- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The CBT Handbook

About this book

The CBT Handbook is the most comprehensive text of its kind and an essential resource for trainees and practitioners alike. Comprising 26 accessible chapters from leading experts in the field, the book covers CBT theory, practice and research.

Chapters include:

- CBT Theory

- CBT Skills

- Assessment and Case Formulation in CBT

- The Therapeutic Relationship in CBT

- Values and Ethics in CBT

- Reflective and Self-Evaluative Practice in CBT

- Supervision of CBT Therapists

- Multi-disciplinary working in CBT Practice

This engaging book will prove an indispensible resource for CBT trainees and practitioners.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The CBT Handbook by Windy Dryden, Rhena Branch, Windy Dryden,Rhena Branch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

CBT: Practice

| ONE | What Is CBT and What Isn’t CBT? |

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of CBT and its current application within health and social care services in the UK. The defining features of CBT are described in terms of its underpinning principles. A multilevel definition of CBT is set out that incorporates its theoretical underpinnings, the evidence base, treatment techniques and paradigms, therapist competencies and practice, and service delivery and contexts. How CBT can be distinguished from non-CBT interventions is then considered. Finally, some of the future challenges and directions for the development of CBT are outlined.

What is CBT?

‘We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts we make the world.’

Buddha (Hindu Prince Gautama Siddharta, the founder of Buddhism, 563–483 BC)

‘Man is not moved by things but by the view that he takes of them’

Epictetus (The Enchiridion, AD 135)

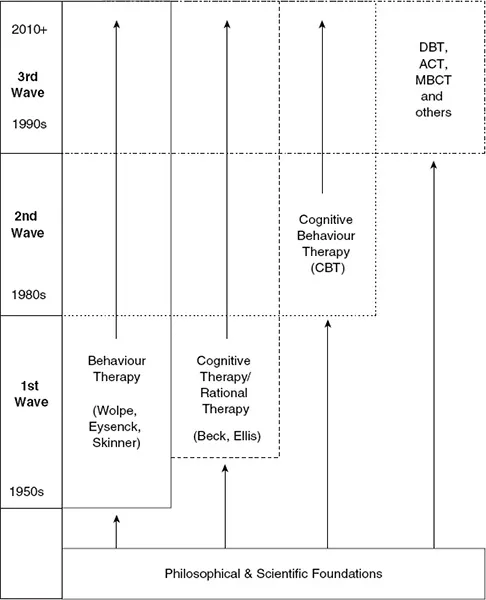

It can be seen in the quotes above that the conceptual roots of CBT can be traced to philosophies from both Western and Eastern origins (Gilbert, 2010). Yet, the term Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) only came in to being during the 1970s (e.g. Taylor & Marshall, 1977). Figure 1.1 illustrates the development of CBT since its inception.

Figure 1.1 A simplified diagram of the development of CBT (for a more elaborate diagram, see Mansell, 2008a). The vertical column on the left represents a timeline from 1950s at the bottom to the present day, with the timings of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd waves of CBT demarcated. The extent to which each new wave builds on, and coexists together with the previous waves, is demonstrated by the overlapping blocks. The continuing revisiting of philosophical and scientific influences is illustrated by the upward arrows.

The movement began in the 1950s, when the scientific bases of cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy were developed – commonly known as the ‘first wave’ (Rachman, 1997). The key figures in the development of behaviour therapy are commonly regarded as the psychologists Joseph Wolpe, Hans Eysenck and B.F. Skinner (e.g. Wolpe, 1958). Behaviour therapy based its approach around theories of how learning new ‘associations’ between experiences (classical conditioning) and between experiences and behaviour (operant conditioning) could be reproduced in patients with psychological problems who have had learned counterproductive behaviours after a history of aversive or traumatic experiences. At around the same time, two psychoanalysts – Aaron T. Beck (a psychiatrist) and Albert Ellis (a psychologist) – were developing cognitive therapy and rational therapy, respectively (Beck, 1963; Ellis, 1962). Both approaches identified the role of biases in current thinking styles (e.g. catastrophising; following ‘must’ rules) that developed from earlier experiences and which contribute to current psychological distress. They brought in methods to address them based on a collaborative relationship, open questioning and testing beliefs against the real world (which will be elaborated later).

After a decade or so of these approaches developing separately, the ‘second wave’ led to their fusion as CBT that took prominence in the 1980s. According to Rachman (1997), this resulted from the increasing common ground between the two approaches – behaviour therapists became increasingly aware of the limitations of pure learning theory and the advantages of cognitive science; cognitive therapists incorporated the behavioural emphasis on empiricism into their evaluation of the therapy through objective and statistical methods. Arguably, the classic example of this integration within CBT is the behavioural experiment (Bennett-Levy et al., 2004) – a method whereby a controlled situation is created in which the client tries out a new way of behaving and then collects evidence to see whether their beliefs are found to be supported or disconfirmed. One example is a client with panic disorder who is afraid of having a heart attack and so sits down whenever he feels exerted. In the behavioural experiment, the client tries out standing up rather than sitting down and discovers that he does not have a heart attack – this intervention combines the precision of a behavioural account with a locus of change – a ‘belief’ about imminent danger – that is cognitive.

During the time that the second wave was gaining momentum, the seeds of a ‘third wave’ were sown. Now, since the 1990s, we have seen the development of this third wave of CBT, for example Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2002), and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999). These third wave therapies have been developed by revisiting and integrating diverse theoretical and therapeutic and philosophical influences such as attachment theory, meditation and radical behaviourism (Mansell, 2008b). The third wave approaches differ from one another to some degree, yet arguably share an emphasis on a ‘mindful states of awareness’, which we shall discuss later. Potentially, this results in CBT lacking coherence in its theories, principles and techniques because all three waves of CBT now coexist in services (Mansell, 2008a). The newer forms of CBT can appear on the face of it somewhat different as they use a diverse range of new terms, tools and techniques. In the following section we illustrate that, despite these differences, CBT can still be clearly distinguished as an entity in three distinct if overlapping ways:

- Through the underpinning principles of CBT (the collaborative relationship, prioritising the present, empiricism and rationalism) that are shared across its various forms.

- Through a multilevel definition of CBT that incorporates principles, theory, evidence, service delivery and context, therapist competencies and practice, tools and techniques, and the present moment during therapy itself.

- Through what a CBT client would experience in therapy sessions.

The Principles of CBT

CBT can be most clearly distinguished in terms of its core principles which remain relatively constant across the wide range of behavioural and cognitive therapies that are available. The principles of CBT are evident in the way that it is practised rather than in any specific technique, or indeed any specific psychological theory. These principles include the following.

The Collaborative Relationship. In many non-CBT therapies, the relationship between client and therapist is seen as the main agent of change. In CBT, the client and therapist working together is seen as an essential necessary condition to practise CBT. However it is not generally regarded as sufficient to bring about change in most cases. The collaborative relationship in CBT involves the client and therapist working together to try to understand the client’s problems and the process of recovery. This approach has also been termed ‘guided discovery’. Both therapist and client bring essential information to the session – the client brings their experiences and insights, and the therapist brings their therapeutic skills and their scientific-practitioner approach. CBT does not utilise the kind of expert–patient relationship that characterises many other interactions between patients and health professionals. For example, in behavioural therapy for a specific phobia, the therapist and client work together to produce a step-by-step ‘graded hierarchy’ for the client to face his or her fears. The first step on the hierarchy would be chosen by the client. For example, a bird phobic may choose to look at a photograph of a bird as a first step. Even in third-wave CBT, the development of a collaborative therapeutic relationship remains central.

Prioritising the Present. CBT is focused on working with the client on his or her present problems. Some CBT therapies acknowledge the importance of understanding how past experiences shape present beliefs, behaviours and thinking. Good practice requires, and the competencies of CBT therapists include, the ability to undertake a careful personal history, including significant previous experiences and events, with the aim of helping the client to focus on present concerns and how they can be more effectively managed. The importance of the present moment is clear in techniques such as ‘thought catching’, in which the client is helped to notice the thoughts that pass through their mind as they occur. Also, when clients are confronting their fears in therapy, the focus is on the current feelings of anxiety, in order to help them to tolerate them better and to illustrate how the intensity of the emotion reduces over time. Within third-wave therapies, for example MBCT, the client learns to focus on their breathing as it is occurring and the thoughts that appear in the present moment.

Empiricism. This is the view that personal beliefs are based on evidence gathered from our senses. This philosophy is often considered to mark the beginning of the culture of scientific thinking in the seventeenth century. Famously, Sir Francis Bacon told a parable about a long argument between two friars over the number of teeth in a horse’s mouth. This was settled eventually by the use of direct evidence – actually counting the teeth. Arguably, CBT empowers clients to use an empirical approach for themselves; to test for evidence against their long-held beliefs and assumptions (e.g. ‘I need to please other people all the time to be worthwhile’) rather than to simply accept them as true. The principle of empiricism in CBT also guides the way that clients are encouraged to test out their beliefs and the effects of their thinking styles and behaviours in the real world. Classically, this is achieved through ‘behavioural experiments’ (Bennett-Levy et al., 2004). A behavioural experiment can be used not only to test the evidence for a particular belief, but to evaluate the effects (advantages vs. disadvantages) of any cognitive or behavioural process utilised in the light of evidence. This metacognitive aspect of therapy underpins many contemporary innovations in CBT (e.g. Wells, 2000; Watkins, 2008). CBT also utilises empiricism in evaluating its own effectiveness. The therapist monitors the outcomes in individual clients; services evaluate their outcomes across multiple clients; and the theories underpinning CBT are tested against evidence in research studies.

Rationalism. This refers to the notion that one’s feelings have an origin in one’s thinking. This is often mistaken for a view that being ‘rational’ is a virtue in itself, and that we need to train people to be logical thinkers. This is not quite accurate. Rationalism is based on a philosophy in which the explanation for one’s feelings and behaviour lies in one’s thinking. It is because one believes something to be true – whether or not it is in fact true – that affects one, rather than there being some unknown cause. The philosophical roots of rationalism are longstanding – going back, for example, to the Stoic movement of Ancient Greece, stated at the start of the chapter in the quote by Epictetus. This principle can be seen clearly in most CBT approaches. For example, CBT for panic disorder helps people to understand that it is their beliefs about the harmful effects of their bodily sensations (e.g. believing that an increased heart rate signals a heart attack) that is driving a panic attack. Within ACT (e.g. Hayes et al., 1999) the client learns to see how he is equating a thought about an event (e.g. ‘I might hit my baby’) with the event itself, and is helped to ‘defuse’ thoughts from events using a variety of techniques.

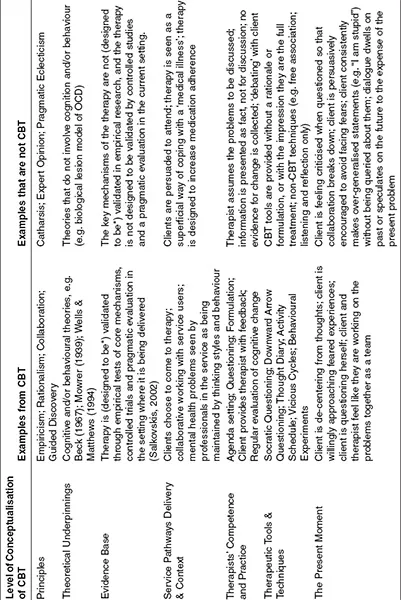

A Multilevel Definition of CBT

In addition to the core principles of CBT described above, there are other levels at which we can conceptualise CBT. Table 1.1 describes these levels and gives examples that are CBT and non-CBT. Importantly, if a psychological therapy is provided that is not consistent with the features of CBT at one of these levels, it seriously compromises the extent to which that therapy can be labelled CBT. This is an issue that deserves consideration in the present climate in which the term ‘CBT’ has become so widespread – much more widespread than the valid practice of CBT.

The levels are described in further detail here:

Principles of CBT. This level of definition is arguably the most consistent, as described above.

Theoretical underpinnings. The British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) defines CBT as follows: ‘The term “Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy” (CBT) is variously used to refer to behaviour therapy, cognitive therapy, and to therapy based on the pragmatic combination of principles of behavioural and cognitive theories.’ (BABCP, 2005). While the principles described above are shared among nearly all forms of CBT, they do differ in terms of the psychological theories underpinning them. Generally, the underpinning theories are behavioural or cognitive in nature, but it is accepted that even these theories have origins in a range of sources including attachment theory, developmental psychology, and social psychology (Mansell, 2008b). With the advent of third wave therapies, there has been further importation of theoretical frameworks, many of which have their grounding in behavioural and cognitive approaches. Thus, while the principles of CBT are clear and relatively consistent across all forms of CBT, the theoretical underpinnings are diverse and require a consensual framework that integrates the principles and practice of CBT.

Table 1.1 A Multilevel Definition of CBT

*CBT is designed for these forms of evaluation but may be in the process of validation through these multiple stages at the time of use.

Evidence base. Much has been written and said about the evidence base supporting the effectiveness of CBT for mental health problems. It is important to consider the different elements of a robust evidence base. First, the scientific support for CBT involves reciprocal links between theory, practice, clinical observations and research (Salkovskis, 2002). This involves a wide range of empirical studies testing the theories that underpin CBT including experimental studies, diary studies, interviews, and longitudinal studies exploring the long-term impact of interventions. Without this, it is impossible to be sure that a therapy works through the mechanisms proposed by the theory. Second, the real proof of the impact of CBT has emerged in its use in routine clinical settings, and more specifically by the individual clinician who uses the empirical method to evaluate his or her own CBT practice. Third, if CBT has a stronger evidence base than therapy x, this does not mean that CBT is more ef...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Editor and Contributor Biographies

- Editors’ Introduction

- Part 1 – CBT: Theory

- Part 2 – CBT: Practice

- Part 3 – CBT: Common Challenges

- Part 4 – CBT: Specific Populations and Settings

- Part 5 – CBT: Professional Issues

- Index