- 217 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

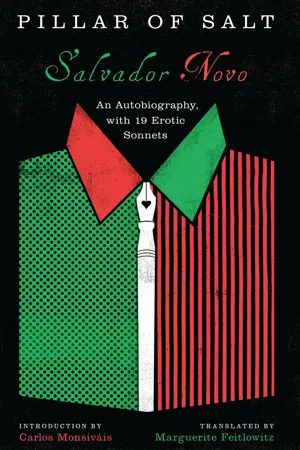

About this book

The renowned writer describes coming of age during the violent Mexican Revolution and living as an openly homosexual man in a brutally machista society.

Salvador Novo (1904–1974) was a provocative and prolific cultural presence in Mexico City through much of the twentieth century. With his friend and fellow poet Xavier Villaurrutia, he cofounded Ulises and Contemporáneos, landmark avant-garde journals of the late 1920s and 1930s. At once "outsider" and "insider," Novo held high posts at the Ministries of Culture and Public Education and wrote volumes about Mexican history, politics, literature, and culture. The author of numerous collections of poems, including XX poemas, Nuevo amor, Espejo, Dueño mío, and Poesía 1915–1955, Novo is also considered one of the finest, most original prose stylists of his generation.

Pillar of Salt is Novo's incomparable memoir of growing up during and after the Mexican Revolution; shuttling north to escape the Zapatistas, only to see his uncle murdered at home by the troops of Pancho Villa; and his initiations into literature and love with colorful, poignant, complicated men of usually mutually exclusive social classes. Pillar of Salt portrays the codes, intrigues, and dynamics of what, decades later, would be called "a gay ghetto." But in Novo's Mexico City, there was no name for this parallel universe, as full of fear as it was canny and vibrant. Novo's memoir plumbs the intricate subtleties of this world with startling frankness, sensitivity, and potential for hilarity. Also included in this volume are nineteen erotic sonnets, one of which was long thought to have been lost.

Salvador Novo (1904–1974) was a provocative and prolific cultural presence in Mexico City through much of the twentieth century. With his friend and fellow poet Xavier Villaurrutia, he cofounded Ulises and Contemporáneos, landmark avant-garde journals of the late 1920s and 1930s. At once "outsider" and "insider," Novo held high posts at the Ministries of Culture and Public Education and wrote volumes about Mexican history, politics, literature, and culture. The author of numerous collections of poems, including XX poemas, Nuevo amor, Espejo, Dueño mío, and Poesía 1915–1955, Novo is also considered one of the finest, most original prose stylists of his generation.

Pillar of Salt is Novo's incomparable memoir of growing up during and after the Mexican Revolution; shuttling north to escape the Zapatistas, only to see his uncle murdered at home by the troops of Pancho Villa; and his initiations into literature and love with colorful, poignant, complicated men of usually mutually exclusive social classes. Pillar of Salt portrays the codes, intrigues, and dynamics of what, decades later, would be called "a gay ghetto." But in Novo's Mexico City, there was no name for this parallel universe, as full of fear as it was canny and vibrant. Novo's memoir plumbs the intricate subtleties of this world with startling frankness, sensitivity, and potential for hilarity. Also included in this volume are nineteen erotic sonnets, one of which was long thought to have been lost.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pillar of Salt by Salvador Novo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Pillar of Salt

SALVADOR NOVO

MY EARLIEST CHILDHOOD MEMORIES appear as fragments, disjointed, with no continuity. Tardy and injurious attempts at psychoanalysis have salvaged from among them recollections of my most primitive stages of libidinal development, others that were lodged with especial strength in my memory, and some my doctor helped me recognize as particularly significant. Having spent my life in the company of a mother barely fifteen years my elder, my normal development stunted by an oedipal complex I am too cowardly to fully confront, I have made occasional anxious efforts to reconstruct with greater clarity the circumstances of my birth and youngest years. And so I learned that my father, a Galician, was thirty when he married the cheerful, robust, provincial brunette of fourteen or fifteen who was my mother, the youngest of four daughters in a family of nine children in Zacatecas. The head of that household blithely went through the family’s money, and when he died at the beginning of the last century, he left my grandmother, who had an admirable talent for getting along, the problem of raising and educating their numerous brood.

