- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Proportion and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art

About this book

This study of ancient Egyptian art reveals the evolution of aesthetic approaches to proportion and style through the ages.

The painted and relief-cut walls of ancient Egyptian tombs and temples record an amazing continuity of customs and beliefs over nearly 3,000 years. Even the artistic style of the scenes seems unchanging, but this appearance is deceptive. In this work, Gay Robins offers convincing evidence, based on a study of Egyptian usage of grid systems and proportions, that innovation and stylistic variation played a significant role in ancient Egyptian art.

Robins thoroughly explores the squared grid systems used by the ancient artists to proportion standing, sitting, and kneeling human figures. This investigation yields the first chronological account of proportional variations in male and female figures from the Early Dynastic to the Ptolemaic periods. Robins discusses the proportional changes underlying the revolutionary style instituted during the Amarna Period. She also considers how the grid system influenced the overall composition of scenes. Numerous line drawings with superimposed grids illustrate the text.

The painted and relief-cut walls of ancient Egyptian tombs and temples record an amazing continuity of customs and beliefs over nearly 3,000 years. Even the artistic style of the scenes seems unchanging, but this appearance is deceptive. In this work, Gay Robins offers convincing evidence, based on a study of Egyptian usage of grid systems and proportions, that innovation and stylistic variation played a significant role in ancient Egyptian art.

Robins thoroughly explores the squared grid systems used by the ancient artists to proportion standing, sitting, and kneeling human figures. This investigation yields the first chronological account of proportional variations in male and female figures from the Early Dynastic to the Ptolemaic periods. Robins discusses the proportional changes underlying the revolutionary style instituted during the Amarna Period. She also considers how the grid system influenced the overall composition of scenes. Numerous line drawings with superimposed grids illustrate the text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Proportion and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art by Gay Robins,Ann S. Fowler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Ancient Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Introduction

This book is a study of a fundamental aspect of ancient Egyptian art, namely, the use of squared grids made by the artists in drawing preliminary sketches of scenes and figures. I have undertaken it because although some features of the grid are already known, particularly in relation to individual seated and standing figures, others have been subject to misunderstanding, the treatment of kneeling figures has been neglected, and there has been virtually no consideration of how the grid relates to the composition of whole scenes or to different styles adopted at different periods.

Before turning to the grid itself, however, it is necessary to have an understanding of the general principles by which Egyptian draftsmen worked to produce what is arguably the finest artistic achievement of the Prehellenic world, which still holds a place among the best today. Nurtured by the unique civilization of the River Nile, the art of ancient Egypt gave expression to the thoughts and aspirations of an extraordinary people, chronicling their views of the world, the gods, society, life, and afterlife for over three thousand years. It is well known that the Egyptians raised great monuments to their deities and their dead, and the decoration of temples and tombs is a major source for our knowledge of Egyptian art, but art was not confined to religious and funerary contexts. Kings decorated their palaces and ordinary people their homes, and many household objects in everyday use were also ornamented. In fact, art played a part in every aspect of Egyptian civilization, in the worlds of the gods and their rituals, and in the life and death of mortals.

Modern viewers find much of Egyptian art familiar and readily understandable, so that they can appreciate it without knowledge of the aims and principles underlying its composition. But it also surprises them that these superb artists never “discovered” perspective. A closer look produces the even more startling revelation that the Egyptians seemingly did not know their right from their left; right hands appear on left arms and vice versa. Further, couples are often grouped together with different parts of their bodies overlapping in ways that just cannot happen in reality. Clearly Egyptian artists were either incredibly incompetent or they were not working according to the rules that many modern viewers expect.

In two-dimensional art, artists have the choice of accepting the drawing surface as flat, in which case they cannot directly reproduce an image of the world in three dimensions, or of finding ways to create the illusion of depth in their pictures. In the modern world, we are familiar with schematic systems such as plans of electric circuits, ground plans and elevations of buildings, and maps, all of which are purely two-dimensional on the flat drawing surface. These we are unlikely to count as art. It is the second choice, the creation of depth or perspective in a picture, that we expect to find in Western pictures, at least until the advent of “modern” art.

