- 521 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

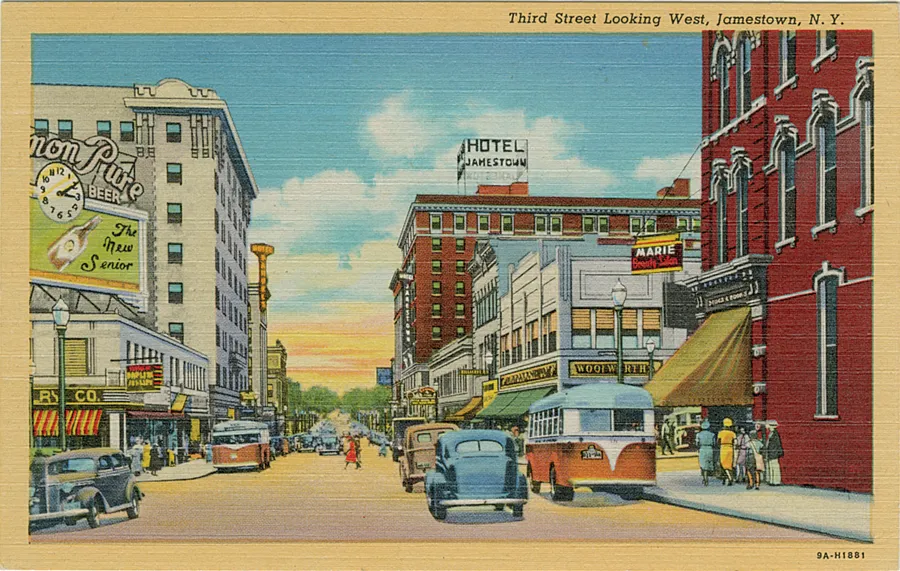

About this book

This illustrated history of the colorized linen postcards of the 1930s and '40s is "

an incredible tour . . . A veritable treasure trove of American culture" (

Crave Online).

From the Great Depression through the early postwar years, any postcard sent in America was more than likely a "linen" card. Colorized in vivid, often exaggerated hues and printed on card stock embossed with a linen-like texture, linen postcards celebrated the American scene with views of majestic landscapes, modern cityscapes, roadside attractions, and other notable features. These colorful images portrayed the United States as shimmering with promise, quite unlike the black-and-white worlds of documentary photography or Life magazine.

Linen postcards were enormously popular, with close to a billion printed and sold. Postcard America offers the first comprehensive study of these cards and their cultural significance. Drawing on the production files of Curt Teich & Co. of Chicago, the originator of linen postcards, Jeffrey L. Meikle reveals how photographic views were transformed into colorized postcard images—often by means of manipulation—adding and deleting details or collaging bits and pieces from several photos. He presents two extensive portfolios of postcards—landscapes and cityscapes—that comprise a representative iconography of linen postcard views. For each image, Meikle explains the postcard's subject, describes aspects of its production, and places it in social and cultural contexts. In the concluding chapter, he shifts from historical interpretation to a contemporary viewpoint, considering nostalgia as a motive for collectors and others who are fascinated today by these striking images.

From the Great Depression through the early postwar years, any postcard sent in America was more than likely a "linen" card. Colorized in vivid, often exaggerated hues and printed on card stock embossed with a linen-like texture, linen postcards celebrated the American scene with views of majestic landscapes, modern cityscapes, roadside attractions, and other notable features. These colorful images portrayed the United States as shimmering with promise, quite unlike the black-and-white worlds of documentary photography or Life magazine.