The eldest of the four sisters, Virginia, married a North American who lost no time in leaving Zacatecas and establishing himself in Mexico City, where their four children were born: Lilly, Edna, Fred, and Ruth, who is exactly my age. My mother likes to recall that, at the time, she herself was closer to her brothers than to her sisters, was tomboyish and quarrelsome, intuitive and clever in school. When my father, after having lived in Havana, settled in Zacatecas and fell in love with her, the clever girl saw a swift marriage not so much as the culmination of real affection on her part, but rather as her opportunity to escape the confining life she had at home. The wedding took place quickly, as soon as my mother’s family, whose older boys had started working for the railroad, moved to Mexico City, where the infatuated Spaniard followed. My parents took their honeymoon in Aguascalientes; but they returned to the capital for my birth, which occurred on July 30, 1904.

I have also learned that I was alarmingly late in learning to pronounce the letter r. As for other childhood traits, I have heard myself described as indiscreet (I would tell certain visitors what my family whispered about them, or reveal the nicknames we had for them among ourselves), and prone to fix, with my own hand, anything I considered to be flawed. It is also said that when they took me visiting, I would run to inspect the bedsheets, and often pronounce them ugly or soiled; and once, my aunt Maria surprised me in the living room of her house, where I was painting mustaches and stripes on the portraits in the family album. When she cried out, I looked up and, with all tranquillity, pointed to the portraits on the walls and explained, “I still have to finish all those.”

Maybe it is natural in children, but in my case I think it necessary to emphasize that my father’s image disappears almost entirely from my childhood memories. I know he was slender, blond, with light-colored eyes, but I can barely remember any of his interests or activities. Later I have a much clearer recollection of his making things with his hands. I remember, as though it were a dream, that he made a plaster lamp for the bedroom that gave off a soft light. His modus vivendi, his versatility, which later I also observed with greater precision, led him in my youngest years to try his fortune by opening a butcher shop, for whose inauguration, replete with fireworks and a party, we made paper chains of pink and china blue; or by taking part of the house and turning it into a tailor’s studio—no doubt to spring himself from his meat slicer’s job in a grocery store downtown.

My mother’s image, on the other hand, has always been clear, full, and vigorous. I would go out with her in the early evening to visit my grandmother, or a couple with two children my age, or simply to take a walk, stopping on our way to buy treats for dinner. I would go out with her in the morning, after she returned freshly coiffed from her beauty shop, and take a horse-drawn carriage to the consulting rooms of Dr. Porfirio Parra, who tended me for illnesses I no longer remember.

It was always my mother who came for me at the Herbert Spencer kindergarten. Of that establishment I only remember two things: once they made us plant orange seeds and on another occasion they selected me to sing at an important school festival to be held at the Teatro Arbeu, with Don Justo Sierra, a government minister, in attendance. Sowing the orange seed in the garden of the kindergarten greatly intrigued me. For years afterward, I dreamed of returning to the spot and gazing at the tree that had been born, miraculously, from that seed. As for the festival, I remember clearly that the song they had me sing demanded I be dressed as a Neapolitan organ-grinder, with blue velvet shorts, a cap, and the instrument strapped to my chest; upon taking the stage, I was to gesture leftward to the wings, and sing:

I come from those mountains

beyond the sea.

That is all I remember, other than the melody of those lines, which suddenly rises up from the reservoir of my five- or six-year-old memory, which has also conserved the blurry image of Minister Sierra in the act of giving out diplomas, and how some photographers made me climb up onto the lid of a sky-lit toilet in the Teatro Arbeu to pose me for pictures that came out in El Mundo Ilustrado—in whose archives the photograph must still exist.

