eBook - ePub

Classics from Papyrus to the Internet

An Introduction to Transmission and Reception

- 359 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Classics from Papyrus to the Internet

An Introduction to Transmission and Reception

About this book

A "valuable and useful" history of the efforts and innovations that have kept ancient literary classics alive through the centuries (

New England Classical Journal).

Writing down the epic tales of the Trojan War and the wanderings of Odysseus in texts that became the Iliad and the Odyssey was a defining moment in the intellectual history of the West, a moment from which many current conventions and attitudes toward books can be traced. But how did texts originally written on papyrus in perhaps the eighth century BC survive across nearly three millennia, so that today people can read them electronically on a smartphone?

Classics from Papyrus to the Internet provides a fresh, authoritative overview of the transmission and reception of classical texts from antiquity to the present. The authors begin with a discussion of ancient literacy, book production, papyrology, epigraphy, and scholarship, and then examine how classical texts were transmitted from the medieval period through the Renaissance and the Enlightenment to the modern era. They also address the question of reception, looking at how succeeding generations responded to classical texts, preserving some but not others. This sheds light on the origins of numerous scholarly disciplines that continue to shape our understanding of the past, as well as the determined effort required to keep the literary tradition alive. As a resource for students and scholars in fields such as classics, medieval studies, comparative literature, paleography, papyrology, and Egyptology, Classics from Papyrus to the Internet presents and discusses the major reference works and online professional tools for studying literary transmission.

Writing down the epic tales of the Trojan War and the wanderings of Odysseus in texts that became the Iliad and the Odyssey was a defining moment in the intellectual history of the West, a moment from which many current conventions and attitudes toward books can be traced. But how did texts originally written on papyrus in perhaps the eighth century BC survive across nearly three millennia, so that today people can read them electronically on a smartphone?

Classics from Papyrus to the Internet provides a fresh, authoritative overview of the transmission and reception of classical texts from antiquity to the present. The authors begin with a discussion of ancient literacy, book production, papyrology, epigraphy, and scholarship, and then examine how classical texts were transmitted from the medieval period through the Renaissance and the Enlightenment to the modern era. They also address the question of reception, looking at how succeeding generations responded to classical texts, preserving some but not others. This sheds light on the origins of numerous scholarly disciplines that continue to shape our understanding of the past, as well as the determined effort required to keep the literary tradition alive. As a resource for students and scholars in fields such as classics, medieval studies, comparative literature, paleography, papyrology, and Egyptology, Classics from Papyrus to the Internet presents and discusses the major reference works and online professional tools for studying literary transmission.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Classics from Papyrus to the Internet by Jeffrey M. Hunt,R. Alden Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Publishing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WRITING AND LITERATURE IN ANTIQUITY

THE OLDEST EXTANT WORKS OF GREEK LITERATURE, THE Homeric epics, famously begin in medias res. This expression most directly refers to the action of the plot, which for the Iliad begins near the end of the Trojan War and for the Odyssey at the end of Odysseus’ wanderings. Homer’s epics as literary works are also in medias res in the sense that they are a continuation of existing traditions and an incorporation of influences from Eastern literature. Yet they are often considered a beginning for Greek literature because of the remarkable, sustained cultural influence they held over ancient Greece and Rome. In fact, they are both. The Iliad and Odyssey could not exist without the established tale of the Trojan War and epic traditions of earlier cultures, but Homer’s work was not therefore an obligatory or replaceable part of the greater literary tradition.

Homer’s place in the literary tradition provides a fitting analogy for the development of Western thought, which was neither inevitable nor ex nihilo. On the contrary, prevailing currents of thought always stand in relation to the literature of the past, whether in emulation or rejection of preceding theories. It is often the case that old or ancient texts inspire fresh approaches to problems with which people have grappled for centuries, or even millennia (as recently as 1990, Derek Walcott penned his epic Omeros, a work whose name alone reveals its debt to Homer).

This text is primarily concerned with examining literary transmission in its broadest sense. Particular manuscripts will at times come into the discussion, though our focus will center largely on how attitudes toward texts develop over time, especially in reaction to changes in the physical form of the book. In so doing we will touch on a number of topics, including the origins of numerous scholarly disciplines that continue to shape our understanding of the past and the determined effort required to keep the literary tradition alive. We hope these analyses will collectively provide a window into current methods and attitudes toward texts, which, as at all points in time, are neither inevitable nor incontrovertible.

