- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A colorful history of the island city on Texas's Gulf Coast and its survival through times of piracy, plague, civil war, and devastating natural disaster.

On the Gulf edge of Texas between land and sea stands Galveston Island. Shaped continually by wind and water, it is one of earth's ongoing creations, where time is forever new. Here, on the shoreline, embraced by the waves, a person can still feel the heartbeat of nature. And yet, for all the idyllic possibilities, Galveston's history has been anything but tranquil.

Across Galveston's sands have walked Indians, pirates, revolutionaries, the richest men of nineteenth-century Texas, soldiers, sailors, bootleggers, gamblers, prostitutes, physicians, entertainers, engineers, and preservationists. Major events in the island's past include hurricanes, yellow fever, smuggling, vice, the Civil War, the building of a medical school and port, raids by the Texas Rangers, and, always, the struggle to live in a precarious location.

Galveston: A History is an engrossing account that also explores the role of technology and the often contradictory relationship between technology and the city, providing a guide to both Galveston history and the dynamics of urban development.

On the Gulf edge of Texas between land and sea stands Galveston Island. Shaped continually by wind and water, it is one of earth's ongoing creations, where time is forever new. Here, on the shoreline, embraced by the waves, a person can still feel the heartbeat of nature. And yet, for all the idyllic possibilities, Galveston's history has been anything but tranquil.

Across Galveston's sands have walked Indians, pirates, revolutionaries, the richest men of nineteenth-century Texas, soldiers, sailors, bootleggers, gamblers, prostitutes, physicians, entertainers, engineers, and preservationists. Major events in the island's past include hurricanes, yellow fever, smuggling, vice, the Civil War, the building of a medical school and port, raids by the Texas Rangers, and, always, the struggle to live in a precarious location.

Galveston: A History is an engrossing account that also explores the role of technology and the often contradictory relationship between technology and the city, providing a guide to both Galveston history and the dynamics of urban development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Galveston by David G. McComb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE EDGE OF TIME

Chapter One

When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.

—John Muir, cited by John L. Tveten in Coastal Texas

—John Muir, cited by John L. Tveten in Coastal Texas

Galveston! The name resonates in the chords of imagination. There are others in our language: Virginia City, Jackson Hole, Aspen, Las Vegas, Key West, Dodge City, St. Augustine, Taos, Santa Fe. These are places we have heard about; places that are lodged in vague memory; places we will visit when we have the time. Because of their link with the past they all possess a romantic magnet. We are drawn to them by curiosity. So it is with Galveston. It is a name of imagery which summons four centuries of adventure, hope, tragedy, sin, and death.

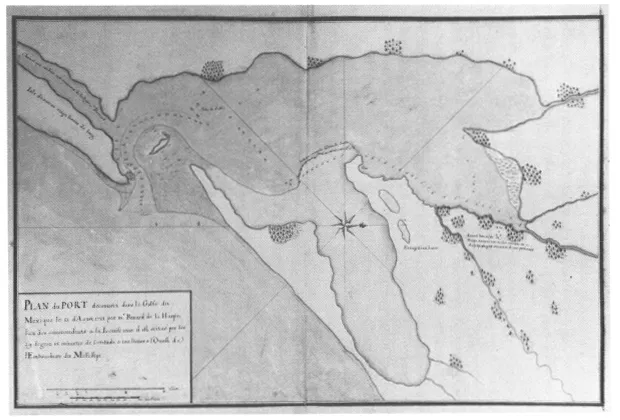

The Indian name for the island of Galveston was “Auia,” but in the sixteenth century the first Spaniards called it “Malhado,” the isle of doom.1 Sailing under the French flag, Bénard de La Harpe entered Galveston Bay in 1721, and attempted to establish a fort and trading post. The hostility of the local Indians prevented the success of his mission, but he included a map of the bay area in his account of the expedition. This is the earliest known map of Galveston Bay and its configurations are clearly revealed, even though La Harpe left Galveston Island unnamed and called the bay “Port François.” In 1785 José de Evia charted the Texas coast at the command of Count Bernardo de Gálvez, the viceroy of Mexico and the former Spanish governor of Louisiana. A tracing of his map at the Barker Texas History Center at the University of Texas at Austin shows the island labeled “Isla de San Luis” with the eastern tip called “Pt. de Culebras” (Snake Point). The bay to the north is labeled “Bd. de Galvestown.” A copy of the Evia map, printed in 1799, at the Rosenberg Library of Galveston, leaves Galveston Island unlabeled, notes Snake Point as “Pd. [sic] de Culebras,” and calls the area “Bahia de Galveztowm” [sic].2

