![]()

PART ONE

MAKING POLICY IN SAUDI ARABIA

![]()

1 IS EVIDENCE USED FOR POLICYMAKING IN SAUDI ARABIA?

Lessons from an international research-policy partnership in labour policy

Ammar A. Malik

Introduction

The public policy process – from agenda setting to problem identification and from solution design to implementation – is strengthened by rigorously collected, on-the-ground evidence for producing timely analytics. The quality of each country’s research-to-policy ecosystem, from scholarly outputs by university to policy debates by think tanks, determines how the extent to which government decision-making improves public welfare (Struyk 2007). It enables policymakers to access relevant scientific evidence and its impact on society in actionable ways. Besides universities and think tanks, private foundations, not-for-profit agencies, foreign donors and for-profit businesses all play critical roles in shaping this ecosystem, which is marked by the interaction of government and non-government entities.

But in countries lacking robust home-grown research institutions, external actors could end up playing key roles in shaping the policy agenda and influencing the policy development process. In low- and middle-income countries, international development partners (aka ‘donors’) provide governments much needed technical assistance and capacity-building services mainly through international and some local private contractors. In many high-income countries such as Saudi Arabia, but also across the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) where governments offer lucrative contracts and generous terms, major management consulting firms have increased foothold in public sector consulting. They typically customize and apply internationally tested, private sector–inspired solution models in response to policy challenges, coupled with very effective communication tools such as interactive data dashboards (Haque 2017).

In this environment, what role can international universities and public policy academics play in improving public policymaking? Should they provide infrastructure and capacity-building support by establishing applied research centres? To what extent is there space for them to work directly with decision-makers? Or, should they focus on their narrow research goals, and restrict support to policy insights in academic publications? What incentives do governments have to engage with slow-moving academic projects, rather than rapid-response consulting service providers? In this chapter, I present insights from a major, multi-year research-policy collaboration between Harvard University economists and Saudi ministries of labour and social development, and education. This framing is thus set within these substantive areas, but lessons drawn from the engagement could apply to all sectors of public policy.

Since 2014, Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD), a research programme at the Harvard Kennedy School, has undertaken a series of research projects in collaboration with the ministries of labour, social development and education. The engagement focused on optimizing the Saudi labour market by tapping into national human capital reserves and promoting citizen welfare, particularly that of women and youth. Harvard economists jointly identified priorities with policymakers, and help design, evaluate and re-design labour market policies. EPoD also offered customized capacity-building programmes, many focused on incorporating data-informed insights into policymaking, to support the mission of improving evidence-informed policymaking.

This experience has produced not only academic articles, policy briefs and insights for decision-makers’ consideration, it has also accorded opportunities to reflect on the domestic policymaking process in Saudi Arabia, particularly the use of evidence in decision-making. The objective of this chapter is to highlight those lessons, situating them within the conceptual framework of evidence-based policy and making recommendations for improving the status quo.

Because no single government agency in Saudi Arabia is fully responsible for improving the research-policy ecosystem, a nationwide approach is required to improve avenues for rigorous evidence to be utilized for crucial public decisions. In the absence of such an effort, the somewhat inefficient and risk-laden public policymaking environment will continue remaining a drain on public resources. This chapter, therefore, offers recommendations for Saudi policymakers to improve their country’s approach towards public decisions that would improve social welfare while creating institutionalized capacity for doing so into the future.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. After this introduction, Harvard’s Smart Policy Design and Implementation (SPDI) methodology and its application potential is introduced as a powerful tool for researchers and policymakers to engage in substantive and mutually beneficial conversations around the most pressing public policy challenges. The EPoD–Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF) engagement is then introduced, before delving into the broad strokes of Saudi Arabia’s labour and economic policy challenge and ways in which the Vision 2030 targets have set the country on the path of reforming existing systems. Key lessons from the engagement are then discussed, before introducing a series of conclusions and recommendations for senior government officials to contemplate and potentially implement.