Our study of literary transmission must, like Homer’s epics, begin midstream, as it were, as we commence with an exploration of the origins and development of writing in ancient Greek and Roman societies. To do so efficiently, we shall pass over millennia of development that led to a watershed moment when the Greeks began to write, or at least to write what we commonly call ancient Greek. We do not bypass so much material arbitrarily; we do so only because the capacity to have produced the first written form of the Homeric epics represents a defining moment in the intellectual history of the West, a moment from which many current conventions and attitudes toward books can be traced. Thus, while we acknowledge that the Greeks and Romans, for all their originality, owe much to other cultures and themselves benefited from the transmission of ideas, we begin our discussion in medias res, starting with the slender but important evidence that we have for the development of books and writing.

Writing, which ultimately became a hallmark of Greek culture, made its way to Greece relatively late and to Rome even later. The alphabet was most likely introduced to Greece by Phoenician traders sometime around 800 BC. Greek writing predates the introduction of the alphabet, as evidenced by clay tablets found in the remains of Mycenaean palaces. These tablets are written in Linear B, a script derived from the older, but as yet indecipherable, Linear A, which was already in Crete by ca. 1700 BC.1 The Linear B tablets indicate the presence of a syllabary in use for Greek (primarily for record keeping) as far back as 1400, but its use seems to have been limited to the Mycenaeans themselves as no trace of it is found following the decline of that civilization around 1200.2

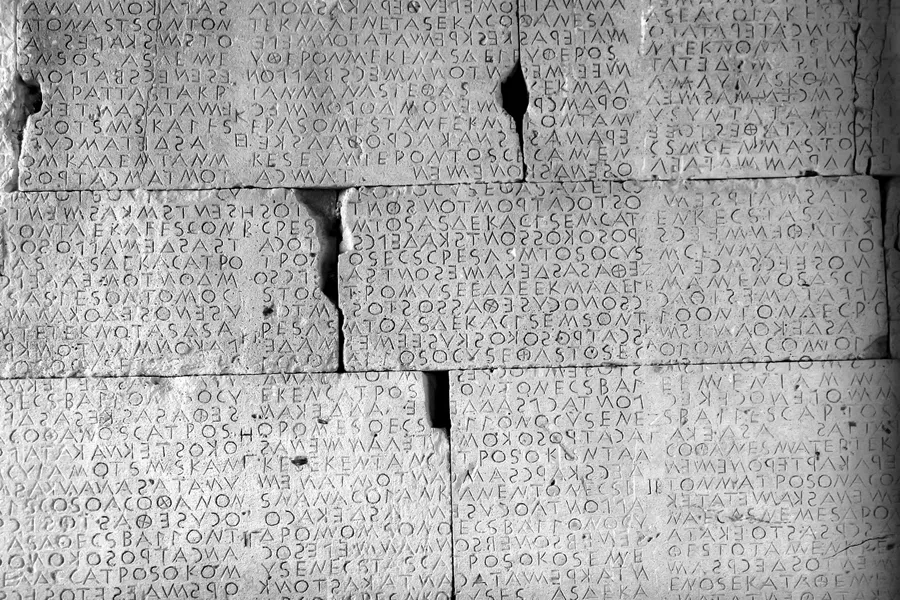

The transmission of the Phoenician alphabet to the Greeks is clear, for the names, forms, and order of the letters alpha through tau display remarkable similarity to corresponding Phoenician letters.3 Perhaps the most significant alteration made by the Greeks was to assign each letter to a single sound; many forms from the Phoenician system represented open syllables (i.e., a consonant sound paired with any vowel, thus allowing for multiple sounds from a single letter, the correct one to be determined in context). The Greeks represented vowel sounds with unique characters, a practice that was nascent in Phoenician writing but not yet developed. Also significant is the Greek tendency to use boustrophedon writing (see example in fig. 1.1) instead of the retrograde style characteristic of the Phoenicians.4 The bidirectional back-and-forth flow of text loosely mimics the motion followed by an ox plowing a field.

The transmission of the alphabet to the Greeks is placed by most scholars at about 800 BC, largely on the basis of the earliest appearance of Greek writing, which dates from the middle to late eighth century. Even at this early stage, however, the Greek alphabet demonstrates significant differences from its Semitic source, leading some scholars to posit an undocumented phase of transmission in the ninth century or earlier.5 The precise place of transmission is a more open question: Herodotus credits Cadmus with bringing the alphabet to Greece and identifies Boeotia as the point of transmission.6 Few scholars take Herodotus’ claim seriously, though Euboea, which is geographically close to Boeotia and was connected to it by trade, is a strong possibility, given the early date of inscriptions found both in Euboea and in colonies established by the Euboean cities of Chalcis and Eretria.7 Other sites of transmission have been proposed, however, including the Greek trading city of Al Mina,8 as well as Crete, Rhodes, and Cyprus, all of which are islands along the trade route to the East.9

FIGURE 1.1. Boustrophedon inscription from Apollonia. Sixth century BC.

