![]()

CHAPTER 1

How to Behave in Court

This chapter describes how people are expected to behave in court, and explains the basic rules about how self-represented people should conduct themselves. It explains where accused persons should stand or sit, how to address the judge and the court officials, and what the rules are for acceptable behaviour. It also contains advice on how a self-represented person can learn about court practices and procedures.

When people find themselves in court for the first time, they are often nervous, confused, frustrated, or scared. Some people present with extreme emotions, and are angry or volatile. Such rude behaviour tends to backfire, making the speaker less effective. One of the reasons for these emotions is people are worried about the rules they are expected to follow, and are frustrated at the fact they are in court. It is useful to remember that many persons in court feel the same way, and that the court officials, judges, prosecutors, court staff, and lawyers, are used to dealing with people who are worried about the system and their cases. For the most part, individuals who behave reasonably in court will not find themselves in trouble for making minor mistakes, such as addressing the judge with an incorrect title (such as “sir” instead of “Your Honour”).

1. Court Practices Vary

This chapter sets out some basic rules, but readers should be aware that the practices followed by individual courts vary. Different courts are organized differently. Where you are expected to stand, sit, and the title used to address the judge, lawyers, and prosecutor may be different in different cities or provinces. The easiest way to find out about local practices is to attend court and observe how court participants are addressing each other, where they stand, and how they behave. In addition, self-represented persons may ask the professionals how to behave. Information about this may be posted on provincial websites. Some basic principles are common across Canada, however.

2. Decorum: Politeness and Respect

No matter how frustrating an accused person finds the court process, it is important to maintain a proper decorum. Decorum refers to behaving politely and respectfully in court. This is true even when the accused believes the court process is unjust, because the accused believes that he or she is innocent.

Proper decorum occurs when the individuals involved listen when others speak, rather than interrupting. When an individual speaks, he or she should do so clearly and slowly enough for the judge and other people in court to make notes.

Proper decorum doesn’t mean giving up your case. People should present their cases strongly, but should do so politely but firmly. They should treat the other court participants with respect, even when they disagree. Sarcasm, rudeness, name calling, and shouting have no place in the justice system. People who behave badly may find themselves sanctioned by the court. Often, such sanctions are verbal, with a judge instructing the individual to behave properly. Generally, ignoring the rules of decorum will not help an individual present their case.

As an example, imagine that in an assault case, the witness is behaving politely and calmly, and the accused is shouting, rude, and condescending. Who do you think is more likely to have started the fight? Judges use the same common sense in answering this question that you do.

In extreme cases, if someone persists in rude or obstructive behaviour, such as shouting at a judge or swearing, the court might find the individual in contempt of court, which can result in a period of imprisonment. Contempt of court proceedings are rare, however. Court cases often deal with people who are in the grip of extreme emotions. Judges and lawyers understand that a person might be angry at being charged, or angry at hearing a witness tell a falsehood. Typically, an individual will not get in serious trouble for a momentary outburst or expression of emotion.

Individuals who endeavour to follow the basic rules of decorum — behaving politely and with respect — will typically find they will be treated this way in return.

3. How to Address the Justice or Judge

Anyone attending court will learn how to address the judge or justice quite quickly. Common terms are:

• For a justice of the peace: “Your Worship.”

• For a provincial or Superior Court judge: “Your Honour.”

• In some provinces, Superior Court judges may be referred to as “My Lord” or “My Lady.”

Other terms of respect such as “sir” or “ma’am” are also often acceptable.

4. How to Address Other Justice Officials

First names are not supposed to be used in court. Generally, the parties should refer to individuals using the honourifics Mr., Ms., or Madam, followed by their last name or title. With transgender or non-binary individuals, the court may inquire as to the proper mode of address. The theme underlying this is that there is a need to treat all individuals with respect.

Sometimes, when a person does not know the last name of the individual, they may refer to the parties by their role, for example:

• Madam Prosecutor (or Mr. Prosecutor)

• Mr. Reporter (or Madam Reporter)

• Madam Clerk (or Mr. Clerk)

5. To Whom to Direct Comments

In court, comments are expected to be directed to the judge. The participants are not supposed to speak to each other directly in court. In some courts, this practice may often be breached, with the parties speaking to each other directly. Some judges may humour this, but it may irritate others. Judges will speak up if a pattern of communication concerns them. The reason why comments are directed at the judge in court is to avoid the parties’ discussions degenerating into an argument.