Smart policy design and implementation

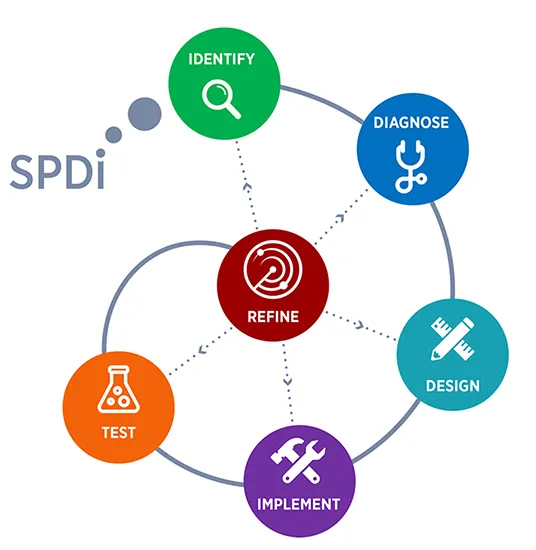

The aforementioned engagement was based on Harvard’s SPDI framework, a unique problem-driven and iterative approach for identifying and diagnosing policy problems, designing, testing and refining solution that creates evidence-based policies for greater social welfare. In the Saudi context, this is a unique engagement style which is directly opposed to solution-driven approaches of outside experts, particularly management consultants. By default, their diagnostics and solution expertise are based on international best practices and benchmarking based on their extensive experience of dealing with similar problems in comparable countries around the world.

In practice, as illustrated in Figure 1.1, SPDI is based on the belief that continuous self-learning and improvement is the only way to have positive impact on society. It must become the basis of researcher-policymaker engagements, which would in turn bring value to both sides, i.e. robust academic contributions on the one hand, and highly impactful policy solutions on the other.

FIGURE 1.1 SPDI in action (Source: epod.cid.harvard.edu.)

The six stages of this methodology are all interconnected and are as follows:

1. Identify. Public, private and academic stakeholders combine information on policy priorities with economic insights to identify a priority problem to address.

2. Diagnose. Use insights from economic theory and empirical evidence to diagnose underlying market or policy failures.

3. Design. Together, researchers and policymakers design innovative solutions that are financially, administratively and politically feasible.

4. Implement. Support implementation and monitor to ensure effective delivery.

5. Test. Rigorously test solution at scale to see what is working and what needs attention for further improvement.

6. Refine. Use lessons learned at each stage to refine existing designs and identify the next set of objectives and challenges.

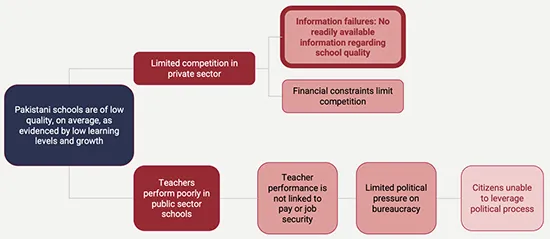

To showcase this approach in action, the recent example of Pakistan’s education system is a useful case. Policymakers in the Punjab province identified the following problem statement: Pakistani schools are of low quality, on average, as evidenced by low learning levels and growth. To scope out this statement, researchers found that in 2016, standardized test scores in rural areas for grade 3 students was such that 72 per cent could not do two-digit subtraction and 85 per cent could not read a sentence in English. Following the SPDI steps, researchers and policymakers collaborated to put together the theory of change given below, focusing not just on apparent symptoms of the problem statement above, but going one step deeper to uncover its origins in deep-rooted issues.

The underlying issue in education sector’s poor performance is not just quality of teaching, lack of facilities or even parents’ own educational attainment, but rather information failures due to which families are not able to optimize their decision regarding children’s school attendance. If it was not for this approach, researchers and policymakers could have misdiagnosed the problem altogether. In Saudi Arabia, the same approach was applied to a series of labour market challenges identified by policymakers and further refined through workshops, forming the basis of several follow-on research projects addressing individual research questions.

FIGURE 1.2 Sample SPDI application – Education in Pakistan.

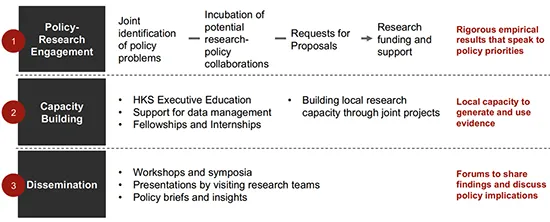

With this approach in mind, Harvard and the Saudi Ministry of Labor and Social Development formed a multi-year partnership that operationalizes the SPDI approach. Researchers were thus embedded within the HRDF, which was charged with designing and implementing labour market programmes based on the Ministry’s policy guidance. Because sound public decision-making requires appropriate matching between demand and supply of policy analytics which is delivered to stakeholders in the correct format, this engagement was based on a three-pronged approach including policy-research engagement producing evidence, capacity-building to foster demand for analytics and policy dissemination to get the right information into the hands of the right decision-makers in the right format.