Alexander von Humboldt in 1804 repeated the designations of “I. de S. Luis,” and “Pte de Culebras” for the island, and called the bay “Bahia de Galveston.” Stephen F. Austin also used this modern spelling of the name in his 1822 map of the coastline. He labeled the island “San Luis,” noted the Bolivar Peninsula, which was named for the great South American liberator, and drew a series of small houses on the eastern end of the island as “Galveston.” The David H. Burr map, “Texas,” in 1833 changed the name of the island to “Galveston Island,” and included Pelican Island.3 The Galveston City Company which established the city in 1838 used the name “Galveston” and thus firmly anchored the name in time.4

The island is located on the northwest coast of the Gulf of Mexico, fifty miles southeast of Houston, Texas. It is 345 miles west of the Mississippi River and 280 miles from the Rio Grande, at 29°18′17″ latitude and 94°46′30″ longitude. It varies in width from one and one-half miles to three miles, and is twenty-seven miles long.5 Lying parallel to the coast two miles away, Galveston stands as a guardian protecting the land and the bay from the Gulf. The long straight edge facing the sea, which was cut by several short bayous in early days, offers a smooth, sandy beach, while the side facing the mainland is serrated into salt marshes and tidal flats except where altered by humans.

To a geologist Galveston is a sand barrier island. Such islands line and protect the Texas coast. Sand and silt carried by currents from as far away as the Mississippi River move parallel to the shore. As waves reach shallow water and form breakers, they lose their capacity to carry a load. They dump the sand, and eventually an island forms. Sea level changes and catastrophic events, like hurricanes, also play a role. Storms pick up shells and rocks from as deep as eighty feet and deposit them on land. They submerge mud flats with new layers and rearrange shore lines. The 1900 hurricane, for instance, pushed the beach back several hundred feet. The northeast tip of the island has moved westward, and there is evidence from the exposed clay deposits on the Gulf side that the island is moving closer to land.

Pelican Island, the small isle to the north of Galveston, was a narrow marsh with only a hundred feet of dry soil in 1816. Pelican Spit, now a part of Pelican Island, was a tidal marsh and shoal as late as 1841. The spit and the island were silt catchers, and prime roosting grounds for seabirds. They gradually enlarged, joined, and emerged above the sea in the nineteenth century.6

Galveston Island essentially consists of gray, brownish-gray, and pale yellow fine sand to a depth of many feet. While drilling for water in 1891, the workers took soil samples every 5 feet. To a depth of 1,500 feet the drill went through various layers of sand, clay, shell, sandstone, and shell conglomerates. From as deep as 900 feet the drill brought up fragments of wood. There was no underlying bedrock; it was truly an island of sand.7 The water table lies within 4 feet of the surface and is brackish. Salt permeates the soil, and to the surprise of the new householders of the Lindale subdivision of the 1950’s, their underground water pipes corroded to dust and had to be replaced.8 Galvestonians, thus, have to import both water and topsoil.

MAP 1. Galveston Bay. Map made by Bénard de La Harpe, 1721. Courtesy of the Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas.

