- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Methods & Theories of Art History Third Edition

About this book

This book is an accessible introduction to the critical theories used in analysing art. It covers a broad range of approaches, presenting individual arguments, controversies and divergent perspectives. This edition has been updated to reflect recent scholarship in contemporary art and has been broken down into smaller sections for greater accessibility. The book begins with a revised discussion of the difference between method and theory. The following chapters apply the varying approaches to works of art, some of them new to this edition. The book ends with a new conclusion that focuses on the way the study of art is informed by theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Methods & Theories of Art History Third Edition by Anne D'Alleva,Michael Cothren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Style, iconography, and iconology

This first chapter surveys some of the most basic and widely used methods of art-historical interpretation: stylistic analysis, iconographic identification, and iconological interpretation. Since they are usually introduced in beginning-level classes on art history, we sometimes think of these methods and strategies as “natural” or “obvious,” standing somehow outside the theoretical frameworks that support more “serious” art-historical study. But theories as well as methods are at play here. In this chapter, we will not only outline and demonstrate the methods but comment on their assumptions and theoretical underpinnings. It would be irresponsible to continue to use these investigative tools without understanding their own origins and meanings.

Style

Style is a favorite word in art history. There are styles of individual works, the developing personal styles of individual artists, styles associated with particular times and places, moods and subjects, schools and movements, training and influence. Style is not an easy word to define, but in a now-classic article of 1953—published in an anthology on anthropology—influential art historian Meyer Schapiro (1904–96) may have given the art-historical usage of the word its clearest definition: “By style is meant the constant form—and sometimes the constant elements, qualities, and expression—in the art of an individual or a group.” He goes on, “To the historian of art, style is an essential object of investigation. He [sic] studies its inner correspondences, its life-history, and the problems of its formation and change… style is, above all, a system of forms with a quality and a meaningful expression through which the personality of the artist and the broad outlook of a group are visible.” (p.287)

Practicing stylistic analysis

For many art historians, analyzing the formal qualities and visual structure of a work of art is an indispensable first step in coming to an understanding of its character and significance, whatever the theoretical perspective taken by the interpreter. This practice is based on the belief, on the one hand, that the unique expressive character of a work of art can be determined and characterized by formal analysis, and, on the other hand, that fundamental relationships between one work and other works are revealed by recognizing their shared formal features or style. Stylistic analysis is performed first by assessing the expressive character and importance of the work’s individual formal features— such as line, color, light, form, and space—and then by turning to its composition, the overall arrangement and organizational structure of the representation as a whole.

For example, a late nineteenth-century landscape painting by Claude Monet in the National Gallery in Washington (Figure 1.1) is easily characterized on first glance by a set of salient formal signposts. A series of stacked horizontal bands of color run across the canvas, defined by loose brush strokes and distinguished by uniformities of hue (mostly blues and greens). The bands alternate regularly—light, dark, light, dark, light, from bottom to top. The more detailed forms created by the quick touches of pigment across the lowest and tallest band suggest that it is in the foreground, whereas the smaller size of the dark trees further up on the surface, as well as the more diffuse appearance of the clouds forming the uppermost strip, push the top of the painting into the background. Since it reflects the trees in the distance, the body of water at the middle of the canvas represents the middle ground of the spatial organization. Implied overlapping of the bands is consistent with these observations and gives a sense of receding space within the softy illuminated world of the painting as a whole. On the other hand, the repetition of shapes, the homogeneity of color, and the mirrored forms traversing the lake underline a sense of surface pattern that, more than anything, pulls the motifs of the painting together into an organized whole.

1.1 Claude Monet, Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil, 1880. Oil on canvas. 287/8 x 399/16 in (73.4 x 100.5cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.177).

In 1879, Monet and his family moved from Argenteuil to the village of Vétheuil, on the banks of the River Seine, about 35 miles northwest of Paris, and, soon after they arrived, his wife Camille died from uterine cancer at the age of 32, leaving him as the single parent of two young sons. In the following few years, he began to paint the surrounding landscapes, producing some of the greatest works of his long career as an artist, while his friends helped him care for his children.

