eBook - ePub

The Cast Iron Forest

A Natural and Cultural History of the North American Cross Timbers

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Cast Iron Forest

A Natural and Cultural History of the North American Cross Timbers

About this book

"A thoughtful, thorough, and updated account of this bio-region" from the author of

From Sail to Steam: Four Centuries of Texas Maritime History, 1500-1900 (

Great Plains Research).

Winner, Friends of the Dallas Public Library Award, Texas Institute of Letters, 2001

A complex mosaic of post oak and blackjack oak forests interspersed with prairies, the Cross Timbers cover large portions of southeastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, and north central Texas. Home to indigenous peoples over several thousand years, the Cross Timbers were considered a barrier to westward expansion in the nineteenth century, until roads and railroads opened up the region to farmers, ranchers, coal miners, and modern city developers, all of whom changed its character in far-reaching ways.

This landmark book describes the natural environment of the Cross Timbers and interprets the role that people have played in transforming the region. Richard Francaviglia opens with a natural history that discusses the region's geography, geology, vegetation, and climate. He then traces the interaction of people and the landscape, from the earliest indigenous inhabitants and European explorers to the developers and residents of today's ever-expanding cities and suburbs. Many historical and contemporary maps and photographs illustrate the text.

"This is the most important, original, and comprehensive regional study yet to appear of the amazing Cross Timbers region in North America . . . It will likely be the standard benchmark survey of the region for quite some time." —John Miller Morris, Assistant Professor of Geography, University of Texas at San Antonio

Winner, Friends of the Dallas Public Library Award, Texas Institute of Letters, 2001

A complex mosaic of post oak and blackjack oak forests interspersed with prairies, the Cross Timbers cover large portions of southeastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, and north central Texas. Home to indigenous peoples over several thousand years, the Cross Timbers were considered a barrier to westward expansion in the nineteenth century, until roads and railroads opened up the region to farmers, ranchers, coal miners, and modern city developers, all of whom changed its character in far-reaching ways.

This landmark book describes the natural environment of the Cross Timbers and interprets the role that people have played in transforming the region. Richard Francaviglia opens with a natural history that discusses the region's geography, geology, vegetation, and climate. He then traces the interaction of people and the landscape, from the earliest indigenous inhabitants and European explorers to the developers and residents of today's ever-expanding cities and suburbs. Many historical and contemporary maps and photographs illustrate the text.

"This is the most important, original, and comprehensive regional study yet to appear of the amazing Cross Timbers region in North America . . . It will likely be the standard benchmark survey of the region for quite some time." —John Miller Morris, Assistant Professor of Geography, University of Texas at San Antonio

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cast Iron Forest by Richard V. Francaviglia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Natural History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

“The Natural Curiosities of the Country”

A BRIEF NATURAL HISTORY OF THE CROSS TIMBERS

The Cross Timber of Northern Texas, which may be deemed one of the natural curiosities of the country, forms a remarkable feature in its topography.

—WILLIAM KENNEDY, Texas: The Rise, Progress, and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, 1841

The Cross Timbers of the south central United States are a forested archipelago largely surrounded by a sea of prairie. Centered roughly between the 97th and 98th meridians, the Cross Timbers vegetation comprises generally north-south trending belts of scrubby oak trees. As suggested by William Kennedy’s use of the singular “Cross Timber,” the distinctive vegetation is distributed throughout the region in what, to many observers, appeared to be a single line. It was this distribution, as well as the character of the forested areas, that earned the Cross Timbers a reputation as a natural wonder in the nineteenth century. Even today, the Cross Timbers typically appears as dense stands of post oak and blackjack oak trees that rarely exceed about thirty feet in height, but that are visible for a considerable distance across the prairie (FIG. 1-1). In many places, the forest is dense and the crowns of the trees not only touch, but intermingle. The relatively even height of these oak trees makes clear the lay of the land beneath them, a land that is often gently rolling. In his classic description of the region, William Kennedy’s mention of “topography” in the same sentence as “Cross Timber” would prove prophetic, for geologists half a century later would confirm the intimate relationship between the forests of the Cross Timbers and the region’s geology.