Linen postcards were enormously popular, with close to a billion printed and sold. Postcard America offers the first comprehensive study of these cards and their cultural significance. Drawing on the production files of Curt Teich & Co. of Chicago, the originator of linen postcards, Jeffrey L. Meikle reveals how photographic views were transformed into colorized postcard images—often by means of manipulation—adding and deleting details or collaging bits and pieces from several photos. He presents two extensive portfolios of postcards—landscapes and cityscapes—that comprise a representative iconography of linen postcard views. For each image, Meikle explains the postcard's subject, describes aspects of its production, and places it in social and cultural contexts. In the concluding chapter, he shifts from historical interpretation to a contemporary viewpoint, considering nostalgia as a motive for collectors and others who are fascinated today by these striking images.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Postcard America by Jeffrey L. Meikle in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781477308608Subtopic

Histoire de la photographie1

“They Do Say It’s Real”

AN INTRODUCTION TO LINEN POSTCARDS

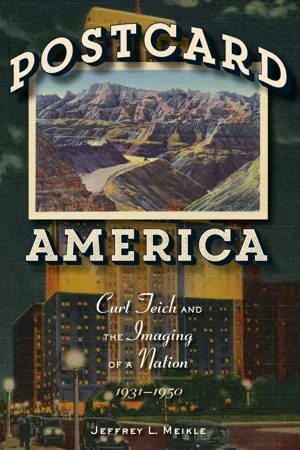

EARLY IN MARCH 1937 A WOMAN IN WESTERN New York received a colorful postcard offering a vivid contrast to the gloom of late winter (fig. 1.1). Sent from Tucson, Arizona, the card illustrates a radiant desert landscape in nearby Sahuaro National Monument. Several majestic saguaro cactuses stand tall against a sky artfully streaked with reds, yellows, and purples. Long shadows, anticipating a gorgeous sunset, cross a dirt road curving toward a distant horizon of purple mountains. Although the recipient’s reaction to the card is unknown, the sender conveyed something of her state of mind in the fragmentary style of most such messages. “How come I haven’t heard from you,” she asked, “do I owe you a letter (as usual)?” Her question demonstrates a basic function of postcards, reminding friends or relatives that one is thinking of them without having to say anything more. She also offered evidence of a common problem with popular forms of visual representation. “Haven’t seen this,” she admitted, referring to the card’s desert scene, “but they do say it’s real.”1

FIG. 1.1. “Sahuaro National Monument, near Tucson, Arizona,” Teich 6A-H715, 1936

Her expression of doubt may merely indicate a belief that “seeing is believing.” From our perspective, however, the postcard’s image, composed of bold dark lines contrasting with delicate color washes, falls midway between the apparent realism of a color photograph and the imaginative license of a watercolor or pastel. An examination of the card’s surface reveals an embossed pattern of delicate parallel lines running horizontally and vertically, some more prominent than others, suggesting the weave of an artist’s canvas, on which the image is printed. Seen through twenty-first-century eyes, this image represents the general idea of a desert landscape but hardly seems a photographic slice of a particular moment of reality. Even so, this postcard and thousands of others comprise a popular full-color portrayal of the United States during an era often later envisioned as existing in monotone black-and-white. If these cards seem now to fall short of realism, they must have been accepted in their own time as at least approximating reality.

