. They form up into units, arrange their equipment in neat rows, spread their mats, and take their seats. For all but a few, this is the terminus of their march. Here, for the next four hours or more, they will wait while their lord fulfills his duties in the castle. Inevitably, the mood shifts as the concentration of the march gives way to the resignation of waiting. As ever among warriors too long at their ease, quarrels and fights break out between the lower ranks of the several houses. But these are remarkably few. The better sort of samurai more likely takes a book from the folds of his kimono—perhaps a volume of old poems or, more often, a critique of new offerings at the theaters or even a guide to the ladies of the pleasure quarters. The lackeys sit down on the trunks they have borne here and gossip and smoke. And before long, peddlers of saké and snacks and sweets come weaving through the crowd, doing their best to eke out a living by easing the boredom of their captive market. At the fringes of the ground, small clusters of sightseers appear. Some can be seen turning the pages of the latest Military Register, trying to identify the several lords from the crests on their trunks or the plumes atop their lances. Others—perhaps beggars or country folk—just stand with their mouths agape at the splendor of it all.

Yet while most settle down to a long wait, a few must prepare for the next stage of their lord’s progress. Six of his closest attendants gather around his palanquin—two on either side and two before it—while at the rear, there follow two trunk bearers, the sandal bearer, and the umbrella bearer. When all is in order, His Lordship’s palanquin is again hoisted to the shoulders of its bearers, and they cross the moat to the main gate. It is a deceptively modest gate, designed not to withstand attack, but to draw an enemy into the heavily fortified trap of stone walls that lie behind its doors. Once within this bastion, the small suite quickly vanishes from the sight of the force left behind on the dismounting ground. It turns to the right; passes through a massive inner gate; emerges into the Third Perimeter, the outermost of the moated enclosures; turns sharply to the left; and traverses another broad yard to the Alighting Bridge. Here, again, the procession must halt, in front of the long guardhouse of the Company of One Hundred, and it may go no farther. An attendant crouches and slides open the door to the palanquin. Then the sandal bearer, from a position to the rear of the conveyance where he will not violate His Lordship’s line of vision, takes aim and with the easy skill of long practice tosses his lord’s sandals—first the right, then the left—so that they land in perfect alignment and in the precise position where His Lordship will step as he emerges. For even a lord whose domain covers an entire province and more must cross this bridge on foot.

figure 1

The dismounting ground at the main gate of Edo Castle. (Tokugawa seiseiroku, 1889)

From here on, His Lordship is attended by only his Commander of the Bodyguard, his Liaison Officer, his sandal bearer, and one of the trunk bearers—and if it is raining, his umbrella bearer as well. They cross the Alighting Bridge, at the far end of which they pass through the Third Gate into another fortified enceinte. Here they exit to the left, into the yard of the Second Perimeter; pass yet another guardhouse; and then veer to the right toward the Middle Gate, the only one of the six inner gates that does not open into a stone-walled trap. At this gate, the trunk bearer must halt and wait.

Once through the Middle Gate, the lord and his attendants ascend the long winding causeway rising to the Central Perimeter. Finally, they enter the last of the fortified enclosures, and when they emerge from the Great Shoin Gate on the far side of it, they are within sight of the entryway to the palace. Here the lord must leave behind even the last remnants of his entourage. A samurai of good lineage, sent ahead for the purpose, takes his long sword, and when His Lordship steps up into the entry hall, the sandal bearer retrieves his sandals. But only one member of his entourage, usually his Liaison Officer, is allowed actually to enter the palace. And even this man may not accompany his lord; he must wait in the Fern-Palm Room until the ceremonies are over, at which time it is his duty to receive and carry away the gifts that his lord has been given by the Shogun. In the meantime, the Commander of the Bodyguard, the Keeper of the Sword, and the lackeys withdraw. His Lordship enters the palace, armed with only his short sword and attended by only a Palace Usher with shaven head, one of that great host of hundreds known familiarly, at least to their superiors, as the Tea Monks.

And so, one after another, the great lords arrive, traveling in pomp and splendor as far as the castle gates, and then gradually shedding the protection of their entourage as they penetrate deeper into the maze of walls and moats and finally are ushered, alone and disarmed, to their appointed places in the palace, there to await their turn to greet the Shogun.

In the meantime, the Shogun himself has been quite as busy as any of the lords now arriving. Well before the sun rises over the ramparts, his preparations are nearly complete. His body bathed, his teeth cleaned, his hair dressed, and his regalia laid out in readiness, it remains only for his personal attendants to help him dress.

His first destination is the Women’s Palace, where he exchanges greetings with his wife. This visit requires only a middling level of formal costume—a standard blue kimono with crosshatched midriff, a heavily starched linen vest with sharply pointed shoulders, and linen tr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note to the Reader

- Prologue: Tokyo, 1915

- Part I. Year of the Serpent: Genroku 14 (1701)

- Part II. Year of the Horse: Genroku 15 (1702)

- Part III. Year of the Ram: Genroku 16 (1703)

- Part IV. The After Years

- Epilogue: Tokyo, 1916

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography