![]()

| Issues and processes in management research | Part I |

![]()

Learning outcomes At the end of this chapter the reader should be able to:

- appreciate the complexity of management research and some of the controversies and developments that are encouraging methodological diversity;

- begin to understand the impact of the researcher’s philosophical commitments upon the choice of methodological approach;

- understand the difference between deduction and induction in research methodology;

- appreciate the relationship between management research and management development;

- understand the aims, structure and content of this book.

In this chapter preliminary consideration is given to the complexities of management as a field of study and its increasing methodological diversity. Within this context, management research is clarified as a process by comparing and contrasting it with management development. The chapter also introduces the two main, yet often competing, approaches to management research that articulate competing philosophies – induction and deduction. The philosophical rationales underpinning these alternatives are further explored throughout the book, especially so in Chapter 3, and their varying methodological expressions give a framework for our examination of different research methods throughout subsequent chapters. Chapter 1 concludes by providing an outline of the structure of the rest of the book and the content of those chapters.

Innovation and diversity in management research

Management research is a complex and changing field which demonstrates several interrelated tendencies. In order to understand these developments it is initially helpful to place management research in some historical context. Some 25 years ago, in a discussion of the historical development of management studies, Whitley (1984a, b) described it as being in a fragmented state; as a field characterized by a high degree of task uncertainty and a low degree of co-ordination of research procedures and strategies between researchers who undertake research in an ad hoc and opportunistic manner. This apparent situation led Pfeffer (1993, 1995) to argue, by using economics as an exemplar to be copied, that management research must develop consensus through the enforcement of theoretical and methodological conformity. As he argued, such a paradigmatic convergence may increase the social standing of the discipline and thus should assure more access to scarce resources, whilst easing its methodological development. However, in a reply to Pfeffer, Van Maanen (1995a) argued that if management research followed Pfeffer’s recommendations the resultant enforced conformity would create what amounted to a ‘technocratic unimaginativeness’ which could drive out tolerance of the unorthodox and significantly reduce our learning from one another. During the intervening years, management students have been confronted by much controversy about the most appropriate approaches to the study of management as an academic discipline. Of course, it is debatable how far these controversies have actually reconfigured management research practice as it may be argued that there is a dominant orthodoxy within management research which is maintained by very powerful institutional pressures. Nevertheless, the dominance of this mainstream in management research is being resisted by numerous management researchers and indeed has been under attack on a number of fronts (see Symon et al., 2008). To some extent the development of these controversies has been due not only to the emergence of different schools of management thought but also to the development of different approaches to research methodology, especially so in the social sciences. Indeed, since the first edition of this book in 1991, there seems to have been an increasing methodological diversity amongst those who undertake what can be broadly classified as management research – although it is important to note that quantitative methods still dominate much of what is published in prestigious academic journals.

Whilst it remains accurate to say that the diversity in management research has been exacerbated due to its multi-disciplinary (Brown, 1997) and inter-disciplinary (Watson, 1997) nature and its position at the confluence of numerous social science disciplines (e.g. sociology, psychology, economics, politics, accounting, finance and so on), other forces are clearly at play which have promoted methodological innovation and change. For instance, this increasing diversity might also be explained by the ‘coming of age’ of qualitative and interpretive methods (see Prasad and Prasad, 2002) which may be seen as arising in response to certain perceived limitations in conventional management research and thereby presents a significant challenge to, and critique of, the quantitative mainstream of management research. However, qualitative management research is itself characterized by an expanding array of methodologies that articulate different, competing, philosophical assumptions which have significant implications for how management research should be (Johnson et al., 2006), and is (Johnson et al., 2007), evaluated by interested parties. Simultaneously, there has been the development of an array of critical approaches to the study of management usually going under the umbrella term ‘critical management studies’. This influential development, in part, arises out of a philosophical and methodological critique of the assumed objectivity and neutrality of the quantitative mainstream but also aims to generate what are presented as emancipatory forms of research that challenge the status quo in contemporary organizations by exposing and undermining dominant managerial discourses whose content is often just taken-for-granted by organizational members and thereby assumed to be natural and unchallengeable (see Fournier and Grey, 2000; Grey and Willmott, 2005; Kelemen and Rumens, 2008). Of course such developments open questions about who is the intended audience for management research. For instance, is management research about:

- addressing the presumed pragmatic concerns and presumed business needs of practising managers, or,

- is it about investigating and understanding the structures and processes of oppression and injustice, that are taken to be part of organizing in a capitalist society, whose main beneficiaries and victims are often these social actors labelled managers?

Any cursory inspection of management research would suggest that a great deal of it published in prestigious academic journals adopts, often by default, the first orientation noted above. Unlike our second orientation above, it adopts the view that management research must be relevant in the sense that it helps managers to manage more efficiently and effectively by enhancing their ability to cope with the problems that assail contemporary organizations by improving the technical content of managerial practice based upon rigorous analysis using social scientific theory rather than common sense. However, many commentators (e.g. Tranfield and Starkey, 1998; Keleman and Bansal, 2002) have noted some irony here in the sense that the channels by which this research is disseminated, and often the language used, all tend to reflect the institutional incentives, intellectual requirements, interests, and concerns of academia rather than the needs of management practitioners, whoever they might be. Nevertheless, many management researchers (e.g. Heckscher, 1994; Osbourne and Plastrik, 1998; Kalleberg, 2001; Johnson et al., 2009) have pointed to how the nature of managerial work, and the roles available to managers, may indeed be fundamentally changing under the impact of the organizational changes driven by a possible shift from bureaucratic forms of command and control to post-bureaucratic forms of organizational governance. The latter are usually characterized as flatter, less hierarchical, more networked and flexible organizations wherein employees are necessarily empowered to use their discretion to cope with a more volatile and uncertain workplace and requires managers capable of facilitating the participation of self-directed employees in decision-making (Tucker, 1999): something which further requires the evolution and deployment of managers’ research skills at work (Hendry, 2006).