On that occasion, as on practically every other day, my mother dressed me with fanatical attention. She adored the curls she combed around my forehead; she powdered my face; she made me purse my lips so my mouth would stay small; and, with the same inhibiting objective, she made me always wear shoes that pinched my natural development. A photograph from that time, which I still have, immediately brings to life the tortured recollection of the day I was taken to the studio, on foot, wearing shoes that hurt me horrendously.

My uncles loved me in the same admiring way. Proud of my beauty, they would take me out strolling with them on Sundays. My uncle Paulino, the eldest, would pick me up and buy me sweets and balloons in the Alameda. I also remember that one of those Sunday outings must have coincided with the opening of the Amphitheater in Juárez, because the crowds got in the way of our usual walk.

This is the period of my first sexual memories; though discontinuous and disjointed, they are recounted here in close proximity. We had at home a little servant, named Samuel, with whom I used to play. When I played alone, making altars with my blocks and empty cookie boxes, I didn’t need anything or anyone else. But when I played with that boy, I wanted us to pretend to be mother and son, and he then would have to suck on my right breast with his hard lips and erect tongue. This caress filled me with a strange pleasure, which I only recaptured many years later, when in a moment of exquisite surrender, I recalled that first and perhaps definitive experience, which may have been the original trauma that explains the formation of my adult libidinal predilections.

In the house next door lived some North American kids, one of whom, somewhat older than I, was occasionally my playmate. I don’t remember if we always did this, but one time we hid under his dining room table, covered by the tablecloth, and he, opening his fly, invited me to touch what he called his plantain. And so I did, until his mother, who lay ill in the next room, shouted out to us. They spoke in English, which I didn’t understand; but a strange intuition made me understand that the boy was defending himself to his mother against the accusation of a sister who had come in on us unexpectedly. What had happened, he explained, was that he’d been telling me how the previous Sunday they had gone to Vallejo—this word I remember with total clarity—and bought plantains.

The boy’s sister must have been as sexually precocious and aggressive as he was, because another time, at my house, she came into the bathroom, lifted her skirt, and made me lick her sex. I remember the taste, which was salty, and her clitoris, which looked like a tiny nipple. Another curious heterosexual experience occurred with my cousin R. My uncle Manuel had just been awarded his medical degree, and my cousin and I would play doctor and nurse in his office, which he had set up in my grandmother’s house. R. was the nurse, and I had to give her an enema, but with my penis in the “normal” opening, which she presented to me naked. I shied away from the operation, explaining that we should try her anus instead (and here I lied through my teeth), because at school they had told me that the other way, worms would come out. The experiment was never in any way consummated, needless to say, neither in the manner she seemed to want, nor in that which I said I preferred.

I showed signs of having a good memory, and my mother, who read a lot of poetry, made me learn “recitations” even before I entered elementary school. I knew “Guns and Dolls,” which I declaimed with studied gestures, and delighted in the whole anthology from which it came. The “Cantor del Hogar”1 was then a prominent figure. They said his poems had been translated into many languages, and were much admired for the references to his unfortunate private life, the details of which I managed to overhear. And so, on the day of his funeral, when his sumptuous cortège proceeded down Calle Guerrero, we all leaned out of the window to watch it go by, and at home we talked a great deal about that poet.

I don’t know why, but upon entering the official elementary school near where we lived, instead of starting in the first grade like everyone else, I was immediately placed in the third, with boys who, naturally, were older. I suppose the entrance exam indicated that I knew more than was usual, and thus justified that they advance me according, let’s say, to my mental age. My sudden immersion in that dirty classroom, with those impoverished boys, was extremely unpleasant. The smell and touch of a certain green ink—alizarina, I think it was called—found in the inkwells of every desk, is associated in my memory with anguished afternoons spent practicing my clumsy penmanship, and with the recollection of an incident that was destined to seed, or nourish, my guilty inferiority complex. It happened that one of the boys, maybe even my gringuito of a next-door neighbor, gave me a mildly pornographic sepia print of a naked woman. An older boy, who caught me looking at it between the pages of a book, seized the print and threatened to denounce me to the professor unless, every afternoon, I brought him all the sweets he wanted. Alarmed and submissive, I accepted the blackmail and for many days complied with his conditions. After our midday meal, I would ask my father for money and, on the way to school, I would buy those sweets, which I saw as my own inexorable complicity in the secret of my first moral transgressions.

Two fragmentary memories allow me to date to 1911—when I was seven years old—the period when my father left for the northern region of the republic, where we soon joined him, to seek our fortune, or obliged by circumstances, or impelled by a spirit of adventure that I certainly did not inherit. There is the memory of the furor that marked Madero’s2 entry into Mexico City, a nightmare midnight when I awoke in my parents’ arms as the doors rattled, and people threw themselves into the streets beseeching the heavens; and there is the impression of having read, as an enormous headline in an Extra edition of the Imparcial, the words PEACE, PEACE, PEACE, referring to the end of the revolutionary rebellions in the north. Very soon afterward, my mother and I would board the train for Chihuahua, to join my father, whose brothers were storekeepers there.

The one who lived in the city of Chihuahua, the one my father had gone to join, was named José; he was older than my father, less blond, and had a large mustache. They had to have been together in Zacatecas, because Uncle José had not forgotten his unrequited love for María, my mother’s older sister. Even I, who adored her, called her “My sister María.” At the train station in Mexico City, as she kissed me one last time, María offered to send the supplements to the Sunday papers to cheer me up; and they always arrived promptly, with her letters, at the grocery store run by my father and Uncle José, in whose back rooms, my mother and I, torn away from her family, were slow to adapt to that rather provisional, pioneering life. The difficulties clearly challenged and inspired my father to keep struggling, even without my mother’s cooperation, which in any case he couldn’t have hoped for, since she plainly didn’t love him and had no interest in helping him forge ahead to build their family fortune. My mother’s attitude was one of hard, silent reproach for a man from whom she had expected that, in payment for their notorious difference in age, he would have showered her with comfort and riches, without her giving more than her unresigned tolerance. In the face of my father’s delicate health—doubtless owing to which I am an only child—my mother dug in to life in her early twenties with a sullen strength, with a will to survive made evident by her vigor. Uprooted from the affection of her mother and siblings, far from turning her attention to my father, she invested it fully, tumultuously in me.

For my part, I, too, found in her caresses a refuge against our displacement and separation from my loving aunts and uncles in Mexico City, which from then on was imbued with the symbolism of an objective; we were in exile, unjustly and provisionally, on a peripatetic adventure in a hostile world to which my mother and I declined to adapt and which we could not accept as our place of residence. From Uncle José’s store we moved to downtown Chihuahua, and I began studying at the school annexed to the Institute, of which I remember only isolated visual details and my friendship with the Valderrama boys—Salvador, Ángel, and Sergio. In the mornings, the cold was horrible. In Return Ticket, I believe I sketched the fragment of an impression of that winter, when water froze in the faucets and, one day, on the way to school I saw a dead dog crystallized on the sidewalk.

