- 648 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Global Shift is - quite simply - the definitive work on economic globalization. The extensive use of graphics, lack of jargon, and clear definition of terms has made it the standard work for the social sciences.

The Seventh Edition has been completely updated using the latest available sources. It maps the changing centres of gravity of the global economy and explains the global financial crisis. Each chapter has been extensively rewritten and new material introduced to explain the most recent empirical developments; ideas on production, distribution, consumption; and corporate governance. Global Shift provides:

- The most comprehensive and up-to-date explanation of economic globalization available, examining the role of transnational corporations, states, labour, consumers, organizations in civil society, and the power relations between them.

- A clear guide to how the global economy is being transformed through the operation of global production networks involving transnational corporations, states, interest groups and technology.

- Extended discussion of problems and institutions of global governance in the context of the global economic crisis and of the role of corporate social responsibility.

- A suite of extensive online ancillaries for both students and lecturers, including author videos, case studies, lecture notes, and free access to specially selected journal articles related to each chapter.

There is only one definitive guide to economic globalization for the social sciences: and that?s Peter Dicken?s Global Shift.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Shift by Peter Dicken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

WHAT IN THE WORLD IS GOING ON?

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The end of the world as we knew it?

Conflicting perspectives on ‘globalization’

‘Hyper-globalists’ to the right and to the left

‘Sceptical internationalists’

Grounding ‘globalization’: geography really does matter

THE END OF THE WORLD AS WE KNEW IT?

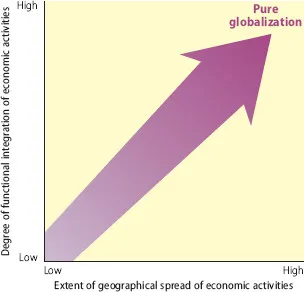

During the past 50 years the world economy has been punctuated by a series of crises. Many of these turned out to be quite limited and short-lived in their impact, despite fears expressed at the time. Some, however, notably the oil-related recessions of 1973–9 and the East Asian financial collapse of 1997–8, were very large indeed, although neither of them came close to matching the deep world depression of the 1930s. And recovery eventually occurred. Meanwhile, during the last three decades of the twentieth century the globalization of the world economy developed and intensified in ways that were qualitatively very different from those of earlier periods. In the process, many of the things we used in our daily lives became derived from an increasingly complex geography of production, distribution and consumption, whose geographical scale became vastly more extensive and whose choreography became increasingly intricate. Most products, indeed, developed such a complex geography – with parts being made in different countries and then assembled somewhere else – that labels of origin began to lose their meaning. Overall, such globalization increasingly came to be seen by many as the ‘natural order’: an inevitable and inexorable process of increasing geographical spread and increasing functional integration between economic activities (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Globalization as inevitable trajectory

And then …

On 15 September 2008, the fourth largest US investment bank, Lehman Brothers, collapsed. It was an unprecedented event, heralding the biggest global economic crisis since the 1930s. And this crisis is still ongoing. The repercussions of the financial collapse that began with the disaster of the US ‘sub-prime’ mortgage market continue to be felt throughout the world, although to widely different degrees, as we will see throughout this book. Since 2008, for example, economic growth rates (production, trade, investment) have plummeted in most of the developed world, notably in parts of Europe but also in North America. In all these cases, job losses have been huge, and the fall in incomes of the majority of the population has been so serious as to place many more people and households on the margins of survival. At the same time, the incomes and wealth of the top 1 per cent have continued to increase even more astronomically, creating enormous social tensions and an upsurge of popular resistance in many countries. The most obvious recent example is the Occupy movement, which first emerged in late 2011 as ‘Occupy Wall Street’, using ‘We are the 99%’ as its rallying cry. In comparison, some developing countries – the so-called ‘emerging markets’ – have experienced relatively high growth rates, leading some observers to talk of the emergence of a ‘two-speed world economy’. But that broad-brush picture, though valid in some respects, masks continuing and deep-seated issues of poverty and deprivation throughout the world. The notion that developing countries can somehow ‘decouple’ from the effects of financial crisis in developed countries is demonstrably far from the truth.