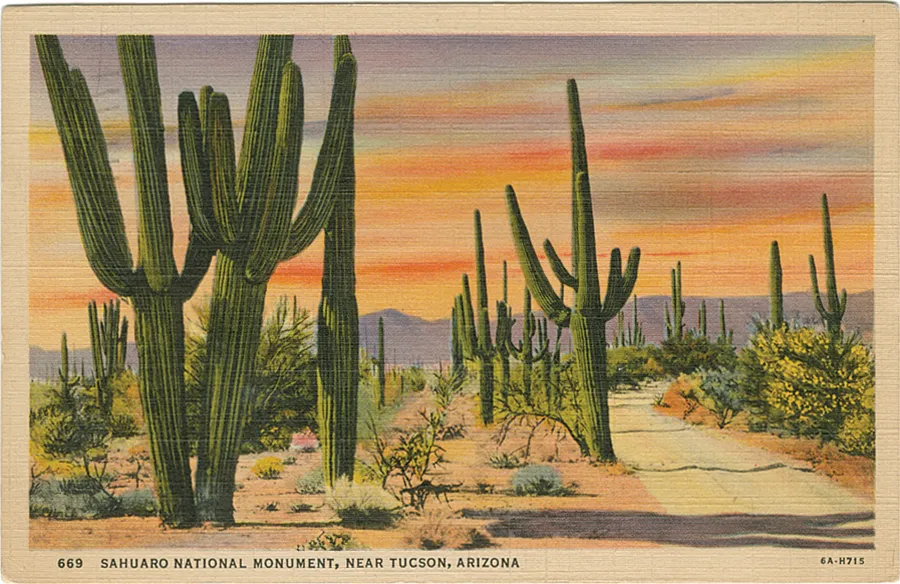

Linen postcards, so called for their embossed surfaces resembling linen cloth, dominated the American market for landscape view cards from 1931 into the early 1950s. By then, competing cards known as “chromes,” with shiny surfaces based on Kodachrome color transparencies, were in the process of replacing them. The linen variety, so unlike any other postcards before or since, was originated by Curt Teich & Co. of Chicago and widely imitated by other printers. Based on retouched black-and-white photographs, linen cards were printed by offset lithography on inexpensive card stock in vivid, exaggerated colors. Teich’s sales booklets celebrated the “striking note of smartness” of the “linenized effect” and praised these “beautiful miniature paintings” as the most “aristocratic of all post cards.”2 In fact, however, they were printed by the millions, were often sold for just a penny, and were sometimes given away by businesses as promotional items. Linen postcards offered a unique, recognizable vision of America. Whether representing natural landscapes, roadside attractions, or marvels of modern technology, the miniature images of linen view cards, about 3-1/2 by 5-1/2 inches in size, portrayed the American scene as shimmering with promise during the uncertain times of the Great Depression and World War II (fig. 1.2). Their saturated colors provided a popular view of the United States not displayed in grainy newspaper photos, high-contrast Life magazine photos, or the stark documentary work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans.

FIG. 1.2. “Delaware River Bridge Connecting Philadelphia, Pa. and Camden, N.J.,” Teich 3A-H963, 1933

These colorful postcards remained submerged for decades, hidden away in neglected albums and shoeboxes. Only recently has this alternative vision risen into popular and historical consciousness. Some linen cards have entered museum collections or historical archives after the deaths of original purchasers or recipients. Descendants have inherited and kept others. Most cards that survived natural attrition by now have passed to dealers and collectors through estate sales and auctions. Although postcard collectors have existed since the early 1900s, linen cards have attained status as true collectibles only recently as their era receded into history and their style acquired a desirable retro quality. As for historians, while some have reproduced linen postcards as illustrations in books devoted to other topics, no one has yet fully examined their significance as cultural artifacts. My interpretation of linen postcards involves a dual approach, considering primarily their meanings for the people who initially purchased, sent, received, or saved them, and secondarily their quite different meanings for people who later collected or drew inspiration from them. For a cultural historian, the encyclopedic iconography of these view cards offers a window onto popular middle-class attitudes about nature, wilderness, race and ethnicity, technology, mobility, and the city during an era of intense transformation that was often self-consciously referred to as “the machine age.” For a collector, on the other hand, despite the status of these cards as historical artifacts, they may awaken nostalgia for a lost world evoked by colorized images whose details were exaggerated in the first place.