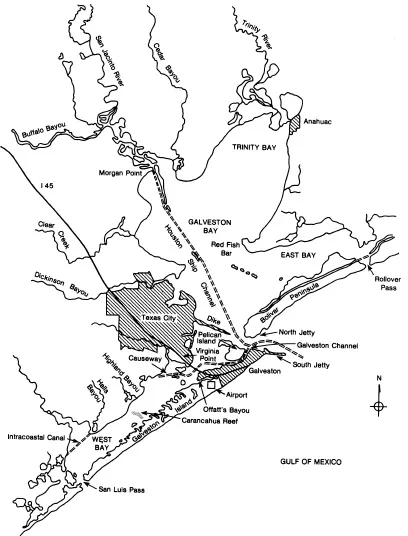

The side of the island toward Galveston Bay consists of mud flats except where “improved” by human beings. Between Galveston and nearby Pelican Island is the Galveston channel, which was scooped out by a bay current. It formed a natural harbor for the sailing vessels and small steamers of the nineteenth century. It attracted early exploitation and was the major geographical feature which made the place desirable. An inner sandbar formed across the channel near its exit into the bay on the northeast end after 1843, and an outer bar, always there, obstructed the entrance from the Gulf into Galveston Bay. The outer bar stretched in horseshoe configuration with the arch pointed toward the sea for four miles between the eastern tip of Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula.9 Still, this was the best natural port between New Orleans and Vera Cruz. “Galveston will be the sea Port sir, for this province,” wrote a Texas pioneer in 1822, “water plenty, good Harbour, also an ancorage are exceled by non . . . ”10

Extending to the north for thirty miles lies Galveston Bay. It is irregular in shape, about seventeen miles wide and generally seven to eight feet deep. It is the drainage basin for numerous small creeks and rivers. Dickinson Bayou, Clear Creek, and Buffalo Bayou are on the west; the San Jacinto River, Cedar Bayou, and the Trinity River are on the north. A large portion of the northeast quadrant is taken as the estuary of the Trinity River and forms Trinity Bay. South of that is East Bay, which Bolivar Peninsula separates from the sea. In the southwest quadrant is West Bay, which is formed by the two-mile expanse of water between Galveston Island and the mainland of Galveston County. Several small streams, including Halls Bayou and Highland Bayou, feed this portion. The gap between Galveston Island and Bolivar represents the main entryway into the bay, although there is an exit on the west end of Galveston Island called San Luis Pass. There was once an attempt to set up a rival town at that point, but the water was too shallow. The pass serves mainly as a tidal funnel for West Bay.

MAP 2. The Galveston Bay Area

The geological formation is relatively recent. The Gulf of Mexico appeared in the middle Mesozoic Era, about 180 million years ago. The sea advanced and retreated over the region at least nine times and left sedimentary deposits. The vast layers of sand and gravel put down at this time and later in the Cenozoic Era provided the basis for the artesian water and oil resources used in the twentieth century. Around Houston the deposits are twenty thousand feet thick. The youngest stratum is near the coast, and in the spoilage from the dredges at the Texas City dike are found the fossilized teeth and bones of ancient camels and horses. Throughout the area huge plugs of rock salt have punched through the sedimentary strata from salt beds far below. The bent edges of the rock layers caused folds and faults which trapped natural gas and petroleum. The domes also gave sulphur, salt, and gypsum.11 What happened over 100 million years ago provided an environment of natural resources—salt, oil, gas, sulphur, water, rivers, and harbors—which combined in the twentieth century with the technology and ambition of human beings to establish a petrochemical industry that dominates the economic life of the region.

The land of the Gulf coastal plain slopes gently about two feet every mile. It is only forty feet above sea level in northwest Galveston County. The gradual descent continues into the water and then drops somewhat more rapidly to the edge of the continental shelf six miles from shore.12 The soil on the mainland of Galveston County does not drain well. There are heavy clay subsoils which remain saturated with moisture for long periods. Portions, moreover, have high salt content, and the native vegetation is coarse grass and herbaceous plants. As a result, farming has never been particularly successful. Even as late as 1930, only 17 percent of the land was used for farming.13

An example of the difficulty with the land occurred in 1940–1941 when the federal government built an Army base near Highland Bayou. Camp Wallace had the advantages of proximity to the established base of Fort Crockett at Galveston, an urban water supply, and access to electricity. It possessed 1,600 acres, 161 barracks, a payroll of $150,000 per week, almost four hundred buildings, and a capacity for twelve thousand men. The disadvantages were weather and soil conditions which translated into drainage and flood-control problems. During construction the site flooded three feet deep after a nine-inch rainfall in November 1940. Roads washed away and the only way to move was with horses. There was brief consideration of a shift to higher ground, but the engineers persisted because of high land prices elsewhere. They emphasized the construction of ditches and the building of a railroad. Rail lines, historically, were the way to beat the mud of the area.

