![]()

PART II

TEXT

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Very many historians and researchers helped with information and connections with other people who knew something pertaining to the work in hand. All thanks to photographer Marty Stupich, whose idea of a book on the Red Desert started this project. Dr. Fred Lindzey, retired professor in Zoology and Physiology at the University of Wyoming, was the keystone connector to the naturalists at the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database at the University of Wyoming. Deputy Mary M. Hopkins at the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, and Steven Sutter, cultural resource specialist in the same organization, rooted out yellowed archeological reports that shed light on some of the mysteries of the Red Desert. The entire staff of the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center helped in many ways over the years in ferreting out rare manuscripts and ephemeral references related to Wyoming’s past. Leslie Shores, photo archivist, gave substance and place to the shadowed histories of early Wyoming ranch life. Assistant reference archivist Anne Guzzo provided a copy of the film Fight of the Wild Stallions, showing Red Desert horse-catching techniques in the 1940s. Trina Purcell of the Denver Public Library’s Western History and Genealogy department solved the riddle of the mysterious “CWA” cited often as a source in John Rolfe Burroughs’s Where the Old West Stayed Young. This turned out to refer to the Civil Works Administration, whose valuable 1930s interviews with residents of Colorado counties are housed in the Colorado Historical Society archives.

Dave Quitter of Saratoga spent many hours working to find references to Quien Hornet, the name of a mountain in the Red Desert that appeared on Howard Stansbury’s map. In the end, weeks of work resulted in a single footnote. He also helped with fine-tuning the geological photograph captions.

Dan Davidson, the director of the Museum of Northwest Colorado in Craig, pointed us to L. H. “Doc” Chivington’s useful manuscript, “Last Guard,” perhaps the best account of an ordinary cowpoke’s job at the turn of the last century in southwest Wyoming–northwest Colorado. Jan Gerber, the assistant director of this museum, provided photographs and information on bygone personalities of the Little Snake River valley, including W. W. “Wiff” Wilson, who bridged the era between cattle raising and oil extraction in Wyoming.

Cindy L. Brown, the reference archivist at the Wyoming Division of Cultural Resources, was helpful in tracking down references to the name change of “Washakie” to “Wamsutter.” Sandra Lowry, the librarian at the Fort Laramie National Historic Site, helped with day orders and documents showing that “Fort” La-Clede was not, in fact, part of the military fort system in Wyoming, but one of the Overland Stage stations fortified by Holladay.

Marva Felchlin, the director of the Autry Library at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, was very helpful with audio disks of lectures on American violence, especially in the west, and materials related to Wyoming outlaws and the diary of Second Lieutenant William Abbott, who served at Fort Fred Steele in 1872–1874.

Lindsay Ricketts made the first pass at copyediting and formatting a gnarly tangle of pages. Our rigorous editors at the University of Texas Press earned our profound gratitude for their punctilious work. Thank you, Megan Giller and freelancer Rosemary Wetherold.

Throughout the study period, the Western Wyoming Community College Oral History Project interviews with many people now gone helped us gain an intimate view of those who lived in and around the Red Desert. The useful bulletins and updates from concerned organizations included the Wyoming Outdoor Council, the Biodiversity Conservation Alliance, and Friends of the Red Desert. Bob Cook, outdoor liaison, map interpreter, and gifted selector of the best camping spots was indispensable on trips into the desert. Dudley Gardner was a spark plug; his terrible energy, unfailing optimism, and gritty determination, his knowledge of good coffee sources in southwest Wyoming and northwest Colorado, and his willingness to drive long, bad roads and sleep on the truck seat made him the ideal historian-archeologist for the project.

Pam Murdock and Mary Wilson of the BLM Rawlins Field Office guided us through the historically important JO ranch and were very helpful in supplying historical reports on the JO and Jawbone ranches. Thanks also to Oscar Simpson of the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division and the New Mexico Wildlife Federation for explanations of coal-bed methane gas extraction machinery and procedure.