In perspective representation, artists adopt techniques to show the decrease in size of objects at a distance, the foreshortening of objects lying at an angle to the picture plane, and the convergence of parallel lines as they move away from the viewer. Already by 500 BC, the Greeks were experimenting with foreshortening and, soon after, with empirically making parallel lines converge. It was not until the Renaissance that what we can call Western or geometric perspective was brought into use, in order to provide a way of accurately reproducing architecture in two dimensions. The system was rooted in the scientific study of optics, of which the oldest surviving work, written about 300 BC, is by the Greek mathematician Euclid. Later Greek and Arab mathematicians in Egypt took his work further and their treatises became available in Europe in Latin translations by the thirteenth century AD. Western scholars continued to be interested in the study of optics; it was much in vogue in fifteenth-century Italy, and as a result scientific principles were used to formulate the rules of geometric perspective. The method is based on the use of a single static viewpoint for a complete composition together with a system of central convergence in which parallel lines meet at a vanishing point. This enables artists to capture scenes and postures from specific angles at a given moment of time. They can transfer what they see exactly onto the drawing surface, in much the same way that a camera transfers an image onto film.1

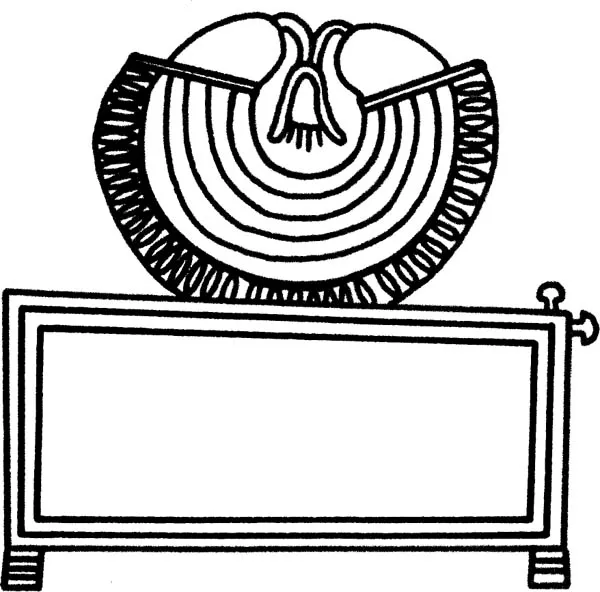

FIGURE 1.1

Representation of a box containing a necklace, TT 100, eighteenth dynasty, after Davies 1943, Plate 90.

This method was adopted in Europe at the time of the Renaissance and was used during the next four centuries virtually without a break until the midnineteenth century when new developments occurred, which interestingly were stimulated by the discovery of sophisticated artistic traditions in non-European cultures. Yet for many Western people, the eye still feels most comfortable with the geometric perspective employed in the bulk of their European artistic heritage. In fact, this type of perspective was a uniquely Western phenomenon. For instance, although the representation of space was fundamental to Chinese landscape art, artists had no scientific interest in perspective and its rules. The spaces involved were conveyed by a combination of a shifting viewpoint and a bird’s-eye view of the landscape, so that the eye is led over the painting and may, for example, be guided to follow a path up a mountain and then, on reaching the top, to look over at what is on the other side. Receding parallel lines in buildings are not generally shown as converging but as parallel, because this enables the eye to move more easily from one scene to the next.2

Similarly, Persian artists made no use of geometric perspective with its strict rules. Instead of one fixed viewpoint applying to all parts of the picture, they employed a system of multiple viewpoints, combining the resultant observations on one picture plane. Distance was usually indicated by placing items at different levels on the drawing surfaces, though without differentiation in scale.3