That Greece acquired its alphabet from a single point of transition is largely agreed upon, despite the well-known diversity of numerous local (or “epichoric”) scripts. Throughout Greece, regional scripts show consistent variations from their Phoenician source, including the same shift of certain Phoenician consonants to Greek vowels—the division of the Phoenician wau U into the Greek digamma Ϝ (which took wau’s place as the sixth letter in the Greek alphabet) and upsilon Υ (which was placed after tau, the final Phoenician letter). Greek scripts also show a consistent confusion in their presentation of Phoenician sibilants that is otherwise inexplicable.10 The nearly ubiquitous Greek additions of phi Φ, chi Χ, and psi Ψ following upsilon Υ (although not always in the same order or with the same phonetic value) also suggest a single point of transmission.

Differences in the order of phi, chi, and psi and in their pronunciation help distinguish between broad categories of Greek scripts. The nineteenth-century scholar Adolf Kirchhoff assembled the various epichoric Greek scripts into a handful of categories and marked them on a color-coded map.11 The groupings are still often identified by the colors Kirchhoff used in his influential study. Eastern Greek scripts, including those of Attica, Corinth and her colonies, and Asia Minor are known as “blue” scripts, which display the familiar order and pronunciation phi [ph], chi [kh], psi [ps]. The western Greek “red” scripts, which occur throughout much of the Peloponnese, Boeotia, and Euboea and her colonies, instead preserve a different order and pronunciation: chi [ks], phi [ph], psi [kh]. It was from these western Greek “red” scripts that the Etruscans and other Italic peoples would acquire their alphabets, which in turn would influence the Latin alphabet used by the Romans. Kirchhoff identified a third—“green”—group of scripts used on the islands of Thera, Crete, and Melos, in which phi, chi, and psi do not appear. The cause of variation between red, blue, and green scripts is unknown, although the distribution of the scripts suggests they were spread along sea routes.

The diffusion of the Greeks’ recently formed alphabet must have happened rapidly, as Greek writing dating to 770 BC has been found as far inland on the Italic peninsula as Gabii.12 This diffusion, however, certainly does not imply a high rate or level of literacy. Of the relatively few inscriptions from the eighth and seventh centuries, most simply identify an object’s owner.13 However, it is noteworthy that evidence of literacy can sometimes defy expectations; for example, an Attic abecedarium (inscription of the alphabet) from before 500 BC found inscribed on a rock in pastureland suggests that even a shepherd could possess a rudimentary level of literacy.14

The oldest reference to writing in literature occurs in the Iliad. Book 6 contains an account of how Bellerophon, a victim of slander, is sent by King Proetus to deliver a message to the king of Lycia. Unbeknownst to Bellerophon, the tablet he carries instructs the Lycian king to kill him.15 Lines 168–16916 refer to a folded tablet (pinax ptuktos) engraved with marks that convey Proetus’ instructions (semata lugra, “woeful signs”). Clearly this passage demonstrates an awareness of tablets and writing, but its significance for Homer and ancient Greece has been debated. The passage seems to indicate that writing was normative in the eighth century,17 not only for brief dedications and household use but also for more substantial messages that facilitated long-distance communication between cities. Folding tablets, such as that in the Homeric passage, were nothing new in the Mediterranean world of the time, and this passage reveals that Homer was certainly aware of them. The degree to which writing was known and used in Greece, however, is debatable. Homer’s reference, for example, to semata (signs) instead of grammata (letters) may suggest that writing per se was not that widely diffused in eighth-century Greece.18

Inhabitants of Sicily and southern Italy soon encountered the Greeks’ alphabet, and, perhaps influenced by Greek colonists from Pithecusae, the Etruscans adapted it to fit their language. Epigraphic evidence for Etruscan writing dates to the seventh century. Unlike Greeks and Romans, the Etruscans did not distinguish between voiced consonants (sonants) and voiceless consonants (surds), and so had no need for the letters B, D, K, and Q.19 As a result, the Romans initially used C for both [k] and [g] sounds (presumably acquiring B, D, and Q from the Greeks or other Italic peoples, while K remained in use for a very few words). This practice can be easily seen in praenomina20 on inscriptions, which retained the archaic C where G would be expected. The letter G begins to appear around 269 BC (the change is often attributed to Appius Claudius Caecus, though Plutarch credits a certain Spurius Carvilius).21 It took the place of the Greek zeta, which was initially represented by the Latin S. The Greek digamma (Ϝ) became a Latin F. Already ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- 1. Writing and Literature in Antiquity

- 2. Grammar, Scholarship, and Scribal Practice from Antiquity to the Middle Ages

- 3. Classical Reception from Antiquity to the Middle Ages

- 4. Classics and Humanists

- 5. Classical Texts in the Age of Printing

- 6. Tools for the Modern Scholar

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index