Of course the second orientation noted above is much more associated with critical management studies, which often overtly rejects a managerially orientated approach partially on the basis of a desire to enhance the democratic rights and responsibilities of the relatively disempowered majorities of members of work organizations: an approach that has significant methodological implications but which also is an outcome of a philosophical challenge to mainstream management research (which we shall consider later in this book) which seems to reflect Whitley’s (1984b: 387) criticism that management research had adopted ‘a naïve and unreflecting empiricism’. For Whitley, the solution to this problem required freeing researchers from lay concepts and problem formulations and by providing them with a more sophisticated understanding of the epistemological and sociological sciences.

In sum, there are a range of forces at play which have created a trajectory in management research that seems to be one of increasing methodological diversity and innovation, much of which uses varying philosophical critiques of the quantitative mainstream as a starting point to legitimate the methodological changes that are deemed to be necessary.

One of the major themes of this book is that there is no one best methodological approach but rather that the approach most appropriate for the investigation of a given research question depends on a large number of variables, not least the nature of the research question itself and how the researcher constitutes and interprets that question. Research methodology is always a compromise between options in the light of tacit philosophical assumptions, and choices are also frequently influenced by practical issues such as the availability of resources and the ability to get access to organizations and their memberships in order to undertake research.

Making methodological choices

In this book we will advance criteria for choice of methodology by reviewing the major approaches to management research and, through examples, their appropriateness to finding answers to particular research questions. Therefore, one key aim of this work is to illustrate the different means by which business and management research is undertaken by presenting some of the variety of methodologies that are potentially available to any researcher. In attempting to meet our key aim we are also concerned to illustrate that the research methods available to the management researcher are not merely neutral devices or techniques that we can just ‘take off shelf’ to undertake a particular task for which they are most suited. Such a perspective implies that it is the nature of the research question, and what phenomenon is under investigation, which should pragmatically dictate the correct research method to use since different kinds of information about management are most comprehensively and economically gathered in different ways. Whilst at first sight this stance seems to have much to offer, and of course the nature of the research question being investigated is methodologically important, it can simultaneously deflect our attention from what we see to be a key issue: that the different research methods available to the management researcher also bring with them a great deal of philosophical baggage which can remain unnoticed when they are classified as constituting merely different data collection tools that can be chosen to do different jobs. Therefore, management researchers need to be aware of the philosophical commitments they make through their methodological choices, since that baggage has a significant impact not only upon what they do, but also upon how they understand whatever it is that they think they are investigating in the first place.

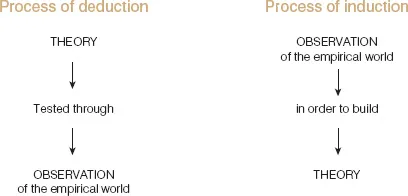

For instance (see Figure 1.1), the decision to use deductive research methods (for example, experiments, analytical surveys, etc.) that are designed to test, and indeed falsify, previously formulated theory through confronting its causal predictions about human behaviour with empirical data gathered through the neutral observation of social reality, tacitly draws upon an array of philosophical assumptions and commitments that are contestable yet so often remain taken-for-granted. Even a cursory inspection of the management field would show that such methodological choices are common place yet, by default, also involve the decision not to engage through alternative means: alternatives that in themselves articulate different philosophical commitments, e.g. to build theory inductively out of observation of the empirical world that focuses upon the operation actors’ everyday culturally derived subjective interpretations of their situations in order to explain their behaviour theoretically. As we will see in Chapter 3, there are significant philosophical differences between these two approaches, to a degree initially centred upon what each assumes to be the key influences upon human behaviour and the forms that it takes as well as how those influences are best investigated by researchers.

Figure 1.1 Deduction vs induction

The point is that whilst we cannot avoid making philosophical commitments in undertaking any research, a problem lies in the issue that any philosophical commitment can be simultaneously contested because they are merely assumptions that we have to make. This is because the philosophical commitments which are inevitably made in undertaking research always entail commitment to various knowledge-constituting assumptions about the nature of truth, human behaviour, representation and the accessibility of social reality. In other words there are always tacit answers to questions encoded into what is called the researcher’s pre-understanding. These answers are:

- about ontology (what are we studying?)

- about epistemology (how can we have warranted knowledge about our chosen domains?)

- and about axiology (why study them?).

Those answers always have a formative impact upon any methodological engagement. Quite simply we cannot engage with our areas of interest without having answers already to those questions. The philosophical assumptions we make in dealing with these questions implicitly present different normative specifications, justified by particular rationales, for management research reg...