Although postcards might seem simple objects, they have served relatively complex purposes. Acquiring a postcard has often verified one’s presence at a tourist site or other location and conveyed virtual possession of that place when a visitor left with its miniature image in hand. Although some tourists have collected postcards as personal souvenirs, others have mailed them to friends and relatives while en route or after returning from a trip. Postcards also facilitated communication with acquaintances in nearby towns during the early twentieth century, when postage was only a penny (half that of a letter), mail was delivered twice daily and in some places even more frequently, and long-distance telephone service was prohibitively expensive. Recipients often discarded such functional cards but sometimes kept them for their images. Cards sent by traveling friends or relatives have often played more problematic roles. Such cards might have aroused envy if recipients had not personally visited the pictured sites, or they might have evoked expanded horizons by suggesting places for future visits. A postcard acquired while traveling and saved for years or decades by the purchaser might later have become a key to reviving personal memories. In some cases, a card’s conventionalized image might have served as the only reminder that a person had actually visited a particular place at some point in the past. Finally, for a present-day observer, a collection of stylized postcards from the 1930s and ’40s might provoke nostalgia or even suggest an idealized alternate reality or retro-utopia, an enticingly close parallel world.

When considering linen postcards in the context of their own time, we must assume that people who purchased, sent, or received them regarded these views of the American scene as approximations of reality. Any doubt in the phrase “they do say it’s real” referred more to the astonishing saguaro cactuses themselves than to the degree of fabrication involved in their portrayal on the postcard. Over the years enough people have marked an X on the window of a hotel or motel room as an indication of where they stayed to suggest acceptance of postcard images as shorthand for reality. According to Caren Kaplan, an anthropologist of travel, tourists are offering “proof of the authentic” and engaging in “a technology of documenting the ‘real’” when they select and write postcards.3 Following her hint, this study traces the development of vibrantly colorful linen postcards as a technology of representation. Between 1931 and the early 1950s, Teich & Co. published about 45,000 unique individual views of the United States in the linen format. Imitators and competitors such as Tichnor Brothers and Colourpicture in Boston, Metrocraft in Everett, Massachusetts, and a score of smaller printers brought the total number of unique linen views to more than 100,000. A conservative estimate suggests Teich and other companies printed in total over a billion linen cards in twenty-five years.4 The presence of these cards in everyday life was significant even if people often discarded them, and their commercial success indicates popular acceptance of their collective portrait of America.

Because linen cards did not emerge in a vacuum, this book opens with a history of picture postcards beginning with the late nineteenth century. Various earlier types of view cards ranged from individual photographic prints and mechanically printed black-and-white halftone cards to lithographic cards printed in up to sixteen colors. Curt Teich, a German immigrant printer, pioneered the use of offset color lithography for postcards and in 1931 introduced the linen variety, which quickly triumphed over other types in the United States. The linen postcard’s unique aesthetic derived as much from new printing methods and economic constraints as from any intention of creating an innovative visual style. After reviewing the linen production process, one cannot help marveling that inexpensive, mass-produced artifacts designed, printed, and shipped out by the thousands from Chicago could project an aura of the local and the particular.

Tension between the generic and the specific becomes obvious when one examines the iconography of the American scene conveyed by Teich and other postcard printers. Natural and rural views, whether of eastern farms and pastures, the Appalachian and Great Smoky Mountains, the desert Southwest, the Rockies, or rugged western scenery, privileged viewers as masters of all they surveyed, sharing a democratic abundance indicated even by the very intensity of the colors in which landscapes were represented. Somewhat indebted to nineteenth-century painting styles of the Hudson River School and more obviously to western paintings by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, the makers of natural views in linen often drew directly from archives of earlier landscape photographers, as when Teich based cards on images originally distributed by William Henry Jackson or H. H. Bennett. Linen view cards recapitulated and further popularized long-standing notions of picturesque nature and wilderness.