My memories now are clearer or will become so in Jiménez, Chihuahua. My father had evidently secured a good position with the Casa Russek, a large store, and soon we were settled in that little village. The house we lived in was enormous. It gave onto three streets. Two or three large rooms separated by a wide hallway faced one street; forming a right angle with other rooms, they also looked out on another street. Yet another angle was formed by the big dining room, which connected to a different passageway leading to the kitchen and continuing out to the yard, whose gates opened to the street that ran parallel to the one in the front of the house. All of the bedrooms gave onto the central patio, which had a little well near the dining room, and a rustic little garden that flourished without tending in that agreeable and fecund climate. My father installed a swing for me in the center of that garden; and when I wasn’t playing with the yard animals—the lambs, the hogs, and the hens for which my mother began to show some condescending affection as our placid life fattened her up—I enjoyed long hours on that swing. But this last move upset my discipline at school. In Chihuahua I had repeated the third grade, but I’m sure I didn’t finish it, given that they registered me for the same grade in the Jiménez public school. I’m not very clear about the order of my educational experiences during that time; which is to say, I don’t know if I was in the official school before I studied in the little private one across the street from our house, or after; nor do I have a chronological sense of those two schools with respect to the teacher who came to tutor me every afternoon at home, closing the doors to the dining room where we had my lessons, and who may have enhanced my progress at other schools or weakened it, I don’t know, owing to my inhibitions surrounding these memories. It’s possible that, owing to the Revolution, then at its peak, the official schools were frequently closed, and private ones were temporarily taking children in. In any case, my recollections are clear with respect to each of these three separate pedagogical experiences. The little private school was the cottage industry of two unmarried sisters, the Señoritas Rentería, one of whom would eventually become one of Pancho Villa’s widows. There they mostly taught me religion and drawing. I found it soothing to draw, again and again, a cross adorned with forget-me-nots. As for the teacher who came to our house, he had me read while he watched. One afternoon, he decided to caress me, and he placed his hand on my fly. With great delicacy, he asked, What do you call this? Anus, I told him, because that was the name my mother had taught me for penis. Since he didn’t seem to agree with that alteration in anatomical nomenclature, that night I tried to verify it with my mother, referring to my tutor’s lesson. It is quite possible that this discrepancy provoked his dismissal.

The official school was a disagreeable reproduction of the one in Mexico City. Populated by poor kids, many of whom had no shoes, its director was a solemn and squalid teacher who suffered from a bad complexion. Only a few of the boys were sons of families with whom my parents had begun to form friendships in the village: the Galvaldóns, the three Botello boys, two older than me and one my own age, all very pretty, the youngest of whom was my friend in class and my playmate at home. Although at school I abstained from mingling with the others, I could not escape their whisperings. That is how I learned that the beautiful Botellos had been the sexual victims of someone somewhere who had lured them into a car—cochado3 was the verb they used. From that very instant, I developed an interest in cultivating the friendship with the boy who was in my group. An investigative interest, much colored by the need to affirm and assure the validity of my own narcissism. As a game or a joke, or out of instinct, the boys went around kissing the Botellos, as they laughingly referred to them. But they stayed away from me. Not because I didn’t want the caresses of any of those boys, all of whom I found ugly. What I needed was proof of my own beauty, more objective than the simple adoration I was accustomed to at home; an assurance that the public attention, the admiration, expressed in the caresses of those boys at school, would have offered. But the assurance didn’t present itself; and from then on, I was impelled toward exhibitionism and a compensating mythomania. So I would bring that Botello boy home, and after running around for a while, I would make him sit with me on the swing, where I would draw out his statistical secrets. How many times had they kissed him that day at school? I don’t know if we weren’t both lying when we each confessed to two or three times. Then we would kiss, and perhaps, truly, it was the only kiss, out of so many we boasted of, that either of us had been happy to receive.

The domestic staffat home was composed of a huge family of a mother, two or three daughters, and a typical invert of a son, whom they openly called “Juan the faggot.” With his straw hat always on his head, he happily carried out the feminine household tasks, helped his mother in the kitchen, did the washing, ran errands, fetched me at school. But I kept him at a distance, I don’t know if owing to my parents’ vigilance, or to my own repugnance and hostility, but I constantly made him the victim of mean tricks. I remember once I caught a fly, called him into the dining room, and when I had him within reach, opened my fist, and shoved the fly into his mouth, rubbing it against his teeth, as triumphant as I was irritated by his docile resignation to my cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Frontispiece

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Pillar of Salt

- “This flower of fourteen petals”

- Sonnets

- Notes

- Index