![]()

PART ONE

FAMILY

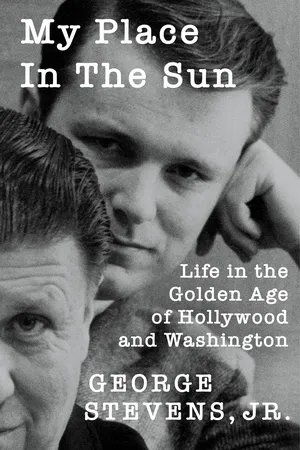

Landers Stevens’ theatrical company performing Lead, Kindly Light in San Francisco, circa 1914. Landers, left in white hat, his wife Georgie Cooper, center. George Stevens, Sr., age ten, kneeling far left. Jack Stevens, age eleven, holding newspapers, right.

![]()

1

San Francisco

A fog-shrouded September night in 1900.

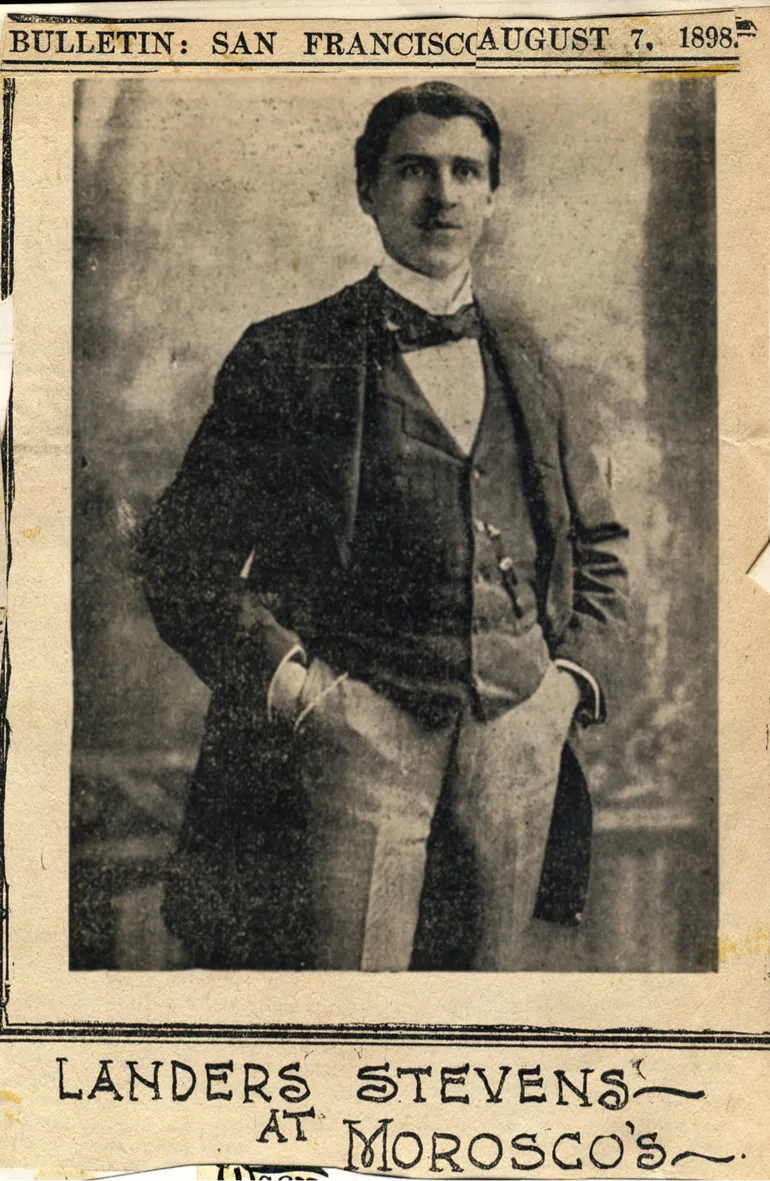

Landers Stevens was the last to leave the Dewey Theater on Twelfth Street in Oakland, the town of his birth. He secured the doors, packed the receipts in his pouch, and bid the watchman goodnight. Landers was just twenty-four but the playbill from the day lists him as “Proprietor and Manager” of the Dewey, where he directed the plays and was the company’s leading man. Tall and square-jawed, always carefully dressed, he set off briskly down Broadway to catch the last ferry across the bay to San Francisco.

When he turned onto Fourteenth Street two toughs sprang from the darkness and tackled him. As the San Francisco Call reported the next day, “One of the robbers struck him a powerful blow on the face at the point of the jaw, staggering Landers and nearly knocking him insensible.” He gathered himself, threw off one of the men, managed to draw his pistol, and “beat down the assailant with a half-dozen blows on the face with the clubbed weapon.” Nursing a severely cut hand and a swollen jaw, Landers told the Call reporter that it was the hardest battle he ever fought. “While I was fighting the man whom I captured, the first man recovered and ran. I didn’t want to take a chance of killing him so I did not fire.”