In court, the judge is the only person who can make court orders binding the accused.

6. Listen and Don’t Interrupt

It is important to listen carefully to what the judge says. It is considered rude to interrupt the judge or an opposing party when they are speaking. If the prosecutor is speaking, the judge should give the accused an opportunity to speak as well. When the accused speaks, the prosecutor is expected to be silent to ensure the accused has a full opportunity to express himself or herself.

Sometimes, a court may forget to give a party the opportunity to speak. If this occurs, the accused should politely but firmly request the opportunity. For example, an accused whose right to speak has been overlooked might say:

Your Honour, I have not yet been given a chance to make submissions on this. Could I please do so now?

7. Observing

One excellent way to learn about the mechanics of the court process is to attend court and observe court proceedings. This can be done at in-person courts, and can also be done on the video courts. Video courts were once rare, but since the COVID-19 pandemic forced adjustments to proceedings, have become common in some jurisdictions. A few hours spent inside a courtroom, watching how lawyers interact with judges and court staff will teach the observer things such as —

• how to behave (and how not to behave),

• where to stand,

• when people are expected to stand and sit,

• how to address the judge, and

• how to address the parties.

In addition, observing in court will teach how to use the terminology common in court. Words such as “adjournment,” “arraignment,” “plea inquiry,” and more will become familiar. A glossary of commonly used terms is available on the downloadable forms kit which you can access through the link printed at the back of this book.

8. Asking Questions

Often, when an accused person’s matter is being addressed, he or she will be asked questions, and may not understand what is going on. If this occurs, it is important to speak up and ask questions. The judge will either explain what is happening, or will ask another person in court to meet with the accused to explain what is going on. If an individual doesn’t understand, he or she should not simply answer the questions. Here is a simple example of how to ask a question:

I’m sorry, Your Honour, I know I am being asked a question, but I really don’t know what is going on. Could someone please explain this to me?

9. Standing and Sitting

When a judge enters the courtroom, everyone is expected to stand. Typically, a court clerk or another official will state something such as, “All rise.” When the judge sits, the clerk will then open court, saying something like, “This honourable court is now in session, please be seated.” Everyone is expected to sit. A similar process is followed when court is closed.

Typically, people are expected to be seated in court, unless they are addressing (speaking to) the court. When lawyers are called upon to speak, they stand. A self-represented accused, when it is his or her turn to speak, will also be expected to stand. It is considered rude to address the court from a seated position, but often, courts will give individuals permission to sit when speaking. Someone who has a disability or mobility issue, will ordinarily be given permission to sit.

10. Where the Self-Represented Accused Is Expected to Stand or Sit in Court

Typically, there will be a place in the court where an accused person is expected to stand or sit. This may be in a prisoner’s box, at a table for the lawyers, or at another location in court. The court staff will usually direct an accused person where to stand if he or she does not know.

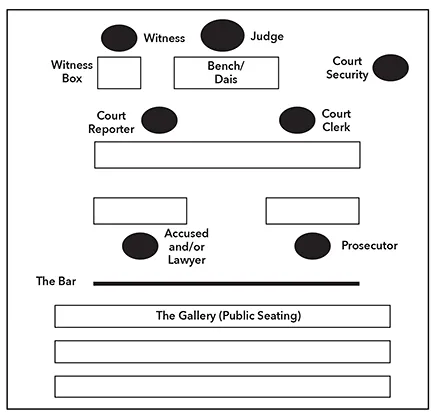

Figure 1 shows the layout of the court, and explains where the accused is expected to stand or sit in more detail. Not all courts are laid out in the same way, but most courts will have a number of similarities to the diagram, and include the following places:

Figure 1: Courtroom Diagram

• Judge’s dais or bench: This is the table where the judge sits.

• Court reporter’s and clerk’s bench: This is the table where the court reporter and clerk sit.

• Counsel tables: Th...