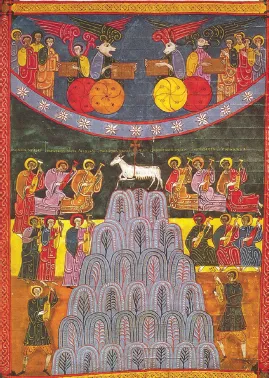

Like Monet’s painting, a smaller and much older picture (Figure 1.2)—painted by Fecundus to be encountered intimately, within a book, rather than hung in open access on a wall—is also organized, in part, by the distribution of color. Bands of strongly divergent hues create stacked fields of color, separated from each other by sharp lines and working together to create a background screen running behind the equally sharply delineated forms silhouetted against them. In this case, however, other formal factors are more significant in creating visual structure. The bands do not present or create the subject; they extend behind the subject, which floats as a composition of evenly distributed flattened forms in front of them, each outlined and alternating in color. Those forms, rather than the horizontal spread of color, grab the viewers’ attention. Fecundus has arranged them within the painting in a strictly symmetrical system, with human and fanciful creatures pushed to the sides and a large triangular mound, with a lamb sitting on the top, dominating the central space on the vertical axis. In fact, this painting contains two separate pictures: the lower two-thirds is a squarish, rectilinear composition of shapes that fill most of the available space and conform to the straight sides and bottom of the frame. Above this composition is another arrangement of figures conceived in relation to a curving internal frame that separates this world from the one below. Though there are correspondences of forms and colors across the barrier between these worlds, the artist has worked to separate them, not only by the internal frame but by the differing compositions that fill these two areas.

1.2 Fecundus, “Adoration of the Lamb,” painted in 1047 for Ferdinand I of Castile and León and Queen Sasha, fol. 205r in an illustrated manuscript of the Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse (known as the León Apocalypse). 14¼ x 10½in (36.1 x 26.7cm). Now in Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, MS BVit. 14.2.

Neither of these rudimentary and incomplete formal analyses of two very different paintings brings us to a full understanding of them. The observations offered here are meant as beginnings. Much more formal analysis is required before justice can be done to the complex visual structures of these two examples, but the primary language of these paintings is visual and spatial rather than verbal and linear. Most of us will want to employ other methods to probe the rich contexts beyond the formal structures of these paintings—a rich set of social and scientific factors that will associate Impressionism with Monet’s picture and the Mozarabic world in which Fecundus lived and worked (Schapiro, 1939). But before addressing those questions by exploring secondary literature, we may first need to get to know these pictures on their own visual terms. They are the primary sources.

Connoisseurship

Connoisseurship is a specialized type of formal analysis that aims to associate works of art with a particular artist, artistic movement, or moment in time. The visual skills and expertise required to do this work must be developed over years of looking at the art of a particular time and place or the output of a single artist. Connoisseurship is also a tool used to judge the authenticity of a work of art, to separate genuine works from forgeries, and works of an artist from those made by their followers, copyists, or forgers. This latter aspect of connoisseurship sometimes associates it with the art market since such judgments have financial implications. But, for art-historical scholarship, it can be a useful tool in a quest for the identification, authentication, and attribution of the primary objects of investigation.

The current practice of connoisseurship is rooted in the ideas and work of Giovanni Morelli (1816–91), an Italian intellectual and political figure, who had studied medicine and comparative anatomy in Germany. Because of his longstanding interest in art, and his scientific training, Morelli developed a concern that attributions of Italian “Old Master” paintings in European museums were based on intuition rather than empirical evidence. He developed an evaluation process rooted in scientific taxonomic and diagnostic methods. During the 1870s and 1880s, in a series of articles published under the pseudonym Ivan Lermolieff, he challenged attributions of paintings in major museums in Rome, Munich, Dresden, and Berlin. In the 1890s, he published a summary and extension of this work in a two-volume study that appeared in Italian, German, and English editions and had a huge impact across Europe and into the United States.