John Landers Stevens was my grandfather. He was the younger son of James William and Hannah Laura Stevens. James came to San Francisco from Maryland in the 1850s with his parents and five brothers and sisters. He became a businessman and met Hannah Laura Thompson, who came west across the Sierras in a covered wagon from Liberty, Missouri, propelled by whatever dreams drove pioneers to make that grueling journey. James and Hannah Laura fell in love, were married, and fostered the Stevens family.

A few years after his encounter with the robbers, Landers sat in a darkened theater and watched an ingenue, a tall girl with fine features and a lilting soprano, perform in an operetta. He waited at the stage door and introduced himself to Georgie Cooper, undertook a courtship, and asked her to marry him—a proposal that proved pivotal to my own existence.

Landers Stevens at age twenty-two on the stage of Morosco’s Grand Opera House in San Francisco, 1898.

I knew Landers as an older man, with lines of silver showing through his black hair, living in a small house in Glendale where I would sleep on the living room sofa. He and my grandmother Georgie were then in their sixties and there were few signs of a glamorous past. But my mother, who became our family’s informal archivist, left me a copy of their wedding license along with a note in her handwriting.

Landers was married to Fannie Gillette (sister of Gillette Razor) and she got a divorce so he could marry Georgie. They drove all night from San Francisco to San Jose after the show—were married at 9:05 a.m. and drove back to S.F. to do the show that night.

A yellowed clipping from a San Jose newspaper, dated April 20, 1903, supports my mother’s account:

John Landers Stevens, the actor, who was divorced in San Francisco yesterday, was remarried in this city today by City Justice Davidson to Miss Georgie Cooper, the soubrette at the Central Theater. Thomas McGoeghegan, city treasurer, was best man. The bride was attended by her maid. Eighteen year old Georgie is a second generation actress whose mother, Georgia Woodthorpe, is an audience favorite on San Francisco stages.

It was Georgia Woodthorpe, my great-grandmother, who launched five generations (and counting) of Stevens family participation in the entertainment world. She was born in San Francisco in 1859, when the Gold Rush town was becoming a cosmopolitan city. Her father loved amateur theatricals, and one afternoon J. B. McCullough, a noted impresario and one of the leading tragedians of the American stage, heard five-year-old Georgia recite an “impromptu entertainment” in the basement of the Actors Club. He persuaded her parents to let her join his company and she made her debut as young Prince Arthur in Shakespeare’s King John at the California Theater. McCullough, a broad-shouldered man with a large head and strong features, played Falconbridge. “When he carried me—presumably dead—on to the stage,” Georgia remembered, “his extended arms shook and his tears fell on my face.” McCullough complimented her afterward: “The unconscious acting of childhood . . . Little Girl, you’ll never know how great you were.”

When she was seventeen Georgia fell in love with a schoolmate called Billy Wallace, an attraction so intense that in 1877 they ran off to Santa Clara and married. When they returned to San Francisco their incensed parents were waiting. Billy’s father doubted the stability of marriage to an actress, and the Woodthorpes believed marriage would constrain Georgia’s promising career, so they insisted on an immediate annulment. The tearful lovers parted and young Billy Wallace left the Bay Area to make his life in Oregon.

Georgia became a celebrated leading lady in San Francisco. She married Fred Cooper, an actor and manager, and they lived a theatrical life, touring across the United States, while finding time to have three daughters. The first, my grandmother Georgie Cooper, was born while her mother was playing in Battle Creek, Michigan. A second daughter was delivered in a Utah train station, earning her the name Edith Ogden Cooper. The third sister, Olivette, became an actress and a longtime screenwriter at Republic Pictures.

Great-grandmother Georgia shared the stage with the most commanding figures of American theater, including Lawrence Barrett, McKee Rankin and Charles Fechter. When she was only seventeen, she played Ophelia to Edwin Booth’s Hamlet in San Francisco. Booth was considered America’s greatest ever Hamlet, and in an era when theater was king, America’s brightest star. Yet he bore the stigma of being the brother of Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, actor John Wilkes Booth. Georgia, the youngest ever to play Ophelia opposite Booth, observed her Hamlet after a matinee complaining about being hungry, and ordering his dresser to run across the street and bring him food. “I stood outside his dressing room staring at the unexpected sight of the great Booth drinking beer and eating bologna.” Booth noticed her and laughed, “Ah, Little Girl. Someday when you’ve done one big performance and are facing another, you’ll know how good these are.” Georgia’s only comment: “I thought he would at least have champagne and truffles.”

