Introduction

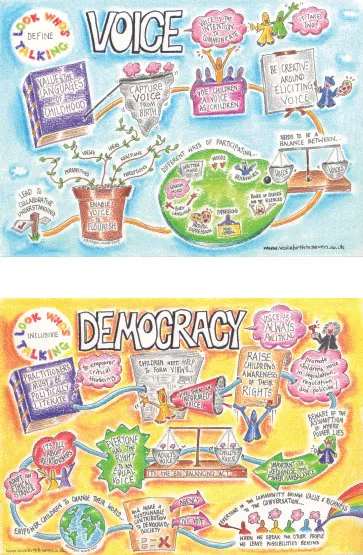

The aim of this book is to support practitioners in eliciting young children’s voice. This will require, for some, a shift in individual and collective practices. In order to understand fully what voice and democracy mean in the context of practices at a local level, it is important to be cognisant of the global context, which is what we aim briefly to outine here before turning our attention to unpacking notions of children’s voice and democracy.

We start by highlighting global initiatives which have focused on enhancing and promoting children’s rights. Having an understanding about the intentions of these initiatives is significant in the context of this chapter as practices pertaining to children’s voice and democracy are rooted in how we understand children as rights holders. While there have been various human rights declarations outlining the rights to which all humans are entitled, the first global convention that outlined specific rights for the protection, freedom and participation of children was the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). It is the world’s most widely ratified treaty relating to human rights, highlighting a series of political, social, civil, economic and cultural rights that all children should enjoy, regardless of their religion, gender, language, ethnicity or abilities. There are strong interconnections between the individual articles that make up the UNCRC.

Since 1989, all countries worldwide, with the exception of the United States of America, have ratified the UNCRC. Thus, the UNCRC has prompted action on a global scale, and is the basis upon which much domestic and international legislation has subsequently been based. In 1994, the United Nations (UN) initiated the Decade for Human Rights Education (1995–2004), calling for countries ‘to include human rights, humanitarian law, democracy and rule of law as subjects in the curricula of all learning institutions in formal and non-formal settings’. Following this, in 2005, the UN launched the World Programme for Human Rights Education ‘to advance the implementation of human rights education programmes in all sectors’ (UN, 2005). The World Programme was divided into four consecutive phases, each focusing on different issues. For example, the first phase (2005 to 2009) centred around integrating human rights education into primary and secondary schools (UN, 2006) and the fourth and current phase (2020 to 2024) focuses on youth, ‘with a special emphasis on education and training in equality, human rights and non-discrimination, and inclusion and respect for diversity with the aim of building inclusive and peaceful societies’ (UN, 2018). This fourth phase is purposefully aligned with the UN’s recently published 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which address global challenges relating to ‘poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity, and peach and justice’ (UN, 2016). The SDGs have been developed with all global citizens in mind and are described by the UN as ‘the blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all’ (ibid.).

These three UN initiatives – the UNCRC, the World Programme for Human Rights Education and the Sustainable Development Goals – provide the context in which this chapter is based. Respecting and promoting rights and sustainability are at the heart of what we seek to achieve with and for children, and this necessitates adopting an approach that places notions of children’s voice and democracy at the core of this endeavor.

Political children

Often the UNCRC is discussed in terms of the three areas on which the rights within it focus: protection, provision and participation. The elements of protection and provision pertain to the duties of adults, while participation shifts the locus of action to children (Cassidy, 2012; Archard, 2015). Children’s participation is fundamental to notions of voice and democracy. Their right to participation is clearly articulated within Article 12 of the UNCRC, which gives children ‘the right to express their views freely in all matters affecting [them]’ (UNCRC, 1989, 5). This is both thought-provoking and problematic, since there are very few issues that do not concern children (Cassidy, 2017). Children are, as Biesta et al. (2009) note, ‘involved in the fabric of life and society’ (p. 9). As such, it is important that children are inducted into practices that will enable their participation, now and in the future. Participation is wide in scope and political in nature and, in arguing that children should be inducted into society in order that they may participate now and in the future, we also acknowledge that participation, by its very nature, is political. Thus, by recognising that children have rights, we accept them as political beings.

Rights and democracy are complex, overlapping concepts (Landman, 2018). Supporting children to understand themselves as rights holders is central to developing democratic approaches, and democratic approaches are central to upholding children’s rights, particularly in relation to participation. This suggests that practitioners – those working with young children – are required to be politically literate and that they recognise the ways in which they might promote democratic approaches to children’s participation and engagement. During the second phase of the World Programme for Human Rights Education (2010–2014) (UN, 2009), which emphasised the need for human rights training for teachers and other educators, the Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training (UN, 2011) was published, highlighting the need for children’s human rights education. The Declaration proposed that children should learn about, through and for human rights. Expanding on the meaning attributed to this proposal, Robinson et al. (2018) advocate that, in relation to children’s human rights education, practitioners have a responsibility to:

- teach children about the nature and content of human rights declarations and conventions and to raise children’s understanding of the values inherent within these;

- create an environment in which practitioners acknowledge and respect human rights through enacting human rights values; and

- educate children for human rights through promoting children’s agency and supporting children to actively uphold and protect their own rights and the rights of others.

The essence of children learning about, through and for human rights requires an environment in which children are supported to be participative, by adopting consultative and dialogic practices. This approach suggests a particular understanding of democracy and, as Biesta (2008) asserts, it is important to be clear about what form of democracy we wish to promote. This, consequently, requires that we must clarify what our understanding of democracy might imply in relation to children and their participation, notably with respect to voice. Viewing children as political beings – as participants – requires us to recognise and accept their capacity for agency.

Capacity

Our perceptions about children’s capacities, or lack thereof, are determined by how we view the social construction of childhood (Prout, 2011). For example, developmental psychology presents children as deficient in some way and as ‘becoming adults’ (McDonald, 2009) whereby children progress through stages in understanding and thinking that, more or less, progress at a rate that can be mapped against their age. An opposing viewpoint, and the stance taken in this chapter, is that children are competent, capable beings. Certainly, children will have had fewer experiences of participation than their older counterparts, so they will be less practised, but we cannot assume from this that they do not have the capacity to think or reason for themselves, particularly on matters that affect them. These opposing views of childhood present challenges in relation to how Article 12 of the UNCRC is interpreted. As identified earlier, Article 12 gives children the right to express their views on matters affecting them. However, the article also asserts that children’s views will be ‘given due weight according to the age and mat...