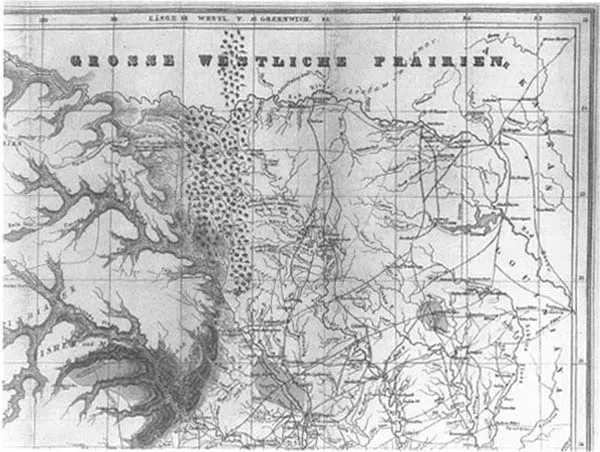

In the mid-nineteenth century, the term Cross Timber, or more often Cross Timbers, referred to a large area that consisted of a swath of trees stretching north of Waco along the Brazos River of Texas and extending far north into Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma. Like other naturalists of this era, Dr. Ferdinand Roemer was concerned not only with the character of the vegetation but also its distribution. His 1849 “Topographisch-geognostische Karte von Texas” (Topographic and Geological Map of Texas) illustrates the Cross Timbers by using stylized symbols for trees (FIG. 1-2). Roemer’s map is based on the 1845 “New and Correct Map of Texas” by T. D. Wilson, and it clearly shows the Cross Timbers occupying a large section of north central Texas and the adjacent Indian Territory across the Red River. In keeping with the Cross Timbers’ landmark status at that time, Roemer shows them running through the “Grosse Westliche Prairien” (Great Western Prairie). A careful study of Roemer’s map and its predecessors reveals the use of several symbols for trees in the Cross Timbers: in the map’s southern portion, Roemer depicts what appear to be oaks almost exclusively, while in the vicinity of the Trinity River and northward into Indian Territory, he also uses stylized pine tree symbols, which likely represent cedars. Roemer’s map therefore indicates that the Cross Timbers did not consist entirely of oak trees, but also other types of vegetation intermixed with the oaks.1

FIG. 1-1. As seen from the adjacent prairie, the Cross Timbers form a forested archipelago in a sea of grass. View near Marietta, Love County, Oklahoma (1997 photo by author).

In 1872, the well-traveled artist-writer Miner K. Kellogg traversed the prairie-forest region of the Indian Territory and Texas as part of the Texas Land and Copper Association expedition. With the eye of an artist, Kellogg observed that the traveler on the prairie beholds almost treeless country as far “as the eye can reach,” but that “in the misty distances appears a magnificent river winding through the grandest valley ever beheld.” Yet this, according to Kellogg, “is not a river—it is only the effect of the differences of color between the light green of the prairie grass and the darker lines of forests surrounding them.”2 Although the Cross Timbers appeared as a belt (or “river”) of forested land in some places, it was much less pronounced in many others. As Kellogg himself observed, “If we ever camped on picturesque spots I could exercise the [paint] brush—but all is monotony—Some green plains—& scrub oak parks alternately—[but] nothing to force a tired out man from reposing.”3 Kellogg’s description suggests that the Cross Timbers were less pronounced in some places than in others, but that the contrast between forest and prairie was nevertheless a visually defining aspect of the countryside.