The intersection of this three-part structure is such that the joint identification of problems with policymakers requires them to understand the value of evidence which in turn depends on availability and analysis of empirical data. This is achieved by having them take courses as part of the executive education, enrolment into which depends on potential recipients appreciating the value of taking them. A series of symposia, workshops and policy briefs enables policy dialogue between researchers and policymakers, based on economic theory and rigorous data analytics.

This major engagement has, for the first time, brought some of the world’s foremost universities and economists to work on Saudi Arabia’s labour policy challenges. They have not only engaged with policymakers but also undertaken data analysis on programmatic information obtained by HRDF and lead fieldwork. This is now seeing Saudi Arabia’s economic policies being debated at prominent economics conferences and analysis appearing in top journals, i.e. Saudi Arabia is now firmly on the map of the world’s premium economic policy forums.

FIGURE 1.3 EPoD–HRDF engagement structure overview.

FIGURE 1.4 EPoD–HRDF collaboration at a glance.

Saudi labour market policy

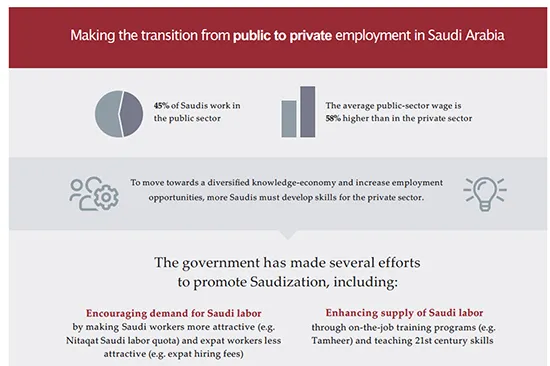

Since 2011, the Saudi government has been making efforts to bolster Saudi citizens’ employment in the private sector in realization of the limits to public sector employment. But the underlying idea of Saudization, i.e. encouraging private companies to replace expatriates with citizens, has featured in policy discussions since the 1980s. For example, the Fifth Development Plan (1995–2000) aimed to create 319,500 Saudi jobs, but in reality during this period the number of expatriate workers increased by over 58,000 (Looney 2004). This failure was simply reflective of the underlying economic reality that hiring expatriate for the same jobs was more economical for private companies, whose quest for profits and efficiency compelled them to de-prioritize citizens in their workforces. Many large private businesses have also lobbied for years to remove such conditions, citing lack of requisite skill sets among citizen workforce and costs of hiring them as main reasons (Leber 2019).

But during the last decade, starting with King Abdullah’s US$98 billion economic package announced in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the Nitaqat programme reversed this trend for the upcoming decade. As an implementing arm of the MLSD, HRDF has been at the forefront of efforts to work with both the demand and supply sides of the labour market to create more private sector jobs for Saudi citizens including trainings and subsidies, focused on individuals and firms respectively. Through its sixth thematic area, the Saudi (NTP) outlined several specific key performance indicators (KPIs) and identified MLSD and HRDF as key agencies responsible for achieving them. Prominent among them is the desire to increase women’s labour force participation, besides improving working conditions for expatriate workers and attracting suitable global talent to work, which goes hand in hand with other objectives related to improving the quality of life in the Kingdom.

Studies within this engagement directly addressed several of the twenty-four programmes designed to achieve these NTP targets. For example, the NTP’s focus on creating an effective National Employment Portal and improving Saudi workers’ soft and technical skills were key motivations for studies on the HRDF-managed Taqat platform. In order to improve women jobseekers’ matching with potential employers and to overcome the information asymmetry preventing them from applying to the right sectors and occupations, tens of thousands logging into the system were offered information (through pop-ups) on which sectors and occupations are in high or low demand in any given month. This enabled women to apply for the most in-demand sectors, significantly increasing their chances of getting call-backs for well-paying jobs.

FIGURE 1.5 Public to private employment.1

But in reality, the current state of the Saudi private enterprise economy is such that they are under tremendous pressure to grow and become more competitive, but the Saudi dependence on oil is hampering progress. The labour market statistics from the Saudi government, released for Q4 2020, indicate that despite the economic impact of Covid-19, unemployment rates fell to 12.6 per cent down from 14.9 per cent in Q3 2020. Female labour force participation improved in recent years, but because women are in generally less qualified and less experienced than men, they are struggling to ge...