![]()

CHAPTER 1

OUR BRAIN’S POST-IT NOTE

• WHAT is working memory?

• WHERE is working memory in the brain?

• WHY is working memory linked to learning?

My (Tracy’s) journey began, on a crisp October day about 10 years ago.

I was surrounded by a sea of small and eager faces, the children all in neatly pressed uniforms. As part of a government-funded project, I was working with kindergarteners to understand what cognitive skills are important for academic success.

I met Andrew that day. That 6-year-old boy stood out from the rest. He loved being at school and made friends quickly. In the classroom, he was always excited about participating and would raise his hand to answer questions. Andrew enjoyed ‘story time’ best, when Mrs Smith would ask the children to present a short story. Andrew loved telling stories and would be so animated and use such creative examples that all the children enjoyed them as well.

As the school year progressed, I noticed that Andrew began to struggle with daily classroom activities. He would often forget simple instructions or get them mixed up. When all the other children were putting their books away and getting ready for the next activity, Andrew would be standing in the middle of room, looking around confused. When Mrs Smith asked him why he was standing there, he just shrugged his shoulders. She tried asking him to write down the instructions so he could remember what to do. But by the time he got back to his desk, he had forgotten what he was supposed to write down.

His biggest problem seemed to be in writing activities. He would often get confused and repeat his letters. Even spelling his name was a struggle, he would write it with two ‘A’s or miss out the ‘W’ at the end. Mrs Smith tried moving him closer to the board so he could follow along better. This didn’t seem to work; he would still get confused.

Mrs Smith was at a loss. She always had to repeat instructions to Andrew but he never seemed to listen. It was as if her words went in one ear and out the other. On another occasion an assistant found him at his desk not working. When she asked him why he wasn’t doing the assignment, he hung his head and said, ‘I’ve forgotten. Sometimes I get mixed up and I am worried that teacher will get angry at me.’

His parents contacted me to see if I could help. They were concerned that Andrew might have a learning disability. When I tested Andrew on a range of psychological tests, I was surprised to find that he had an average IQ. Yet, by the end of the school year, he was at the bottom of the class.

Two years later, I went back to the school to conduct some follow-up testing on the children. Andrew seemed like such a different boy. He was placed in the lowest ability groups for language and math. He became frustrated more easily and would not even attempt some activities, especially if they involved writing. His grades were poor and he often handed in incomplete work. He only seemed happy on the playground.

Although I wasn’t able to follow up on Andrew, I never forgot him. His predicament inspired me to deeply research how we can support thousands of students who, like Andrew, struggle in class through no fault of their own. This book is about a powerful cognitive skill called working memory that, when properly supported, can stop students like Andrew from remembering their school years as a frustrating experience.

A foundational classroom skill

It is hard to conceive of a classroom activity that does not involve working memory – our ability to work with information. In fact, it would be impossible for students to learn without working memory. From following instructions to reading a sentence, from sounding out an unfamiliar word to calculating a math problem, nearly everything a student does in the classroom requires working with information. Even when a student is asked to do something simple, like take out their science book and open it to page 289, they have to use their working memory. They have to work with a number of pieces of information, including looking for the book in the right place, such as recalling that it is in their desk and not in their backpack, identifying which book is in fact their science book, and finally guesstimating where among the thick stack of pages they are most likely to find the correct one. If they overestimate or underestimate, they have to use their working memory to adjust, and flip forwards or backwards until they finally find page 289.

Most children have a working memory that is strong enough to quickly find the book and open to the correct page, but some don’t – approximately 10% in any classroom. A student who loses focus and often daydreams may fall in this 10%. A student who isn’t living up to their potential may fall in this 10%. A student who may seem unmotivated may fall in this 10%. In the past, many of these students would have languished at the bottom of the class, because their problems seemed insurmountable and a standard remedy like extra tuition didn’t solve them. But emerging evidence shows that many of these children can improve their performance by focusing on their working memory. Working memory is a foundational skill in the classroom and when properly supported it can often turn around a struggling student’s prospects.

WHAT: What is working memory?

One way to think of working memory is as the brain’s ‘Post-it note’. We make mental scribbles of what we need to remember. In addition to remembering information, we also use working memory to process or manage that information, even in the face of distraction. In a busy classroom, with classmates talking, pencils dropping, and papers rustling, the student has to use their working memory to ignore the activity around them and focus on what they need to accomplish.

Working memory is critical for a variety of activities at school, from reading comprehension and math to copying from the board and navigating around school. In the classroom, we use verbal working memory to remember instructions, learn language, and complete reading comprehension tasks. Visual–spatial working memory is linked to math skills and remembering sequences of patterns, images, and locations. Below are specific examples of activities requiring working memory taken from real classrooms.

Classroom activities that involve verbal working memory

• Remembering and carrying out lengthy instructions. Here is an example from a classroom of 6-year-olds: Put your sheets on the green table, put the arrow cards in the packet, put your pencil away, and come and sit on the carpet. Students with poor working memory are usually the first ones to sit down on the carpet – because they carried out only the first part of the instruction but forgot the rest!

• Remembering and writing down text, including words, sentences, and paragraphs.