To individual citizens, wherever they live, the most obvious foci of concern are those directly affecting their daily activities: making a living, acquiring the necessities of life, providing the means for their children to sustain their future. In the industrialized countries, there is fear – very much intensified by the current financial crisis – that the dual (and connected forces) of technological change and global shifts in the location of economic activities are adversely transforming employment prospects. The continuing waves of concern about the outsourcing and offshoring of jobs, for example in the IT service industries (notably, though not exclusively, to India), or the more general fear that manufacturing jobs are being sucked into a newly emergent China or into other emerging economies, suddenly growing at breakneck speed, are only the most obvious examples of such fears. Such fears are often exacerbated by concerns about immigration, especially among lower-skilled workers who perceive, correctly or incorrectly, a double squeeze of jobs moving abroad and those at home being taken by immigrants on low wages. But the problems of the industrialized countries pale into insignificance when set against those of the very poorest countries. The development gap persists and, indeed, continues to widen alarmingly.

Hence, the world continues to struggle to cope with the economic, social and political fallout of the unravelling of the global financial system which occurred with such sudden, and largely unanticipated, force in 2007–8. The spectacular demise of Lehman was only one of many casualties. But its collapse was highly symbolic. Lehman was one of those institutions that epitomized the neo-liberal, free market ideology (sometimes known as the ‘Washington Consensus’) that had dominated the global economy for the previous half century. This was the ideology of so-called free and efficient markets: that the market knew best and that all hindrances to its efficient operation – especially by the state – were undesirable. But in 2008, all this was suddenly thrown into question. As one financial institution after another foundered, as governments took on the role of fire-fighters, and as several banks became, in effect, nationalized, the entire market-driven capitalist system seemed to be falling apart.

Question: does the economic turmoil that broke out in 2008 herald ‘the end of the world as we knew it’, ‘the end of globalization’? Well, it all depends on what we mean by ‘globalization’: it is important to distinguish between two broad meanings of the term:1

• One is empirical. It refers to the actual structural changes that are occurring in the way the global economy is organized and integrated.

• The other is ideological. It refers to the neo-liberal, free market ideology of the ‘globalization project’.

These two meanings are often confused. Of course, they are not separate but it is important to be aware of which meaning is being discussed.

It is too early to say whether the free market ideology has been irrevocably changed by the global financial crisis. Some think it has. Many more think it should be. Others believe that, once the dust finally settles, it will be business as usual. That may, or may not, be the case. But globalization, as we will see throughout this book, has never been the simple all-embracing phenomenon promulgated by the free market ideologists. We need to take a much more critical and analytical view of what is actually going on over the longer term; to move beyond the rhetoric, to seek the reality. That is one of the primary purposes of this book.

CONFLICTING PERSPECTIVES ON ‘GLOBALIZATION’

Globalization is a concept (though not a term) whose roots go back at least to the nineteenth century, most notably in the ideas of Karl Marx. Indeed, in the light of the post-2008 crisis, many observers – even some who could by no stretch of the imagination be regarded as ideologically on the left – recognize that Marx’s analysis of the development of global capitalism2 was extremely acute and highly relevant to today’s world. ‘Globalization’ as a term entered the popular imagination in a really big way only in the last four decades or so. Now it is everywhere. A perusal of Web-based search engines reveals millions of entries. Hardly a day goes by without its being invoked by politicians, by academics, by business or trade union leaders, by journalists, by commentators on radio and TV, by consumer and environmental groups, as well as by ‘ordinary’ individuals. Unfortunately, it has become not only one of the most used, but also one of the most misused and one of the most confused terms around today. As Susan Strange argued, it is, too often,

a term … used by a lot of woolly thinkers who lump together all sorts of superficially converging trends … and call it globalization without trying to distinguish what is important from what is trivial, either in causes or in consequences.3

‘Hyper-globalists’ to the right and to the left

Probably the largest body of opinion – and one that spans the entire politico-ideological spectrum – consists of what might be called the hyper-globalists,4 who argue that we live in a borderless world in which the ‘national’ is no longer relevant. In such a world, globalization is the new economic (as well as political and cultural) order. It is a world where nation-states are no longer significant actors or meaningful economic units and in which consumer tastes and cultures are homogenized and satisfied through the provision of standardized global products created by global corporations with no allegiance to place ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Praise for Global Shift

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- About the Author

- Preface to the Seventh Edition

- About the Companion Website

- 1 What in the World Is Going On?

- Part One The Changing Contours of the Global Economy

- Part Two Processes of Global Shift

- Part Three Winning and Losing in the Global Economy

- Part Four The Picture in Different Sectors

- Bibliography

- Index