The engineers used draglines to dig ditches around the site and laid down three layers of planks to build a road. In December a six-inch rain flooded the site again. Draglines bogged in the mud and the plank road floated away. Soldiers worked knee deep at “Lake Wallace” to unload lumber from a spur track and to watch the material to be certain it did not drift away. The soldiers had to widen the bayou and place ditches throughout the campsite. Eventually they built shell roads with materials dredged from Galveston Bay. Even then roads had to be maintained by hand to remove the large clumps of waxy clay mud that dropped off the tires of trucks. Success came in May 1941, when a six-inch rain left only mud and no flooding.

Late in 1943 the Army left the site. The Navy took it over for a year as a boot camp, but after the war gave it up entirely. The government eventually divided it among Galveston County, the University of Houston, and the Hitchcock School District.14 The story of Camp Wallace underscores the problems of land use in the coastal area. This environmental limitation also explains part of the success of Houston in the nineteenth century. In contrast to Galveston, Houston possessed a hinterland which produced cotton and other agricultural products. The surrounding land provided an agricultural base for a growing city. True, there was mud to overcome, but Houston merchants solved that with the widespread use of railroads.15 Galveston lacked nearby farmland and had to span two miles of water and a county before reaching productive soil like that which encircled Houston.

The mud flats and salt marshes which rimmed the bay and the northern part of Galveston Island, nonetheless, are extraordinary. An acre of marsh produces ten times more protein than an acre of farmland. Cordgrass, sedges, and rushes with their roots in brackish water shelter, for example, frogs, spiders, snakes, bees, butterflies, herons, bitterns, blackbirds, mice, and ducks. Ninety percent of the coastal fish and shellfish depend upon the estuaries.16 The marsh is intensely alive. A Rice University report on the wetlands of East Bay states:

The plants, predominantly grasses, that flourish in this environment serve two biological functions: productivity and protection. From the amount of reduced carbon fixed by these plants during photosynthesis, this ecotone must be considered one of the most productive areas in the world and truly the pantry of the oceans. The dense stand of grass also represents a jungle of roots, stems, and leaves in which the organisms of the marsh, the “peelers,” larvae, fry, “bobs,” and fingerlings seek refuge from predators. Organisms invade from both fronts, fresh and saline. Insects, spiders, birds, and mammals from the landward face. Crabs, clams, oysters, shrimp, and fish from the marine environment. The energy of the sun is trapped in the process of photosynthesis. Herbivors, the primary consumers devour these plants, and they in turn are eaten by other predators in the food chain.17

Alligators are common in the mainland marshes and show up once in a while on the island. In 1875 citizens observed a four-foot alligator comfortably walking along the street near Postoffice and 25th. In 1877 a seven-foot reptile was caught near the wharves, and in 1948 workers near John Sealy Hospital found a ten-foot beast in a drainpipe. In 1958 fishermen roped a 275-pound one in shallow water near the jetty on East Beach and towed it ashore. In East Bay in 1961 after Hurricane Carla men shot a twelve-foot, 400-pound alligator which had probably been dislodged by the storm.18

Much more common to Galveston and of greater danger are the rattlesnakes. The Indians feared them and avoided permanent settlement in part because of them. The early maps designate the eastern tip as the “Point of the Snakes.” Every year, even now, doctors at the University of Texas Medical Branch treat twenty to thirty people for snakebite. These reptiles stay mainly in the marshes and the sand dunes of the west end, but sometimes show up in town. In 1964, for example, Willie Burns, the police chief at the time, was resting at home while his wife was working in the garden. He heard her scream, “Willie, it’s a rattlesnake! Don’t move! Call the police!” There was a five-foot ratt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1. The Edge of Time

- 2. The New York of Texas

- 3. The Oleander City

- 4. The Great Storm and the Technological Response

- 5. The Free State of Galveston

- 6. Galveston Island: Its Time Has Come . . . Again

- Notes

- Index