Russel Tanner commented that rock art scholars “who deserve mention from the beginning for their contributions to the greater endeavor of scientific inventory, context development and description of various Native American rock art sites include David T. Vlcek, James Keyser, George Poetschat, Julie Francis, Alice Tratebus, Larry Loendorf, Linda Olson, Dudley Gardner, Bill Current, Tom Larson, Ron Dorn, Sam Drucker, and Joseph Bozovich Jr., and his esteemed father, the late Joe Bozovich Sr.” Russel Tanner also wishes to thank Clifford Duncan, Starr Weed, Floyd Osborn, Haman Wise, Delphine Clair, Burton Hutchinson, Henry Antelope, Bobby Joe Goggles, Sherry Blackburn, and Diana Mitchell, as well as the late Shorty Ferris, John Tarness, and Joe Pinnecouse.

George P. Jones thanks Fred Lindzey and Marty Stupich. Jeffrey Lockwood wrote that “his contribution to this book would not have been possible without the assistance of Scott Schell, Gary Beauvais, and George Jones.”

Charles Ferguson thanks Andrew Coen and Ron Surdam for discussions regarding limnology. Gerald Smith and Jon Spencer shared valuable unpublished information regarding fish evolution and the Colorado River. Richard W. Jones was very helpful with reference materials, as was the entire staff of the Brinkerhoff Geology Library at the University of Wyoming. Robert L. Cook was an invaluable field assistant. Annie Proulx, Steve Cather, and Michael Mahan reviewed earlier versions of the manuscript and improved it immensely.

Laura and Walter Fertig would like to thank Gary Beauvais, George Jones, Ron Hartman, and Bonnie Heidel for sharing thoughts and input on the ecology and botany of the Red Desert.

Andrea Orabona offers “sincere thanks to naturalists Mac Blewer, Marian Doane, and John Mionczynski for sharing their expertise and experiences with me while conducting additional research” for her chapter on birds of the Red Desert.

Dudley Gardner thanks Annie Proulx for “listening and editing” and writes that “Jana Pastor, David Johnson, Danny Walker, Mary Lou Larson, Michael Metcalf, Russel Tanner, Emma Gardner, Richard Etulain, Ken Fitschen, Barbara Smith, Murl Dirksen, Martin Lammers, Will Gardner, and Byron Loosle are owed my gratitude for commenting on the technical aspects of the sections on environment and prehistory.”

Craig Thompson states, “I regret the passive neglect suffered by my children, my wife, Jocelyn, and my students during my frenetic research and writing periods. I acknowledge the invaluable help of Dr. Ron Surdam, master detective and premier chronicler of Lake Gosiute, and Charles Matheson Love, the most observant fieldman with whom I have ever worked.”

![]()

INTRODUCTION

This book is not intended as another plea to save the greater Red Desert. Many tries for conservation by people who love the place have come and gone over the decades, defeated by the prevailing attitude of “show me the money,” by the congressional cold shoulder, by lack of knowledge of what is in that high desert, by the complex mixture of politics and culture, and by the momentum of our times, inexorably propelled by shifting global histories, which, like massive continental plates, have thrust us into the present.

This book tries to sort out what there is about the Red Desert that makes it valuable, scientifically and historically interesting. We hoped to dispel some of the myths that have grown up around the place.

There is nothing in the Red Desert but sagebrush, and who needs it?

Now that forage is depleted, the Red Desert is empty wasteland. Coal, oil, gas, gravel, and trona are its only assets.

There were never any ranches in the Red Desert.

Wildlife is mostly feral horses that eat grass that could otherwise nourish cattle and sheep.

There is no water.