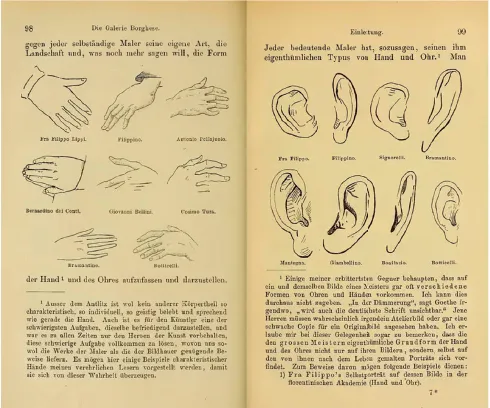

Morelli not only proposed that verifiable empirical evidence should be the basis for determinations of authorship and authenticity, he also claimed that the best evidence for such conclusions resided in the seemingly trivial or marginal aspects of paintings. For instance, an assessment of a painting’s overall composition or the facial expressions of its figures were less revealing as aspects of individual authorship since they were usually indications of the broad period style of the artist’s time and place. More revealing was the way artists painted less obvious or marginal aspects of figures—such as their hands or ears. Here, he proposed, artists adhere to personal conventions almost automatically, rather than consciously conforming to current fashion or observation. To illustrate his point, Morelli included in his book line drawings of typical ears and hands in the securely authenticated works of individual painters (Figure 1.3).

1.3 Line drawings of typical hands and ears in the works of individual Italian Renaissance painters. From Giovanni Morelli, Italian Painters: Critical Studies of their Works, 2 vols., London, 1892–3.

Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg argued that Morelli’s emphasis on finding “truth” in seemingly insignificant evidence is not limited to him nor to the study of art during the late nineteenth century. In the Sherlock Holmes stories and novels of Arthur Conan Doyle (published between 1887 and 1927), the protagonist’s forensic gifts come from his ability to draw significance from seemingly insignificant evidence that those around him do not even notice. In a 1914 article on Michelangelo’s Moses, Sigmund Freud credited his reading of Morelli’s synthetic two-volume work on Italian painters (the Italian edition was in Freud’s library) as influential in his development of psychoanalytic theory. For Ginzburg, overlooked details in the work of Morelli, Conan Doyle, and Freud provide the key to uncovering a deeper and more significant reality, a notion all three absorbed in their medical training where superficial symptoms provide the means for diagnosing underlying disease.

Influential American art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959) encountered the work of Morelli while studying in England and became an active disciple of Morelli’s empirically based connoisseurship. In 1902, he published a systematic account of Morelli’s notion of the connoisseur in an essay entitled “The Rudiments of Connoisseurship,” and he demonstrated the process in his numerous publications on Italian Renaissance art. Because of Berenson’s secret collaboration with prominent international art dealer Joseph Duveen—receiving lavish compensation for using his reputation as a connoisseur to elevate the prices of paintings sold to American millionaire collectors—his reputation as an art historian has been tarnished, and the whole enterprise of connoisseurship within academic art history fell under suspicion.

Many art historians still dismiss connoisseurship as a superficial formalist study, emphasizing taste and judgment rather than contextual interpretation or social significance. For others, connoisseurship’s focus on individuality feeds into a problematic emphasis on seeing the history of art as a sequence of great geniuses rather than part of a broader cultural activity. On the other hand, art historians who study periods where the identities, or at least the names, of individual artists are not known, have seen connoisseurship as a means of bringing a human dimension to art that is often referred to dismissively as anonymous (see Sir John Beazley’s studies on the painters of ancient Greek ceramic vessels and Michael Cothren’s work on twelfth- and thirteenth-century glass painters).

Making judgments about authenticity and authorship can be an important first step in many art-historical studies whose goal is to probe the cultural contexts of works of art from any number of theoretical perspectives. But, today, the close visual anal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: How to use this book

- Introduction: Thinking about method and theory

- Chapter 1: Style, iconography, and iconology

- Chapter 2: Semiotics

- Chapter 3: Marxist perspectives

- Chapter 4: Feminisms, sexualities, and queer theory

- Chapter 5: Cultural studies and post-colonial theory

- Chapter 6: Psychoanalysis and reception theory

- Chapter 7: Rethinking knowledge and interpretation in postmodern art history

- Conclusion: Knowing what to do and assessing its value

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Photo credits