• Remembering word lists that sound similar (example: mat, man, map, mad).

• Remembering sentences with complicated grammatical structure, such as To save the princess, the knight fought the dragon, which is harder to understand than The knight fought the dragon to save the princess.

Classroom activities that involve visual–spatial working memory

• Solving a mental math problem.

• Keeping track of their place when writing a sentence from the board. The student with poor working memory will often repeat or skip letters.

• Using pictures or images to retell a story. The student with poor working memory may get confused about the order of events in the story or even leave out key events.

• Identifying missing numbers in a sequence: 0, 1, 2, __, 4, 5, __.

Working memory versus short-term memory

Working memory is distinct from short-term memory, which lets you remember information for a brief time, usually a few seconds. Students use short-term memory when they look at something on the board, like 42 + 18, and remember it long enough to write it down. But they use their working memory to solve the problem, for example, by adding 40 to 10, holding 50 in mind, next adding 2 to 8, and adding both answers to get 60. Think of working memory as ‘work’-ing with information to remember.

Working memory versus long-term memory

Working memory is also distinct from long-term memory. For a student, long-term memory includes the library of knowledge they have accumulated in the course of their academic career. This may be math facts (6 × 4 = 24), spelling rules (‘i’ before ‘e’ except after ‘c’), scientific and historical knowledge, or the different sounds that phonemes make. Working memory is like a librarian who pulls the appropriate knowledge out of their library when it is needed. For example, if you ask a student to name the first president of the United States, it is their working memory that searches through their long-term memory and finds ‘George Washington’.

Try It: Verbal working memory Read these sentences and decide if they are true or false:

1. Bananas live in water: true or false?

2. Flowers smell nice: true or false?

3. Dogs have four legs: true or false?

Now, without looking at those sentences, can you remember the last word in each sentence in the correct order? If you were able to remember them, congratulate yourself. Your working memory is like that of an average 7-year-old. This test is an example of the Listening Recall test from the Automated Working Memory Assessment. It measures verbal (auditory) working memory.

In this book, verbal working memory is synonymous with auditory working memory. In tests like this, the sentences are presented verbally and the student repeats the information out loud. In Chapter 2, we look at standardized tests to identify working memory deficits.

WHERE it is: Working memory and the brain

Brain imaging has confirmed that when we perform working memory tests, like the one in the Try It box, there is activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC also works with other areas of the brain when we use working memory. For example, when we engage in visual–spatial activities like navigating to a new restaurant, the hippocampus (the home of spatial information) is activated as our working memory draws on it to determine where we currently are, and where we need to go. When we engage in verbal information, like answering questions in a job interview, our working memory draws on ‘language centers’ such as Broca’s area, in order to craft an appropriate response.

Working memory growth

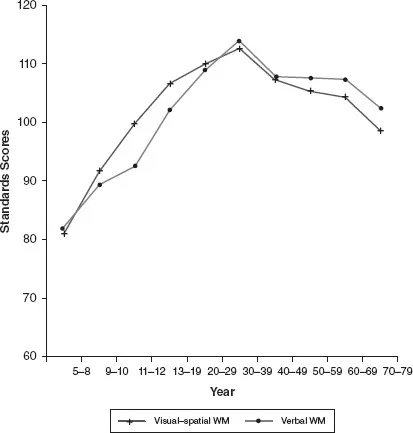

Working memory growth is closely aligned with the development of the prefrontal cortex. We conducted a study with hundreds of participants from 5 to 80 years old to find out more about how working memory grows at each age (Figure 1.1). The most dramatic growth is during childhood – working memory increases more in the first 10 years than it does over the lifespan. There is also a steady increase in working memory capacity up to our thirties. At this point, working memory reaches a peak and plateaus. The average 25-year-old can successfully remember about five or six items. As we get older, working memory capacity declines to around three to four items.

The amount of information that working memory can process at each age has important implications for the classroom. A teacher attending a seminar Tracy gave in Seattle commented that she now understood why her class found it difficult to complete what she asked them to do. Here is an example of instructions she had given to her class: Put your notebooks on the table, put colored pencils back in the drawer, get your lunchbox, and make a line by the door. Instead of forming neat lines by the classroom door after putting away their books, they would wander around the class. ‘I know why now: I would always give them four things to do at a time and it was too much for their working memory’, she said after learning about the average space we have in our working memory at each age. Here is a quick guide for tailoring classroom instructions for working memory capacity at different ages:

• 5–6 years: 2 instructions

• 7–9 years: 3 instructions

• 10–12 years: 4 instructions

• 13–15 years: 5 instructions

• 16–29 years: 6 instructions

Up until our thirties, working memory is constantly increasing in size. It is getting bigger, which means we can process more information on our mental Post-it note. But some people’s working memory grows faster than others. Think of a 7-year-old with a high working memory. Imagine a 10-year-old in a class of 7-year-olds. They are bored with what the teacher is saying and they finish assignments before anyone else. They may even act out because they have nothing else to do. This is exactly what it is like for a student with a higher working memory than his or her peers. About 10% of your class will fall in this group.

Let’s look at the other end of the scale – the student with a po...