![]()

1

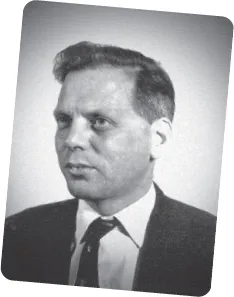

THE SCIENTIST: TOM KAISER

On a balmy afternoon in late July 1949, Sir Frederick Shedden—the permanent head of the Australian Department of Defence, chairman of the Defence Committee and member of the Council of Defence—met with his British counterparts at the Ministry of Defence in Storey’s Gate, London. A short distance away, in The Strand, another Australian, a postgraduate student of nuclear physics named Thomas Kaiser, was participating in a small and ineffectual political protest outside Australia House. Neither Kaiser nor Shedden was aware of the other, and the reasons for each being in London that afternoon were not related. Yet very soon the career of the young scientist would become entangled with the concerns of the powerful bureaucrat. Australia’s troubled defence relationship with the United States and Great Britain provides the backdrop for this unusual connection, but an analysis of the so-called ‘Kaiser case’ will reveal the profound personal impact of the Cold War on this individual.

At the height of the bitter 1949 general coal strike in Australia, a tiny group of young Australians living in London decided to demonstrate against the Chifley government’s strike-breaking actions.1 For four hours on a warm summer’s day, they handed out a thousand leaflets to passing Londoners. The demonstrators paraded placards reading ‘Eight T[rade] U[nion] leaders Gaoled! WHY?’ and ‘Dr Evatt: Democracy Begins at Home’, while the leaflet explained the ‘savage acts’ of the Australian Labor government in terms of imminent global conflict: ‘Why this attack? Because Australia occupies an important place in the plans of groups in America and Britain who are planning a new world war … The workers are opposed to these war preparations ...’2

Notwithstanding the widely held conviction that the Cold War in 1949 could soon turn hot and escalate into World War III, such an insignificant demonstration would normally have been ignored by the mainstream press. It was small in scale, none of the six young demonstrators was well known, there was no violence or obstruction, the police were not involved, and it was all over by five o’clock. The next day, 28 July 1949, only the Daily Worker, published by the Communist Party of Great Britain, carried a brief report accompanied by a photograph.

That this incident would soon make not only front-page news, but also lead to an official inquiry by the Australian High Commissioner, heated parliamentary exchanges, agitation in the offices of the Defence Department and Prime Minister’s Department, and a flurry of top secret cables at the highest levels between London, Canberra and Washington, was due to an MI5 informant learning that the identity of one of the Australians was Thomas Reeve Kaiser. Some called Kaiser a potential traitor, others a full-blown ‘atom bomb spy’. But not Sir David Rivett, the recently retired chairman of Kaiser’s employer, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). He was not troubled by Kaiser’s ‘exploits’, which would have been ignored ‘if only the local British had observed it, but apparently Canberra has not got the same sense of indifference to youthful folly’.3 He significantly underestimated the intensity of Canberra’s concern.

GENESIS OF THE KAISER CASE

Who was this young man? Born in Ivanhoe, Melbourne, to working-class parents in 1924, Tom was a ‘battler’ but highly gifted.4 He won both Victorian and Commonwealth government scholarships to attend the University of Melbourne where he gained his degrees—a bachelor of science and a master of science, receiving first-class honours and the Hamilton Radio Prize—in 1943 and 1946; by then his scholarly interests centred on radar and radiophysics. Kaiser’s rebellious tendency was evident early. In 1942 he was fined £1 for ‘indiscipline’ towards Professor Thomas Laby, the head of the Department of Natural Philosophy. In early 1944 he was appointed an assistant research officer with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Division of Radiophysics, in the field of Radio Counter Measures. The secretary to the CSIR executive was ‘particularly desirous’ of getting Kaiser since he was ‘the best student of his year’.5

The potential displayed by Kaiser at the University of Melbourne was also evident in Sydney, to which he moved in August 1946 to take up an appointment at the CSIR’s Radiophysics Laboratory. In view of subsequent concerns that Kaiser posed a risk to national security (a theme discussed further in Chapter 6), it is important to note that the relationship between radiophysics and missile research was close. In May 1946, the UK Department of Supply sent its senior military adviser, Lieutenant-General JF Evetts, to Australia to select a testing site for long-range rocket development. The connection between missile research, radar research, in which Kaiser was engaged during the war, and radiophysics, in which he was fast earning a reputation, is revealed in a top secret and highly significant memorandum:

It is apparent that the question of use of C.S.I.R. facilities, in particular of the Radio Physics Laboratory, is a matter of great importance which requires consideration on the highest possible level. Applied radar research … is central to the development of guided projectiles, and, if, as a result of the report of the British mission headed by Lt. Gen. Evetts, the United Kingdom and Australian governments decide that Australia should be used for the testing and development of these weapons, it appears certain that the facilities of the Radio Physics Laboratory will be required in addition to … qualified personnel.6

In this context opportunities, particularly for overseas training, seemed ripe for Kaiser. In the meantime, the accolades kept coming. One report commented that he ‘has continued to demonstrate his exceptional ability and … is an outstanding young man. He is one of those who should be kept in mind for early experience overseas’.7 The acting director of the Radiophysics Division was even more glowing in his assessment:

I have found Kaiser to have an excellent background of physics and of the fundamentals of radio techniques. He shows imagination and initiative together with an excellent command of both experimental and theoretical techniques. I consider that he has a very good chance of developing into a first-rate research physicist, one well up to the standard of 1851 Exhibition scholars for example.8

It was therefore consistent that in November 1946 Kaiser should be awarded a highly competitive and well-remunerated CSIR postgraduate research scholarship to study overseas in a chosen field. A place had to be found for him, so the Divisional Chief of Radiophysics, EG Bowen, recommended Kaiser to Lord Cherwell, one of Britain’s leading physicists. Once again, Kaiser received an unqualified recommendation: ‘I can commend [Kaiser] to you as a brilliant young man … I have little doubt that he will develop into a research physicist of first-rate ability’.9 When it became clear, in June 1947, that the redoubtable Lord Cherwell would find a place for Kaiser, that he would give Kaiser ‘senior standing in view of his M.Sc at Melbourne University’, and that he would act as supervisor of his DPhil on nuclear physics,10 a brilliant career in a burgeoning field seemed assured for this young working-class lad. By July, Kaiser was sailing to England.

It is perhaps only the retrospective wisdom afforded the historian that enables warning signals to be identified. It is likely that Kaiser, infected with more than a touch of idealism, even naiveté,11 would have ignored or dismissed such signs, had he known of them. When he applied for a passport on 12 May 1947, a copy was forwarded to the security service. The Director of the Commonwealth Investigation Service (CIS) recommended to the Department of Immigration that a passport not be issued.12 In this and other correspondence to the Attorney-General’s Department, the connections between communism, atomic research and the potential for espionage were explicitly drawn.

It has been reported that Kaiser was present at the Australian Association of Scientific Workers symposium on the [Woomera] rocket range … and there expressed himself as being against the project … Information received is to the effect that [Kaiser] holds strong Communist views and is alleged to have stated some time ago that it was his intention to proceed to Canada to obtain employment in connection with Atomic Energy experiments … It is reported that he recently lectured to members of the [Communist] Party in connection with the Atom Bomb controversy … This further instance of Communist affiliation [sic] within the C.S.I.R. establishment (considering, also, the proceedings of the Canadian Royal Commission; and additionally the L.R.W.P.) is a matter of increasing security concern … The aforesaid information is brought to your notice in view of his Communist views and his expressed intention of seeking work in the Atomic field.13

One does not have to read between too many lines to recognise the suspicion that Kaiser, if not an ‘embryo Fuchs’, was a potential Nunn May, a likely ‘fifth column overseas’.14 Since the sensational defection in September 1945 of a Russian cipher clerk, Igor Gouzenko, the spectre of Soviet spy rings hovered over atomic establishments. Due to Gouzenko’s revelations, the British nuclear physicist Dr Alan Nunn May was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1946. Gouzenko’s testimony also triggered a chain of events, one of which was the establishment by the Canadian government of a royal commission whose report was widely read by security services in the West.15 Another was the decision by MI5 to place Klaus Fuchs, one of Britain’s top three atomic scientists and a Soviet spy, under surveillance. His arrest, interrogation and confession ultimately led to the execution of the Rosenbergs in 1953. Nevertheless, Australian security’s assessment of Kaiser still fell well short of Vladimir Petrov’s cryptic but conspiratorial assessment of Kaiser’s movements: ‘Went on a mission to England’.16

Kaiser was saved by bureaucratic slowness: by the time the Acting Secretary of the Department of Immigration acted, on 1 August 1947,17 Kaiser had already left the country. But what remained on his security file, and this was retrieved two years later, were several pieces of ‘incriminating’ evidence: his membership of a pro-communist organisation, the Australian Association of Scientific Workers (AASW);18 a clipping from the communist Tribune, dated 22 February 1946, reporting that Kaiser admitted to the Kingsford branch of the Labor Party that he was a member of the Communist Party; his attendance at an AASW conference on ‘Atomic Power and the International Co-operation of Scientists’ in April 1946; his participation in a ‘special meeting’ of the AASW in June 1946 to protest against the sentence imposed upon Alan Nunn May; and his contribution to an AASW symposium in April 1947 on the Long Range Weapons Project (LRWP), at which Kaiser ‘revealed in conversation’ to the CIS informant—who was a scientist and a security plant inside the AASW—that he ‘recently addressed Warragamba Dam employees on the rocket range and the atom bomb’. The final item was a copy of a small advertisement in Tribune advertising a farewell party for Tom Kaiser on 11 July 1947.19

For the next two years at Oxford, from late August 1947 until mid 1949, Kaiser was immensely productive. He commenced work in late 1947 on his doctorate at the Clarendon Physics Laboratory at Oxford University under the supervision of Lord Cherwell. During the war, Cherwell (aka Frederick Lindemann) had been Churchill’s personal scientific adviser; in the late 1940s he collaborated with Klaus Fuchs on the separation of isotopes at Britain’s atomic research station at Harwell. In 1948, Kaiser’s sustained wor...