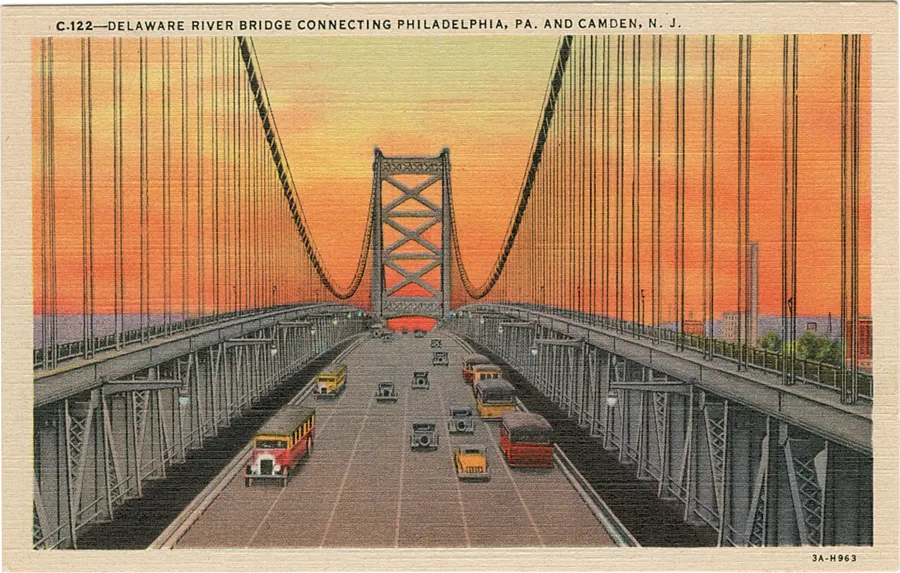

Despite relying on earlier romantic vistas, natural scenes often included modern highways offering easy access by automobile. Emphasizing mastery over nature, the iconography of linen postcards glorified the technology of bridges, dams, and factories. Towns and cities appeared in bird’s-eye and skyline views, often at night, when electric light’s artificial brilliance emphasized outlines of buildings and window grids. Street scenes portrayed an array of commercial signs, with crowds reflecting an upbeat urban tempo (fig. 1.3). Views of landmarks heralded each locale as unique even though a common visual style conveyed a sense of the generic. Cityscape postcards often echoed the grand-style urban photography of the late nineteenth century, but on occasion they suggested parallels with Berenice Abbott and other contemporary documentary photographers. The extravagant formal qualities of linen cards were especially flattering to the stylized architecture of world’s fairs, whose popularity indicated wide faith in technological modernity during the Depression’s hard times.