Georgia Woodthorpe enjoyed a distinguished career on the stage but in later years her life took an unusual turn, documented in a yellowed clipping I have from the August 15, 1919, Morning Oregonian. After the death of her husband Fred Cooper, Georgia continued performing and was touring in a play in Portland, Oregon. One night there was a knock on her dressing room door. It was Bill Wallace (no longer Billy), now an Oregon businessman, twice married and twice divorced. The two hadn’t spoken or corresponded since the day of their annulment forty years earlier. Bill repeated his proposal of marriage and the two were wed. “Love’s Fires Banked, Burst Forth Afresh,” proclaimed the Oregonian. “Even willful fate cannot thwart two schoolmate lovers who insist on having things their own sweet way.”

However heartwarming the story of Billy and Georgia may be, I must consider that were it not for that forced annulment in 1877, my great-grandmother Georgia would not have married Fred Cooper and given birth to Georgie Cooper, and Georgie would not have produced my father George—and the Stevens family as we know it would not exist.

My grandmother Georgie made her debut in the theater at age ten. Dr. David Burbank, a wealthy dentist, became such a fan of her mother that he built the Burbank Theater in Los Angeles for Georgia Woodthorpe to star in and for her husband to manage and promote. A columnist described Fred Cooper driving a pair of zebras down Main Street to generate attention for the theater’s 1893 opening in which little Georgie played the title role in Little Lord Fauntleroy alongside her mother. The little girl so enjoyed the glow of footlights that by the time the family returned to San Francisco the stage was her calling too.

Grandmother Georgie Cooper at the Alcazar Theater, San Francisco, circa 1903.

Georgie Cooper in the classic velvet Fauntleroy suit she wore in her debut at the Burbank Theater in Los Angeles in 1893.

It was ten years later that Landers and Georgie married and started their own stock company at Ye Liberty Playhouse in Oakland, where they performed Shakespeare and Dickens and the new plays of the day.

Georgie gave birth to my Uncle Jack, John Landers Stevens, Jr., on November 2, 1903. The date sheds light on the hurried aspect of the wedding in San Jose just seven months before. George Cooper Stevens, my father, was born on December 18, 1904, which happened to be the year the nickelodeon made its debut in New York—the device that would soon disrupt his parents’ livelihood and, in time, provide one for him.

As the twentieth century blossomed, artists came from around the world to perform in San Francisco. The legendary Enrico Caruso arrived from Italy with considerable fanfare to sing Don José in Bizet’s Carmen at the Grand Opera House on April 17, 1906. Georgie and Landers were playing at the Ye Liberty and returned to their hotel in San Francisco after their show. My father was fourteen months old, sleeping in a bassinet on wheels, when at 5:12 a.m. the city began to shake. The Great San Francisco Earthquake sparked fires that burned twenty-nine thousand buildings to the ground and left three hundred thousand residents homeless, including the Stevens family. The great Caruso survived the quake but the Palace Hotel where he was staying did not, and the beloved tenor fled the city the next morning vowing never to return—a pledge he honored.

Half a century later Georgie Cooper Stevens described that fateful night to my mother. “The whole front of the building collapsed,” she said, “and I grabbed the bassinet and just held on.” When my mother heard the story for the first time in middle age, her Irish humor took over. “If you’d have let that bassinet go you would have saved me a whole lot of trouble.”

In their teens Landers and his older brother Ashton followed their parents into the theater world. Ashton mastered the banjo by nineteen and was giving lessons at home for a dollar and a half, working upstairs with his customers. He paid Landers, then fourteen, five cents to ring the doorbell and inquire about lessons in such a loud voice that Ashton’s students and their parents would hear. Each time he simulated a different voice and manner. “That’s how I got the acting bee,” Landers explained. The publisher William Randolph Hearst hired Ashton for banjo lessons, took a shine to his young instructor, and gave him a job at the San Francisco Examiner. Ashton gained a tryout as drama critic. “I expect excellence,” Hearst told him, with a reminder that two of his predecessors, Ambrose Bierce and Bret Harte, were in the pantheon of American writers. Hearst liked Ashton’s conversational style of criticism and sent him east to be drama critic at the New York Evening Journal.

My great-uncle Ashton believed critics should write about plays just as they would about the weather—“showing hardly any regard for the weather’s feelings.” He applied this principle even to his brother’s performances. Landers claimed that Ashton’s reputation for honesty was acquired at his expense. When readers saw Ashton’s criticism of Landers’ Hamlet or Sherlock Holmes, they would say, “He must be on the level, he pans his own brother.”

Landers was mentored in his teens by Frederick Warde, one of the most admired actors of the day. He was invited on Warde’s national tour during which he compiled critics’ notices in scrapbooks with praise of his performances underlined in red. One review in New York criticized Warde’s star performance in Runnymede and singled out Landers for the only piece of creditable acting, perhaps straining the mentorship. Landers returned to San Francisco at twenty and was chosen to be leading man at the Alcazar. “He acts with an earnestness and finish and a degree of naturalness that are as agreeable as it is rare,” wrote the Sa...