The Red Desert had nothing to do with the formation of the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

The project began several years ago when photographer Martin Stupich asked me to write an introduction to a collection of his photographic work in the Red Desert. I agreed, thinking it would be a simple matter to go to the University of Wyoming’s library, gather up the books on the region, and write a general overview of the place. I was stunned to discover there was not one single book on the Red Desert in Coe Library. Nor did a search of the American Heritage Center’s archives turn up much beyond an old photograph of a locomotive stalled by the infamous 1949 blizzard, and a nineteenth-century paper on forage plants by the esteemed botanist Aven Nelson. What we did not know about this huge area of the state began to swell up into a thundercloud of general ignorance.

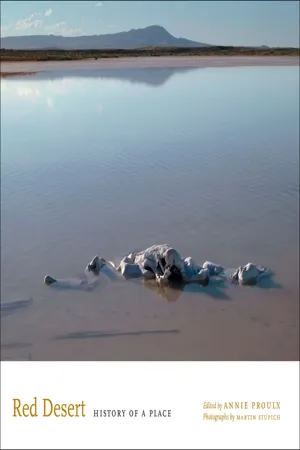

Martin Stupich’s photographs were not meant to illustrate the text, but are his stand-alone record of the desert over a period of years. The text grew up around what we didn’t know rather than the photographs. As we worked on the book, we learned that Red Desert fieldwork and study could absorb many lifetimes. Our book is only a start. Almost everyone who worked on the project came away excited by what they found, dazzled by the possibilities for learning more. Hydrologist Craig Thompson mentioned that Bitter Creek, draining one of the largest basins in North America, could enrich our knowledge of water in high desert.1 There are flowing wells out there that serve as oases for wildlife, ice lenses in the sand dunes that melt into pools of water. None of these are well studied. Prospector Bob Cook said that every trip revealed something new to him—barrel hoops, purple glass, selenium indicator plants, and “a zillion roads; it’s a spider web out there.”2 Entomologist Jeff Lockwood was amazed by the riches of insect life, which he said seemed “absolutely staggering,” adding that the diversity “has got to be phenomenal … the place is not homogeneous.”3 We learned that the Red is composed of rich pocket habitats catering to a wide variety of specialized vertebrates, invertebrates and plants, pockets that are scarcely known and certainly not mapped. Lockwood described these habitat pockets as archipelagos of life in the sea that is the Red Desert.

Cautions on Venturing into the Desert

ANNIE PROULX

The Red Desert is one of those places that easily humble and even humiliate those who think they know it. No one person knows this place. Many people know special small corners, feel at home on the flanks of certain mountains or inside the particular maze of rock outcrops or up on Green Mountain or the Haystacks looking south into the desert, but weather, rock-slides, reworked roads, and sidetracks can disorient even old hands.

Readers who are curious to see the Red Desert for themselves should be careful. If possible, do not go alone, and if you have never been there before, go with someone who knows the way. If you are alone and injure yourself, you may find yourself in a bad situation.

Some roads are thickly strewn with flinty rocks that can shred flimsy tires with ease. Flat tires are a common mishap in the Red. Ornithologist Andrea Orabona recalled what happened one year when, just after she had had knee surgery, she was doing her bird survey in the Red Desert: “On that trip, I was in my Game and Fish truck and got two flat tires on the way out of the Red Desert, but had only one spare. I always take my trekking poles, but also take my mountain bike—just in case—if there’s room. Since I was camping out of the back of my truck, there wasn’t room for the bike that time, so my only option was to walk out. I knew where the Sweetwater was.”1 Luck was with her. She met some lost tourists who had been looking for a grave site. They took her back to Lander, and she answered their many questions about wildlife and the desert. “It was a mutual rescue,” she said.

Geologist Charles Ferguson and prospector Bob Cook had a vehicle breakdown and faced a walk of a few miles to a larger gravel road that might have traffic on it. There was no traffic, and they waited and waited for many hours before someone—a Sweetwater County road grader—came along.

A rugged, four-wheel-drive vehicle with high clearance is a necessity on the old tracks, and heavy-duty tir...