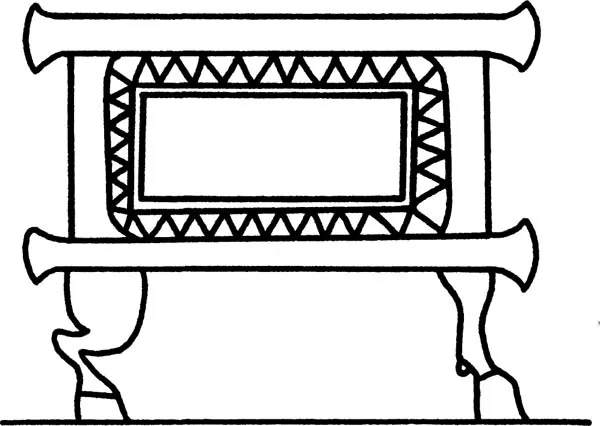

Western viewers must remember then that geometric perspective, which is so familiar, is not the only method of conveying the illusion of depth in a picture. But in ancient Egypt, artists did not even attempt to give depth as such to their compositions. They accepted the drawing surface as flat and represented the subjects of their composition through a series of symbols which they arranged over the surface. The aim of artists was to depict the enduring nature of the objects and scenes they portrayed; they were not interested in how these might appear at any one time from a particular viewpoint. They used established conventions to encode the information about the world that they wished to convey. Since viewers were familiar with these, they could easily grasp the meaning. A fundamental convention was that objects were shown in what was regarded as their most characteristic form, independent of time and space. They were usually represented by one of their surfaces, so a rectangular item like a box would be depicted by the side that gave the most immediately recognizable shape. If it was necessary to show the contents, these were drawn above the container (Fig. 1.1). If two or more surfaces of an object were considered important, they could be combined in one image; for instance, the legs of a stool could be shown in profile with the seat shown full view above them in the same plane (Fig. 1.2). These images were then arranged on the flat drawing surface to make up scenes.

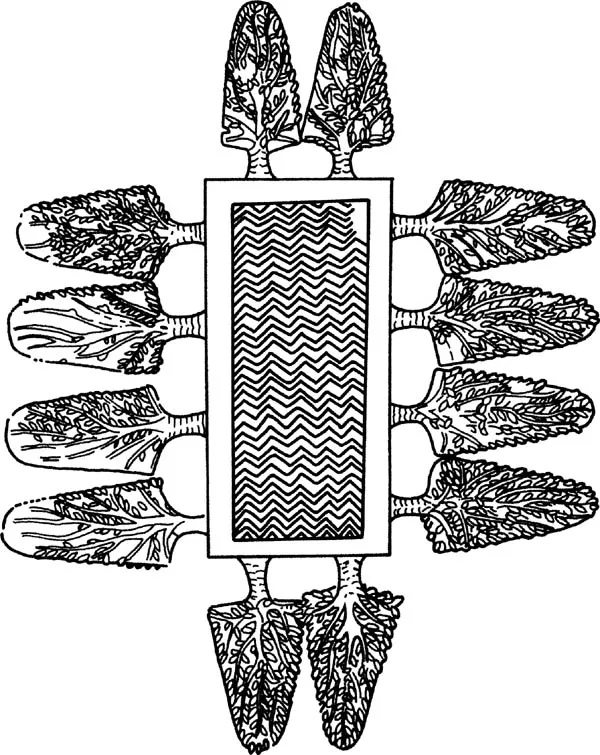

The schematic nature of Egyptian art is well illustrated by the way in which gardens were depicted. A typical Egyptian garden was laid out around a pool which was shown from above as a rectangle (Fig. 1.3). Within the rectangle, the artist could draw water plants, birds, fish, or boats. In real terms, some of these merely float on the surface of the pool, while others are actually in the water. Rows of trees standing around the pool to provide shade apparently lie flat on the ground. Nevertheless, the whole scheme provides a plan of a garden that can be readily understood and easily converted into real terms.

FIGURE 1.2

Representation of a stool, tomb chapel of Hesire, Saqqara, third dynasty, after Quibell 1913, Plate 18.