Kellogg was not the first observer to traverse the Cross Timbers: natural historians and others had already been exploring there since the 1820s. By the time Roemer published his observations on Texas (1849), the Cross Timbers area of the state had become well known to naturalists seeking to explain the unique flora and fauna. With increases in knowledge, a clearer picture of the Cross Timbers’ vegetation pattern began to emerge. From naturalists’ writings this increasingly refined understanding of the Cross Timbers’ size and character becomes apparent. In 1855, the self-trained naturalist Dr. Gideon Lincecum wrote a letter to Dr. W. Spillman of Columbus, Mississippi, characterizing the region north of Marble Falls as

[T]he country that was originally called the cross timbers. This is a stripe of timber mostly post oak and cedar, lying nearly N.E. and S.W. and is in width from 30 to 40 miles. This has no lime, but abounds in Silex, Silecious clay, magnesia, iron, alum, some coal, various other minerals, and whole forrests [sic] in petrification.4

FIG. 1-2. Ferdinand Roemer’s topographic and geological map of Texas (1849) uses the name “Cross Tim[b]ers” as well as stylized tree symbols extending from Texas into the great Western prairie of Indian Territory (Courtesy Special Collections Division, The University of Texas at Arlington Libraries).

FIG. 1-3. A cross section of the geology on a traverse along the Texas and Pacific Railroad from east Texas to west-central Texas reveals the Cross Timbers’affinity for sedimentary sandstone rocks of varying geological ages. (Source Robert T. Hill, “The Topography and Geology of the Cross Timbers,” 1887; courtesy the Frank E. Lozo, Jr., Center for Cretaceous Stratigraphic Studies, The University of Texas at Arlington).

Lincecum noted that this area of central Texas is part of a topographically elevated area that is rough and broken, adding that its rises “are called mountains; well, they are little mountains, having the appearance of potato hills in the distance.”5 Lincecum’s comment that this area was “originally called the cross timbers” indicated that he recognized it as something different—similar to, but not truly part of, the actual Cross Timbers, which lay farther north. This landscape described by Lincecum as a “stripe of timber” was associated with sandstone substrate—a condition that characterized the Cross Timbers proper, but could be found in scattered locations elsewhere. The presence of those cedar trees, too, suggested that limestone lay nearby, and this fact was confirmed by Lincecum later in the description. Thus, naturalists determined the close relationship between the vegetation and the geology of this region by the mid-nineteenth century. They were responsible for giving a more careful (that is scientific) definition to the “Cross Timbers”—a term that had been widely used by the public for almost any oak-forested land in the mid-1800s.

It was the geologists, in fact, who would help delineate the Cross Timbers as a distinctive natural region. More than a century ago, Texas geologist Robert T. Hill noted, “The traveler, in crossing this region of Texas from east to west, along the line of the Texas and Pacific railroad, views the Cross Timbers merely as a grateful relief to the monotony of the prairies, and sees little in them worth remembering.” However, Hill went on to suggest that, to more careful observers, the Cross Timbers has “numerous points of interest bearing on their topographic and geologic relations.” To clarify, Hill drew a longitudinal transect (FIG. 1-3) along the Texas and Pacific railroad line, revealing the surprisingly close correlation among geology, topography, and vegetation.6 It was through detailed studies of the topography that a peculiarity of the Cross Timbers in Texas—the fact that they comprised two separate belts of forest separated by a large prairie—came to be understood. Because the eastern belt was on lower-lying land, it came to be called the Lower Cross Timbers, while the more elevated forest to the west was called the Upper Cross Timbers.

GEOLOGIC SECTION ALONG THE LINE OF THE TEXAS AND PACIFIC RAILWAY, FROM ELMO, KAUFMAN COUNTY, TO MILLSAP, PARKER COUNTY.

1. Terrel; 2. Dallas; 3. Eagle Ford; 4. Arlington; 5. Handley; 6. Fort Worth; 7. Ben Brook; 8. Weatherford; 9. Millsap.

A. Coast Plain—Marine Tertiary. B. Black Waxy Prairie—Riply and Rotten Limestone, of Gulf Series. C. Eagle Ford Shales, and accompanying prairies. D. Lower Cross Timbers—Timber Creek Group (“Dakota sandstone?” of Shumard). E. Grand Prairie Region—Comanche (Texas) Division of the Cretaceous. e′, e″, e3, Washita, or upper, division; e4, e5, e6, Lower, or Fredricksburg (Comanche Peak) division. F and G. Upper Cross Timbers—f′, f″, f3, Dinosaur Sands: g, g, Carboniferous Coal-measures. Faunal horizons—e8, Toxaater elegans Fauna; e″, Horizon of Gryphæa Pitcheri (var. Dilatata) with Ostrea carinata; e3, Gryphæa Pitcheri, var. Fornicula (Exogyra fornieulata; e4, Ammonites vespertinus; e5, Hippurites (Caprina) Limestone; e6, Comanche Peak Fauna, including horizon of Gryphæa Pitcheri with Ostrea Matheroniana.