FIG. 1.3. “Third Street Looking West, Jamestown, N.Y.,” Teich 9A-H1881, 1939

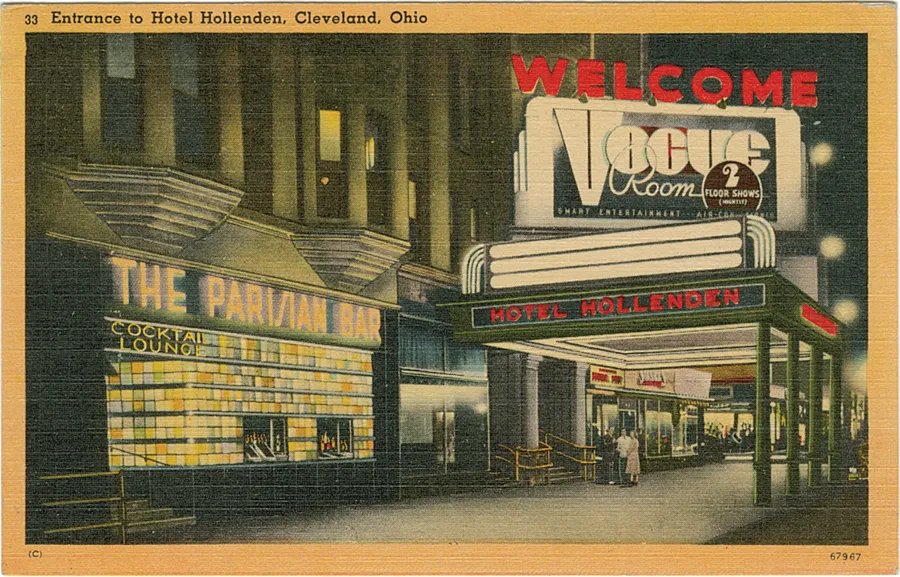

Linen postcards were often used to promote individual roadside attractions, hotels, motels, and restaurants. Such commercial images emphasized the cosmopolitan styles of Art Deco and streamlining (fig. 1.4). The colorful linen process heightened their effects and suggested that machine-age technologies afforded a supremely malleable reality. The production of interior views of hotel lobbies, cocktail lounges, and other commercial establishments frequently relied on paint chips and upholstery swatches submitted by clients to authenticate patterns and colors. Cards with interior views often seem the most realistic of linens owing to their meticulous detail. Their overly fabricated realism, characterized by the painter John Baeder as having a “messed-with” quality,5 promised access for everyone to exclusive fantasy realms.

FIG. 1.4. “Entrance to Hotel Hollenden, Cleveland, Ohio,” Tichnor 67967, n.d.

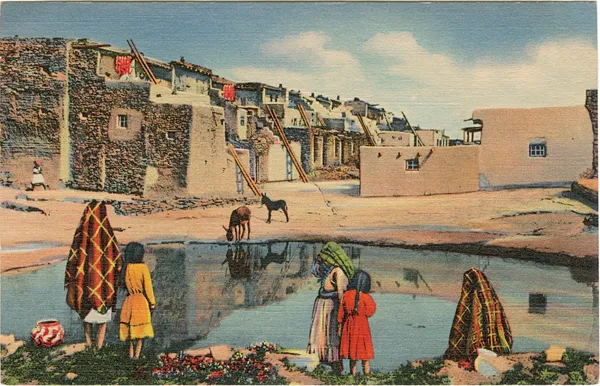

Although the American scene of linen postcards belonged mostly to middle-class whites of western European origin, members of ethnic and racial minorities, immigrants, and working-class men and women also purchased, sent, and saved them. While the typical perspective of oversight and mastery may have promised marginalized consumers a degree of inclusion, a significant number of linen cards objectified and romanticized the nation’s most visible minorities. African Americans in the South, Native Americans in the Southwest and Southeast, Mexican Americans in Texas and California, inhabitants of various urban Chinatowns, and even white Appalachian mountaineers were represented in stereotypical costumes and activities. They often appeared so passive and mute as to be naturalized into unchanging landscapes (fig. 1.5). Such representations of minorities counteracted the very modernity often celebrated by linen view cards and in doing so suggested the survival of static pockets of unchanging tradition.

FIG. 1.5. “Pueblo of Acoma, the Sky City, South of Laguna, N.M.,” Teich 6A-H2777, 1936

My approach mostly takes postcards of the 1930s and ’40s at face value as representations of an alternate world somewhat congruent with realities perceived by their consumers. Behind the scenes, however, clients, sales agents, artists, and printers collaborated in manipulating the black-and-white photographs to which the linen colorizing process was applied. Those Americans who accepted the authenticity of postcard views would have been astonished by what was added, subtracted, shifted, or altered in moving from a glossy photograph through an airbrushed photo and hand-painted watercolor mockup to the five printing plates required for production. Detailed job files for thousands of linen cards printed by Teich reveal manipulations ranging from basic cleaning up or simplifying of images to major transformations with definite ideological intent. Although Teich’s photographers and artists were participating in a commercial venture, many took pride in their work as art. The aesthetic they collectively fostered accurately portrays aspects of its era for the very reason that the verisimilitude they took pains to capture often dissolves when closely exa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Frontispiece

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. “They Do Say It’s Real”: An Introduction to Linen Postcards

- 2. Curt Teich and the Early History of Postcards

- 3. The Linen Postcard: Innovation and Aesthetics

- 4. Landscapes in Linen Postcards: A National Imaginary

- Portfolio I: Landscapes

- 5. Cityscapes in Linen Postcards: Images of Modernity

- Portfolio II: Cityscapes

- 6. From a Rearview Mirror: Contemporary Reflections

- Notes

- Illustration Credits

- Index