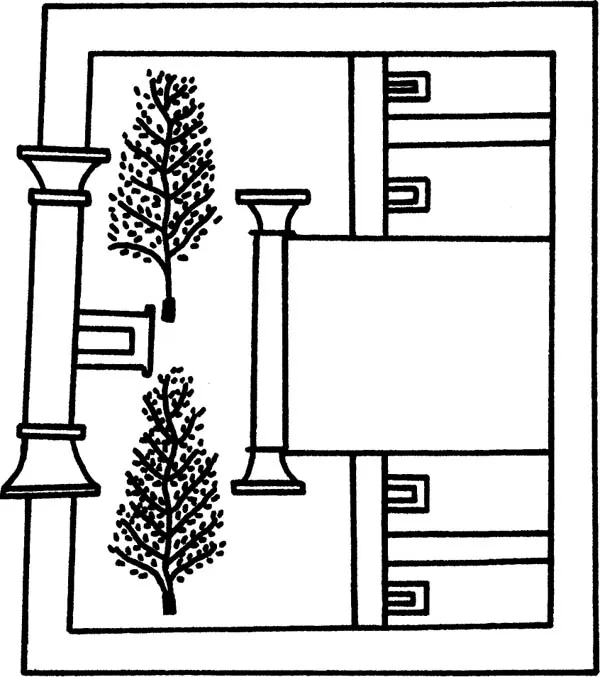

In the same way, architecture is sometimes represented by a plan of the building, within which individual elements like doors or pillars are shown in elevation (Fig. 1.4). Because these lie in the same drawing plane as the ground plan, they appear to be flat on the ground, just like the trees in relation to the pool.

These examples show that scenes in Egyptian art were built up from a variety of items, each represented on the drawing surface in its most characteristic form. It follows that artists were not reproducing directly from what they saw. Instead, they encoded what they wished to show by drawing on a stock of learned forms which they then assembled to make a scene.

FIGURE 1.3

Representation of a pool surrounded by trees, TT 100, eighteenth dynasty, after Davies 1943, Plate 79.

FIGURE 1.4

Representation of a building, TT 87, eighteenth dynasty, after author’s photograph.

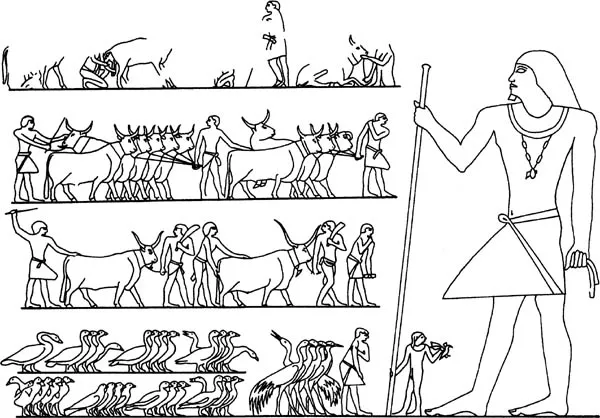

FIGURE 1.5

Scene, tomb chapel of Ptahhotep, Saqqara, fifth dynasty, after Davies 1900, Plate 21.

In order to organize this material on the drawing surface, artists divided the area into horizontal registers placed vertically above one another (Fig. 1.5). The surface itself was neutral in relation to time and space. Nor is there any indication of spatial or temporal relationship between the registers, although sets of registers were often given unity by setting a major figure at one end overlooking what was happening in them. The lower border of each register acted as the baseline for the figures within it. Sometimes part of a register was divided into subregisters which then provided baselines for smaller figures within the original register. Most commonly, the feet of all the figures in a register were placed on the baseline. This is tru...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Previous Work on the Grid and Proportions

- 3. Methods

- 4. Proportions in the Old and Middle Kingdoms

- 5. Proportions in the New Kingdom

- 6. Changes in the Amarna Period

- 7. The Late Period and After

- 8. Composition and the Grid

- 9. Nonhuman Elements and the Grid

- 10. Changing Proportions and Style

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index