In delineating the Texas Cross Timbers in such detail, Hill not only consulted the literature, but relied on extensive fieldwork that would have been difficult to conduct a generation earlier. Of the many scientists drawn to Texas before 1850, most—like the famed Roemer—explored far south of the Cross Timbers. Nevertheless, the Cross Timbers were so well known by that time that Roemer and other naturalists were often obligated to make at least passing reference to them in their overall discussions of the state’s natural history. Some reports included lengthy descriptions of the Cross Timbers based on the firsthand accounts of other observers who appeared to be trustworthy sources—but who related considerable hearsay. And yet, some very significant field research occurred in the Cross Timbers as naturalists were drawn there after the mid-nineteenth century. Among these multi-disciplinary scientists was Jacob Boll, the “Swiss naturalist and entomologist, whose collections in all fields of natural history in Texas are of the greatest importance.”7 Between 1860 and 1880, Boll explored the natural history of portions of north Texas in and adjacent to the Cross Timbers; although Boll’s work does not focus on interpreting the Cross Timbers per se, his fossil collecting helped scientists better understand the relationship of the Cross Timbers’ geology to that of the surrounding country.

Indeed, the maxim that a region’s geology is essential to understanding its ecology is borne out by the Cross Timbers. It was, in fact, the Cross Timbers’ geology that drew special attention from nineteenth-century scientists—perhaps because the entrepreneurs who supported such scrutiny were ever alert to mineral wealth in the form of ores and coal resources. An 1844 letter by Charles Elliot reveals the manner in which the Cross Timbers were eyed more than a century and a half ago not only for their vegetation but also for their potential to yield mineral resources. While traveling widely in the Texas Republic at that time, Elliot left a fairly detailed account of the Cross Timbers in a letter to his associate William Bollaert. Elliot wrote Bollaert that “the Cross Timbers running through the colony in a N.E. direction, is a section or belt of timber land of a loose yellow soil covered with an undergrowth of vines, sumach [sumac], redbud, and indications of productiveness, yet the land is not so lasting as the prairie.”8 Elliot then went on to note that “every variety of oak” as well as other trees could be found in the Cross Timbers. He added that “iron appears in the Cross Timbers in inexhaustible quantities” and also noted that deposits of “stone coal” could be found in large quantities near Bird’s Fort.9

Observers noted with much interest the relationship between iron-rich sediments and vegetation. In the Cross Timbers region, a dark brown siliceous iron ore was commonly found in the more elevated topography—the “low, wooded, erosion-resistant hills and isolated knobs known as ‘ironore knobs.’”10 This feature is part of the Woodbine Formation that lies just west of the Eagle Ford Shale. Deposited about 96 to 92 million years ago, the Woodbine Formation underlies the Eastern Cross Timbers. This forested strip of land lying between the Blackland Prairie to the east and the Grand Prairie to the west promised great mineral riches, notably iron and coal for industry. In retrospect, however, Elliot’s and many others’ assessment of iron in the Cross Timbers was exaggerated (though significant deposits do exist farther east in Texa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Frontispiece

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. “The Natural Curiosities of the Country”: A Brief Natural History of the Cross Timbers

- Chapter 2. “Through Forests of Cast Iron”: The European American Encounter with the Cross Timbers

- Chapter 3. “The Destroying Axe of the Pioneer”: The Transformation of the Cross Timbers

- Chapter 4. “Now We Have the Modern Cross Timbers”: The Persistence of a Perceptual Region

- Summary and Conclusion: “The Delightful Scenery We Have Traversed”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index